Campaign finance laws and the Homeless Industrial Complex

January 12, 2017

Seattle perceives itself as a national leader in the effort to get money out of politics. Initiative 122, approved by voters in 2015, tried to attack the problem in two ways. First, it created a “democracy voucher” program that would give every adult citizen four $25 vouchers to give to the candidate(s) of their choice. Second, it lowered the contribution limit for all candidates. Third, it forbade any companies doing over $250K in business with the city (or their owners) in the two years previous to the election from contributing anything. All these rules and regulations are enforce by the Seattle Ethics and Elections Commission (or SEEC) of whom I have written before.

I’m going to take a look at how that last part of I-122 has been working out, particularly as it regards homeless services contractors. But first, some background on why campaign donations from contractors are a problem.

Last spring, after Seattle mayor Ed Murray ran into trouble with sex abuse allegations, I scanned his list of his re-election campaign donors and was surprised to find the name of a friend of mine who I knew didn’t care for Mayor Murray at all. She’d had contact with him often while working for a civic improvement organization, and she’d told me stories of what a rude and thoughtless person he was. Given this, it struck me as odd that she would have given Murray money for his campaign, so I asked her why she was giving him money. “Because at the time I made the donation I thought he was going to win, just like everyone else did,” she replied, “and you can’t get anywhere at City Hall unless you chip in for politicians’ campaigns.”

“You mean you can’t get them to give your group what it wants ?” I asked.

“No,” she said. “I mean you can’t even get a meeting to tell them what we need from the City.”

My friend was talking about pay-to-play. Pay-to-play has different meanings in different contexts. In sports and gambling it means one thing, but in politics it refers to a system…

–akin to payola in the music industry, by which one pays (or must pay) money to become a player. Typically, the payer (an individual, business, or organization) makes campaign contributions to public officials, party officials, or parties themselves, and receives political or pecuniary benefit such as no-bid government contracts, influence over legislation, political appointments or nominations, special access or other favors. The contributions, less frequently, may be to nonprofit or institutional entities, or may take the form of some benefit to a third party, such as a family member of a governmental official. –Wikipedia

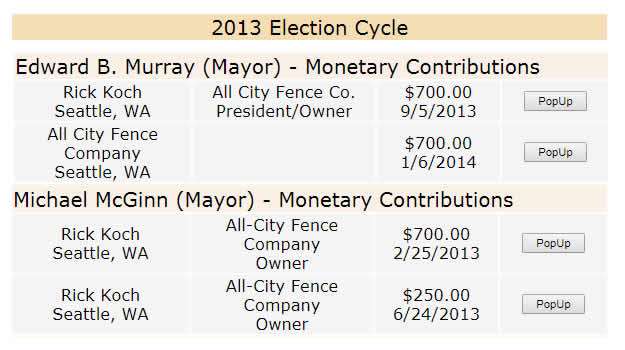

I’ve discussed pay-to-play on these pages before, in an investigative piece I did on how City contractors donated to Mayor Mike McGinn’s 2013 re-election campaign. [See The Friends of Mike McGinn]. However, when I wrote the McGinn piece, four years ago, I assumed that contractors who were donating to McGinn’s campaign were thanking him for services already rendered. At that time, I didn’t understand that the donations were the price of admission to the game. Now I do.

