September 8, 2018 ~ The biggest gripe a citizen can have is that their government doesn’t listen to them, and that gripe has never been more on-point than when it comes to transients and drug addicts camping in Seattle parks and streets. Seattle residents have been urging City officials to take action on this problem for years. City Hall’s response has been sluggish at best, and when it does act, it makes things worse.

The logical response to people living in tents is to create more indoor shelter space and move people into that preparatory to finding them a permanent, indoor place to live. But Seattle’s response has been to merely “sweep” the worst camps from place to place and to set up a network of “sanctioned” (read: legal) camps that compete with the illegal ones. The sanctioned camps, dubbed “tiny house villages” by their fans, are a cash cow for the group that’s contracted to run them and a PR bonanza for the City. But they’re not getting people into permanent housing, and in the meantime, they’re hell on the neighborhoods.

Sanctioned camps were the brainchild of the non-profit organization that manages them: SHARE. After several years of sparring with the City over its “right” to set up homeless tent camps on public land, SHARE’s director Scott Morrow persuaded his friends on the City Council to stop fighting him and to start paying him instead. Morrow proposed to create a network of camps around town on public and private land. The City agreed in principle and in early 2015 they passed a law that would allow for such camps to be created, but there was still a catch. Camp neighbors and their lawyers were bound to put up a fight if the City tried to do things by the book. How could they get around existing land-use code and public process requirements to get these camps permitted?

On November 2, 2015 Mayor Ed Murray solved that problem by declaring a homeless “state of emergency.” Once homelessness was established as a permanent crisis, due process and other legal protections for citizens could be ignored. And they were.

But what will the neighbors say? In late 2015 Seattle Mayor Ed Murray declared homeless “state of emergency” clearing the path for Scott Morrow to build a network of “sanctioned” homeless camps around Seattle, unhindered by land-use codes or neighborhood resistance. [Click to enlarge this image.]

The sanctioned camp program began in 2015 with a small camp in Ballard of about 25 residents. Now there are eight. Each camp houses between 20 and 50 people who were formerly on the street, and the cost to run a camp ranges from $170,000 to $700,000, depending on which City official you talk to. Unfortunately, the Seattle Human Services Department (HSD), which oversees the program, doesn’t publish cost summaries or detailed data on whether the camps are moving residents into permanent housing

At their public meetings, HSD pitches sanctioned camps as a “temporary solution” until the city can raise enough money and fund more shelter beds and indoor programs. People are told they can expect a slight, two-year disruption in the neighborhood. But three years of experience with these camps has shown that once one goes in it can be there for long time. Possibly forever. And if something goes wrong, the neighborhood is stuck with it.

How does it work?

In March of 2015, the City of Seattle passed an ordinance changing city zoning such that non-profit groups could apply to create and manage homeless camps (called transitional housing in the ordinance) on City-owned or private, church-owned land. In the sanctioned camp model, which takes the idea one step further, qualified non-profits can contract with HSD to operate these camps. Under the contract (see here and here for examples), the City pays for much of the camp’s operating expenses. The “tiny houses” in these camps don’t have to meet housing code requirements because they are smaller than the 120 square foot minimum for dwellings. These glorified tool sheds have no plumbing, and many have no insulation or fire protection. But they do have windows, and some are wired with an electrical outlet.