All City Fence: A case study

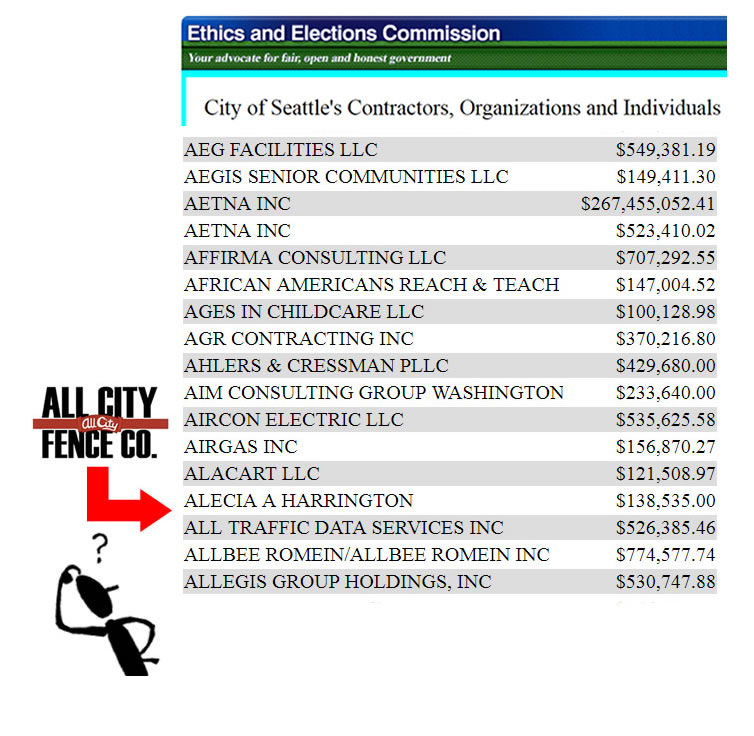

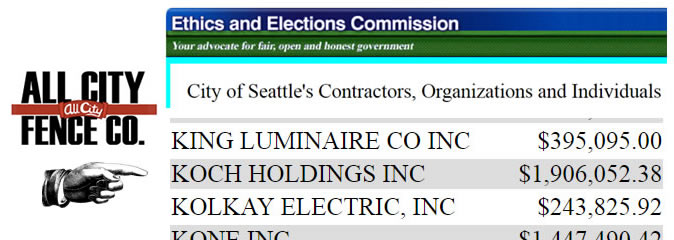

While researching Ed Murray’s donations and comparing them against the SEEC’s list of contractors forbidden from donating under the new I-122 regulations, I came across another thing that puzzled me. I was surprised to see that a contractor I was familiar with, All City Fence, was not on that list. All City Fence supplies much of the fencing that the Seattle Department of Transportation uses to secure the area around illegal homeless camps they remove, and there are miles of such fences around town, so I reckoned they must have some juicy contracts, and when I looked into it, it turns out I was right. All City did nearly $2 million worth of business with Seattle in the last two years. So why aren’t they on the list?

Well, they are on the list, actually. Just under a different name. When I told my friend Doug about the All City Fence mystery, he did an owner search on All City and found out that it also goes by Koch Holdings, Inc., named for All City’s owner Richard E. Koch. And that’s where we found it on the SEEC’s list:

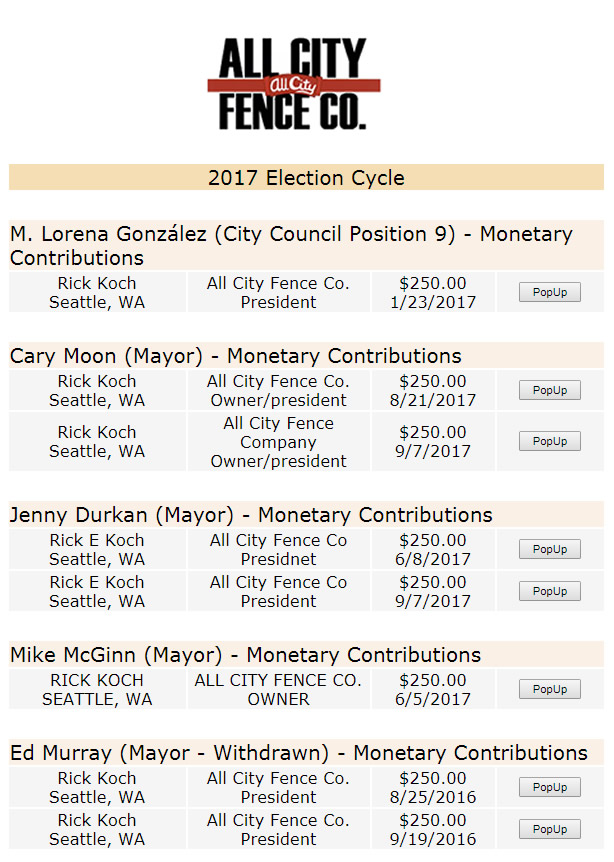

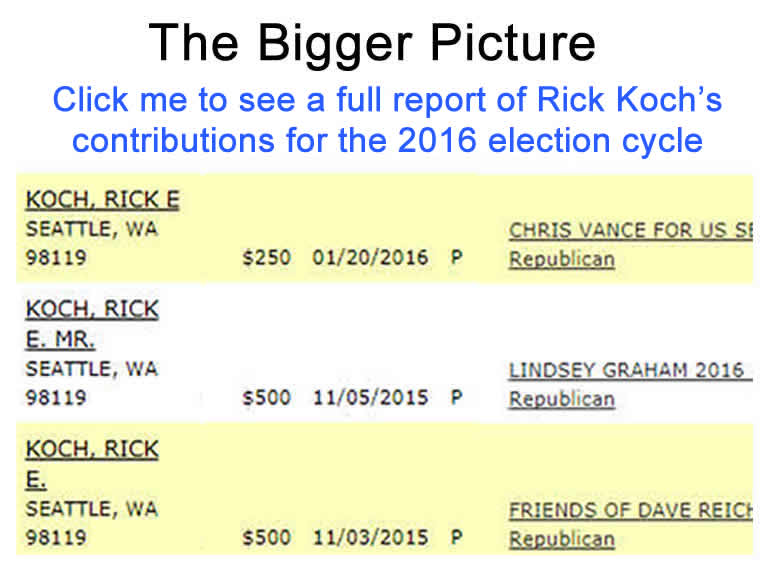

Doug and I then looked into Koch’s donation history. We wanted to know two things: Did Koch make donations to Seattle candidates, and if so, which ones? A search on “Rick Koch” or “All City Fence” on the SEEC’s contributor search tool returns a list of 36 contributions in the five elections since 2009, with eight of them in the 2017 elections (see below).

As I read the new law, all the candidates who received donations from Koch have violated it. However, that may turn on a single word with a particularly mushy interpretation. Seattle Municipal Code 2.04.601 states that:

No Mayor, City Council member or City Attorney or any candidate for any such position shall knowingly accept any contribution directly or indirectly from any entity or person who in the prior two years has earned or received more than $250,000, under a contractual relationship with the City.

–and of course the key word here is “knowingly.” Did these candidates know that Koch was on the banned list? Or didn’t they? And if they didn’t, did they have an excuse? The SEEC is the regulatory body that handles campaign finance violations. Accordingly, I have sent them notice of this violation. However, based on my experience with the SEEC, I’m not hopeful that anything will come of it, even if they do find that there were violations. Mr. Koch could come out ahead, actually, because if the candidates return his money, he’ll be getting a $2,000 payday, courtesy of me. In any case, I don’t believe the violations are the real story here. The real story is who Mr. Koch is giving his money to. And why. As we proceed, please remember that the pay-to-play story is not unique to one company doing business with the City. Or even one group of companies. It’s pervasive.

Habitual Donors

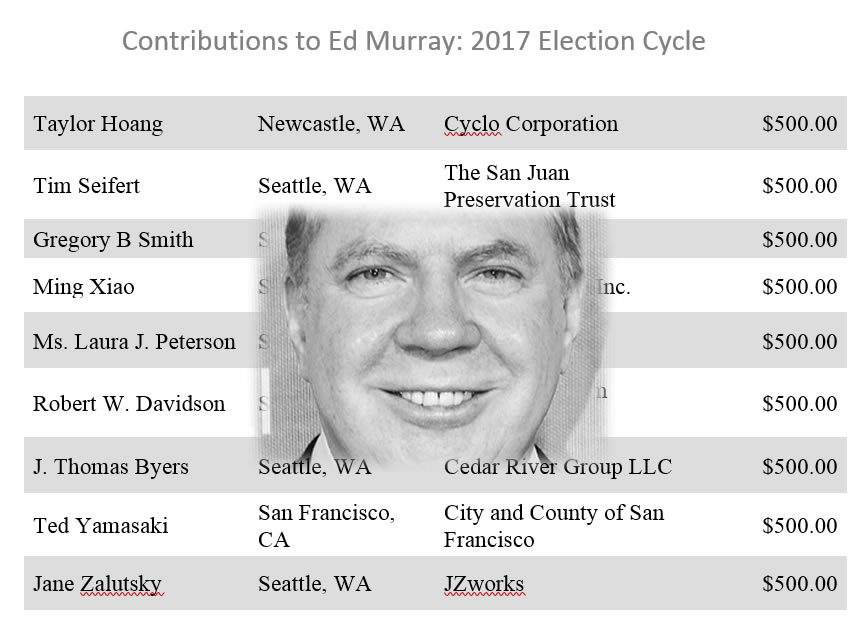

In the mayor’s race, Mr. Koch gave money to four candidates who had declared in the primary: Ed Murray, Mike McGinn, Cary Moon, and Jenny Durkan. Koch donated to both candidates who made a second round of donations to candidates who made it into the general election as well: Moon and Durkan. Of the four mayoral candidates Koch gave money to, he gave three of them (Murray, Moon, and Durkan) the maximum of $500.

The first donation Koch made was to incumbent Mayor Ed Murray in August of 2016. That was at least six months before the primary season had begun. (See Appendix A for a list of Murray’s donations from all sources.) Why did Koch donate to Murray so long before the primary was underway? Probably because he figured that Murray was going to win, which was a reasonable assessment at that time, before the rape allegations came out against Murray. It’s understood by savvy donors that the best time to score brownie points with an incumbent candidate is as early in the campaign, when the candidate is building a war chest with which to intimidate challengers.

After Murray bowed out in the wake of the sex scandal, people were coming out of the woodwork to run for mayor. But that didn’t mean Koch couldn’t still take an educated guess at who would win. In early June, he sent money to Jenny Durkan, who was polling in first place at the time, and also former Mayor Mike McGinn, who, along with three or four others, was jockeying for second place. Then he sat back and waited for the primary vote.

On August 21st, three weeks after the primary, Koch gave a donation to the runner up, Cary Moon. One month later, on September 27, 2017, he topped up his donations to both finalists: Durkan and Moon. At that point he could relax in the knowledge that whoever won, he’d given them as much money as he could.

If you look at Koch’s donations over the years, you see a series of similarly calculated hedges. He doesn’t seem to care who wins elections, as long as he’s given money to whomever that turns out to be. This is his best guarantee that that person will remember him fondly any time the City needs to rent some fences.

Nice work if you can get it

Let’s take another look at just what Mr. Koch’s company does for the City. In this video, which I shot for another story, we see about a third of a mile of All City fencing that Seattle paid the company to put up along a stretch of road that had been attracting homeless camps and RVs:

In February 2017, the City began sponsoring a large homeless encampment called Camp Second Chance in this area, and that camp quickly became a magnet for tents and RVs in the general area. For months the City allowed the situation to worsen, but after neighbor complaints escalated, the City finally took action. After giving the required notice to the squatters, the City brought in special “multidisciplinary teams” to tow off the RVs and pack up the tents. A temporary fence was then installed around the perimeter to keep the squatters from coming back. Nearly four months later, the fence is still there, at a cost to the city of tens of thousands of dollars, and counting.

The area under the Spokane Street Viaduct has been cleared (or “swept”as it’s commonly referred to) at least twice. City crews working for the Department of Transportation (SDOT) will come in and clear a camp and then hire All City (and sometimes other contractors) to install a fence around the grounds. A month or so later, the fence will come down, and within weeks of that, the homeless campers will have moved right back in. SDOT will then repeat the process with another sweep and another fence. And the fence companies will clean up. According to an online report, All City does roughly a quarter of its business with Seattle, and that number is likely to rise as Seattle needs ever more homeless camp fences. The document below is a $2 million contract between SDOT and two fence companies: All City and a place out of Renton called On Site Security Services, LLC – for “emergency fencing” services around the bases of bridges around the city.

[Document is nine pages. Move the mouse over the document and use the up and down arrows to scroll through them.]

SDOT Emergency Fence ContractsHomeless services and campaign donations:

What’s the connection?

What does the mayor’s campaign have to do with the City contracting for fences? Nothing, formally. The mayor doesn’t decide who gets a contract for fences. But the mayor does appoint the person who oversees the contracting process. For the past several years, that person has been Fred Podesta, director of Seattle’s Finance and Administrative Services Department. Podesta has a lot to do with the business of running Seattle, and as homeless services have developed into a huge, city-managed enterprise, that means Podesta has had to get deeply involved in decisions about who gets paid to do what.

Image credits: Seattle.gov (Ed Murray), Joe Mabel (Mike McGinn), Dennis Bratland (Jenny Durkan and Cary Moon)

Last summer I attended a meeting among Podesta, Seattle’s official Director of Homelessness George Scarola (aka the “homeless czar”) and a half dozen citizen activists who’d been urging the City to change its policy on homeless camps. Since 2015, the City has been paying non-profit housing providers to run an archipelago of “sanctioned” homeless camps around Seattle, at a rate of around $200,000 per camp, per year. When one of the activists argued that the City should stop paying for the camps, since they don’t move people into permanent housing, Podesta disagreed. He said he didn’t like the idea of using housing placements as the main criteria of whether the City should be supporting the camps. It had been his observation, he told the group, that there was just a certain kind of person who, for a certain period of their life, simply needed to live outside, and the camps were helping these people do that more safely.

While the group was meeting, a phone call came in to homeless czar Scarola. It was from Sharon Lee, director of the Low Income Housing Institute (LIHI). Like All City Fence, LIHI is the recipient of millions of dollars of City money. Like Richard Koch, Ms. Lee is a “habitual donor” and has given money to dozens of local politicians, including Podesta’s former boss, Ed Murray. (To see a full list of Lee’s donations, go here.) Lee is also a registered lobbyist and has close access to a number of of people at City Hall.

Above: A sample of the campaign donations Low Income Housing Director Sharon Lee has made recently. Below: (2015) Lee beams as Mayor Ed Murray signs a property tax levy bill raising hundreds of millions of dollars for LIHI and other homeless service groups. In addition to several apartment complexes, LIHI also runs an archipelago of “sanctioned” homeless camps around town. These camps have not been shown to move homeless people into permanent housing. Photo: Seattle.gov

In this article on trash clean-up at local homeless camps, we see another side of Facilities and Service manager Podesta’s involvement with the homeless services business. In the early spring of 2017, Podesta approved a plan for the city to pick up trash at some pop-up homeless camps around town. What the article doesn’t mention is that the trash pick-up work was to be done not by the City of Seattle but by a contractor: Waste Management, Inc. Waste Management, Inc. is another a habitual donor with deep roots at City Hall.

At a salary of $176,000 per year Fred Podesta is one of the highest paid employees at City Hall. Don’t expect him to quit any time soon, but if he does, there’s a good chance he’ll move to Waste Management, Inc. or some other company he’s worked with on City business. For more on campaign donations and the revolving door between Seattle and Waste Management see Appendix B.

“There are some people who just need to live outside for a certain period of their lives.” –So said Seattle’s Fred Podesta whose team was “working closely on homelessness response” according to former Mayor Ed Murray. Podesta oversees contracts with companies that manage or service homeless camps. The owners of these companies donate money to his bosses’ political campaigns.

Strange Bedfellows

Ed Murray and Jenny Durkan were both somewhat logical people for Rick Koch to be supporting with his donations during the campaign, since both of them were in favor of the continuing the policy of clearing and fencing homeless camps, from which Koch has been making so much of his money. But what about Candidate Cary Moon? She came out against the sweeps early in her campaign. And what about City Councilmember Mike O’Brien, another beneficiary of Koch donations? O’Brien has been a vociferous opponent of sweeps; he’s sponsored at least two pieces of legislation to stop them.

Koch gave O’Brien $1,400 over the last two election cycles.

If Moon had been elected mayor, she and Mike O’Brien would have directed the police to leave homeless camps where they were: no more homeless camp sweeping, no more fences. Wouldn’t that have been bad for Koch’s bottom line? Yes it would have. Koch may have been naive in his support for people like O’Brien and Moon. Or maybe he just knows something the rest of us don’t about the dynamics at City Hall. Koch doesn’t need to fear the existence of an anti-sweeps faction at City Hall, as long as it doesn’t come out permanently on top. And so far, it looks like it won’t. On November 15, the City Council, which most Council-watchers had assumed had an anti-sweeps majority, rejected, by a 6 to 3 vote, a measure to stop the sweeps by cutting funding for them. In the long run, Koch may benefit from the constant tug of war between the pro-sweep and anti-sweep forces at City Hall. Pulling down a fence around a camping spot only to put it up again a few weeks later when the winds change means more business for All City.

Here’s another curious thing about Koch’s relationship to Moon. Moon had framed herself not just as an anti-sweeps candidate but as an anti-corporate one. On September 13, six days after she received Koch’s donation, she tweeted that she would never take money from corporations because she didn’t want to let “private interests control the public domain.” Could she have been totally unaware that one of her donors, Koch Holdings, represented a multi-million dollar corporation that was making money from sweeping homeless camps? Either way, she didn’t send Mr. Koch’s money flying back to him.

Not-So-Strange Bedfellows

Richard Koch’s support for “progressive” Seattle candidates might lead you to believe he’s some kind of leftist, but such is not the case. He donates to other candidates as well, and the further farther away from Seattle you go, the less progressive his donations are. The online donations tracker CampaignMoney.com reports Koch donating nearly $19,000 to political campaigns in 2016, and although some of that went for Democrats, most of it went to individual Republicans, including the Washington State Republican Party and the Republican National Committee. In fact, overall, Koch donated nearly four times as much to Republicans and Republican causes as he did to Democrats or Democratic causes. From this, a reasonable person would infer that Koch is not a liberal Democrat – like the Seattle candidates he gives money to in local elections – but rather a moderate Republican:

Campaign Finance Reform: Harder than it looks

The contribution and spending limits of I-122 are a flop. The limits imposed on Democracy Voucher candidates would have worked if they’d been imposed permanently across the board, but because there was an escape hatch written to the law, the contribution caps have effectively floated back up to where they were before I-122. Another problem was enforcement. When I-122 was implemented, just one new FTE was added to the staff at Seattle Ethics and Elections Commission, along with some temporary workers, to handle the complicated new program. And there’s no one specially assigned to handle contractor contribution portion of the law. That means the contractor donations part of the program would have to depend on campaign workers to filter out and refuse these contributions. Campaign staff aren’t motivated to look for and refuse these donations because there’s no gain to them for doing that and little risk for them in not doing it. In 2017, there was just one complaint filed under the relevant statute (SMC 2.04.601) and that complaint was dismissed as “inadvertent or minor.” Had the complaint been upheld, it is unlikely the SEEC would have imposed more than a token penalty, and the story would not likely have made the news.

With SEEC staff not able to do the job, and campaign staff not wanting to do it, who else is there? Bloggers? Concerned citizens? Good luck with that.

These Waste Management Dumpsters were at the notorious Triangle homeless camp on Airport Way and Royal Brougham for several months from 2016 to 2017. I visited the camp in the spring of 2017 and observed that the Dumpsters were empty, even though there was trash all around them. When I asked a camp resident why, he told me that the camp started boycotting the Dumpsters after the City’s threatened to remove the camp. Although the Dumpsters weren’t used, the City still had to pay Waste Management to service them, at the cost to taxpayers of several thousand dollars a month. Photo: Richard Paddon

Few citizens even know about these new contribution laws, and, of those who do, fewer still are going to take the time to crosscheck a list of nearly 2,000 City contractors against donations looking for violations.

To give city contractors a heads-up on the new rule, the following language was added to all Consulting and Purchasing contracts for Request for Proposals and Invitation to Bids:

Campaign Contributions (Initiative Measure No. 122)

.

Elected officials and candidates are prohibited from accepting or soliciting campaign contributions from anyone having at least $250,000 in contracts with the City in the last two years or who has paid at least $5,000 in the last 12 months to lobby the City. Please see Initiative 122, or call the Ethics Director with questions.

–Perhaps that warning will get through to some contractors. It certainly wasn’t enough to keep Mr. Koch from donating, though. He signed a contract with that language in it, and he still broke the rule.

A Techno-Fix?

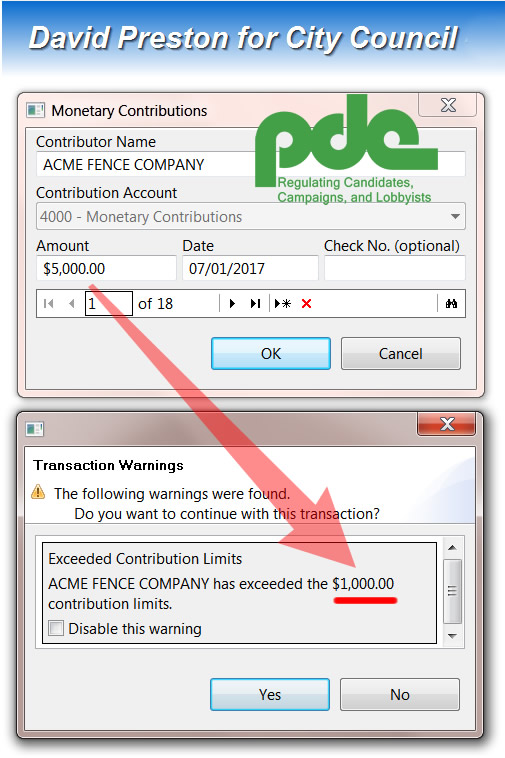

Campaign staff use a software program called ORCA to report all contributions to the SEEC. This software could be updated each election cycle with a list of $250K+ contractors to check donations against (for Seattle candidates only). This would be the easiest way to enforce the contractor contribution rule, but it will cost tens of thousands of dollars to implement and will add overhead to a complicated reporting process that’s become a burden for grassroots candidates.

The ORCA online campaign reporting tool (used by most Seattle campaigns) can flag all contributions that are over the limit. This feature could be enhanced to flag contributions from city contractors; however, that will require considerable additional programming time and contractors can still get around it if they’re determined to, by having others make contributions in their name.

Just fill out a form…

Alternately, all donors could be asked to submit a signed form (or check a box when making electronic donations) stating that they are not on the forbidden-to-donate list. That would be an effective way of educating people about the law, but it would be a drag not just on campaigns but on donors as well, and especially on the low-income, disenfranchised citizens whom I-122 was supposed to be getting more involved in the process. The electronic donation processing companies would have to be on board with it as well. –And all this to deter a handful of would-be cheaters? Cheaters who will likely find a way around the law in any case. Or will simply ignore it, knowing that the SEEC goes easy on the few scofflaws it does catch. It hardly seems worth it.

Non-profit contractors not affected by I-122

It’s important to remember that dozens of large organizations getting potfuls of money from Seattle are non-profit groups, like the one my friend who loathed Ed Murray (but felt she had to give him money anyway) worked for. Sharon Lee, the director of LIHI (whom we discussed above) did nearly $3.8 million in City business in the last two years and her $180,000+ salary comes out of that. But since LIHI is a non-profit Lee is not considered an “owner” of a “business, so she’s free to donate as much any other citizen.

I-122: On Shaky Ground

Finally, consider that I-122 itself might be illegal. The Supreme Court of the U.S. has ruled that political donations and advertising constitute “political speech” and are protected by the First Amendment, even when that speech is made by “corporate persons.” If a giant corporation like General Motors has the right to express speech by donating money to candidates, how can a guy like Richard Koch be denied the same right, simply because he has contracts with the City? The Democracy Voucher Program part of I-122 might also turn out to be illegal, since it contravenes Article 8, Section 7 of the Washington State Constitution, which states that tax revenues belonging to the city may not be taken and used to aid an individual (such as an individual politician):

SECTION 7 CREDIT NOT TO BE LOANED. No county, city, town or other municipal corporation shall hereafter give any money, or property, or loan its money, or credit to or in aid of any individual, association, company or corporation, except for the necessary support of the poor and infirm, or become directly or indirectly the owner of any stock in or bonds of any association, company or corporation.

That I-122 still stands at all might be due to the fact that no one has effectively challenged it in court.

Sunlight: The Best Disinfectant

The “Homeless Industrial Complex” has become a byword for Seattle’s failure to manage money wisely.* When people think of Homeless, Inc. they most often think of outfits like the Low Income Housing Institute, which gets millions of taxpayer dollars to warehouse people in “sanctioned” tent camps. But what about All City Fence, the company that puts fences around the illegal camp sites. And what about Waste Management, Inc., the contractor that gets paid for their Dumpsters to sit empty outside? And what about the handsomely paid Fred Podesta – the guy at City Hall who signs the contracts and says there there are some people who “just need to live outside”? Aren’t these entities just as much a part of Homeless, Inc. as anyone? They are all connected by a web of cushy jobs, political alliances, campaign donations, and maybe even kick-backs. Homeless, Inc. is the poster child for corporate influence and soft corruption in Seattle. It is the beast that I-122’s magic arrow was supposed to slay, but hasn’t.

If the “Honest Elections” folks behind I-122 thought that they were getting money out of politics by making a law to limit campaign contributions and then handing it off to an understaffed “ethics committee” they were being naive. The SEEC does a good job of tracking and reporting data, but it doesn’t go digging for violations. And that’s not the SEEC’s job anyway, it’s the media’s.

This is what one of the Low Income Housing Institute’s city-funded homeless camps looked like in early 2015. Conditions at the camp were so bad that LIHI eventually had to abandon the camp and petition Seattle Police Department to evict the campers. More on that story is here. Photo: David Preston

Speaking of the media…

Why isn’t the media on top of this? Maybe it’s more than they can handle. Or maybe it’s not worth the risk. A newspaper would need hundreds of column inches to do this justice, and in the process, they might turn the business community against them, costing them precious advertising revenue.

The Seattle Times gets it. Kind of. A Times piece published on October 7 examined charges of pay-to-play that were leveled by a candidate in the City Attorney’s race. That was a good start, but then, inexplicably the Times didn’t follow up and ask who else might be getting pay-to-play cash. In a recent article on new fencing planned around Seattle, the Times declined to name the companies involved or to explore their relationship to City Hall. (They also under-reported the amount of money by half: Seattle budgeted $2 million for homeless camp fencing, not $1 million). The Times has run dozens of stories on homelessness in the last five years, and in these stories, they’ve quoted staff from Homeless, Inc. players like LIHI and SHARE a number of times. But so far they’ve neglected to take a closer look at these groups’ inner workings or their relationships with local politicians.

If a nationally recognized paper like the Times can’t, or won’t, tell the story of soft corruption at City Hall, we certainly can’t expect a dinky little blog to do it. Or can we?

–by David Preston

Additional research: Doug

*Seattle’s 2018 budget is projected to be just over $6 billion, the eighth largest in the nation, even though we’re only twenty-first in terms of population. In 2015, we had the fourth highest spending per capita among larger cities in the U.S. according to Ballotpedia, and since then the number has risen. Seattle’s 2016 population was estimated at 750,000. Divide that number into a budget of $6 billion and you have a spending rate of $8,000 per Seattle citizen, up from $6,700 just two years earlier.

Appendix A

Seattle’s Ed Murray was popular throughout much of his administration; however, he was not well liked by those who worked closely with him. After sex abuse allegations came out early in 2017, Murray decided not to run for re-election. In the early primary season, Murray had already amassed a war chest of $361,000, much of it coming from em employees of companies doing business with the City. Click on the image below for an itemized list of all Murray’s donations.

Click on this image for a full report of May Ed Murray’s 2017 primary season contributions. Photo: Mat Hayward/Getty Images,

Appendix B

Waste Management, Inc. is another large City contractor agency ($110 million+ in the last two years) that has historically given donations to Seattle politicians. Before I-122, the company gave money to City campaigns under its own name.

The revolving door: Before becoming an executive at Waste Management, David Della served a term as a Seattle Councilmember and worked several high-level positions at City Hall where he would have been in a position to help Waste Management. Source: LinkedIn

I-122 has forbidden that, but the company still gives money to a PAC that funnels money to City candidates, and one of the company’s manager’s, David Della (who was formerly a Seattle councilmember himself) also donates. To see a complete list of Waste Management’s campaign donations, go here.

Waste Management, Inc. does hundreds of millions of dollars of business with the City and the company may want to show its gratitude by helping politicians with their campaigns. All of them. Here’s how Waste Management gets around Seattle’s I-122 campaign finance restrictions. Click to enlarge this image.

Do you like the Blog Quixotic? Do you like this story?

Please consider donating.

Thank you, Henry B.

Thank you, Cameron C.

Thank you, John R.

Awesome job

I hope you have a good trip. There is so much good riding in Spain, particularly dirt road riding. I’m planning some rides in Portugal next year so more posts then!