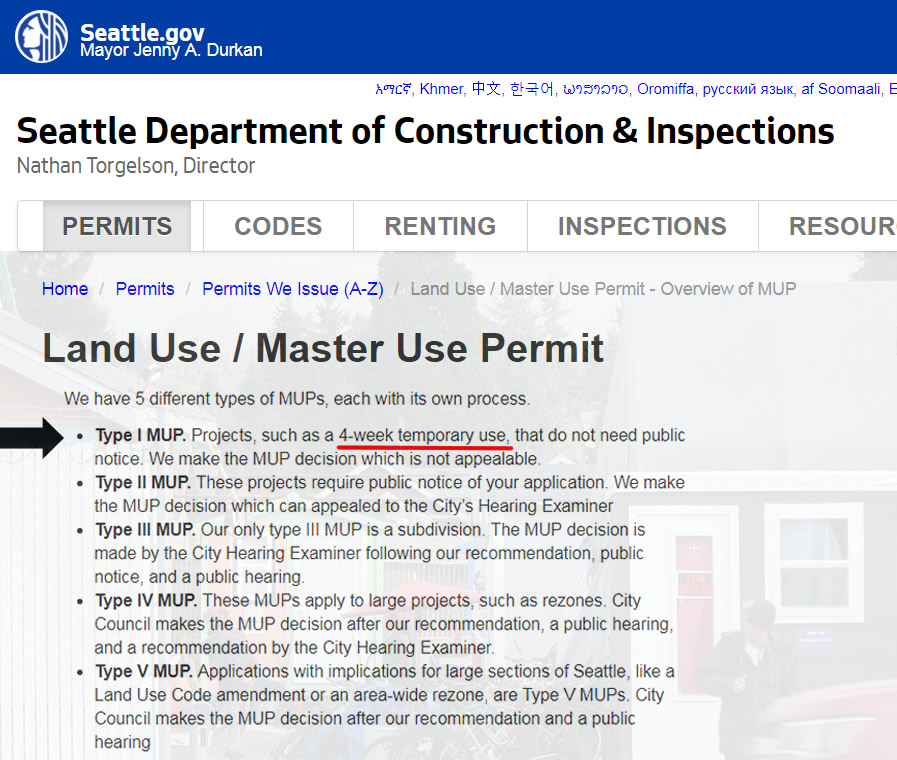

The City treats the camps as a Type I master use permit. Type I covers temporary uses like Christmas tree lots and seasonal carnivals. Since these activities are brief and have minimal impact on a neighborhood they don’t need a public input process or other red tape. Accordingly, once a Type I permit is approved by the Department of Construction and Inspections, the decision can’t be appealed.

Home Sweet Homeless Camp: The Nickelsville Ballard tiny house village overstayed its permit by several months. When the permit expired, the camp operator refused to leave until the City found the camp a bigger place to stay, which the City finally did.

The Type I master use permit wasn’t created with homeless camps in mind, but considering how controversial these camps are, it comes in very handy. The City doesn’t have to consult with a neighborhood before agreeing privately with operators to place a homeless camp there. And once they’ve made their decision, they can announce it as an accomplished fact. Which they do.

According to the sanctioned homeless camp contract, which is slightly more stringent than the land use code, the City agrees to notify property owners within 300 feet that a camp is being planned and hold a public meeting to take questions and comments. But even under the contract, the City isn’t required to consult with neighbors before choosing a spot. So they don’t. Once a camp is announced, neighbors can register their opposition, but that feedback doesn’t factor into whether the camp is going on, because the City and camp operator have already decided on that.

Homeless camps are granted an expedited review process by the City of Seattle. Public comment is not taken prior to the siting of a camp and the City’s decision to permit cannot be appealed.

According to the contract, homeless camp operators must still obtain a master land use permit to set up a sanctioned encampment within the city limits. The initial permit is good for one year and can be renewed once after the first year, which means, theoretically, that homeless camps can be in one spot for a maximum of two years. Before the renewal permit is granted, the City agrees to open a comments period and host at least one public meeting to take live testimony. Citizen input is supposed to be collected and reviewed by someone before the renewal is granted. But as with the initial permit, the decision to re-permit rests entirely with the City. And there is no appeal.

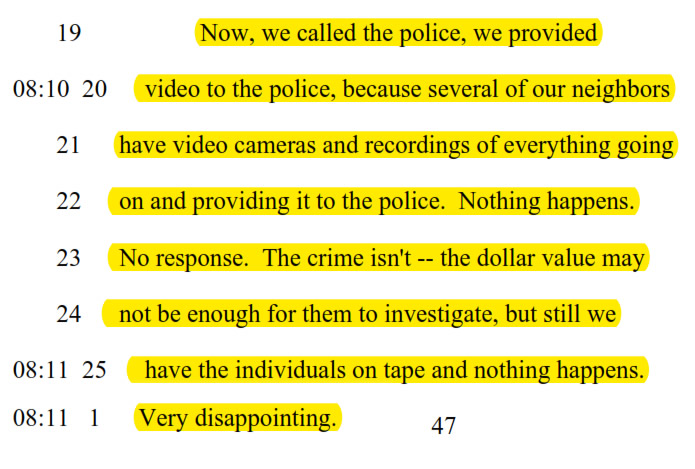

Very disappointing: Testimony from a Licton Springs Village neighbor belies the operator’s claims that the city-sanctioned homeless camp is not correlated with a rise in crime. (This testimony was taken from Page 45 of the transcript below.)

Licton Springs Village

By the early spring of 2017, the City had created four sanctioned homeless encampments, all run jointly by the same two organizations: SHARE and the Low Income Housing Institute (LIHI). (I have written extensively about both of these troubled organizations.) The camps were originally claimed to be drug- and alcohol-free, but as the network of camps expanded, the City and camp operators said they wanted to try a new model of camp they called “low barrier.” Low-barrier camps were supposed to help hard-to-serve street dwellers who had “barriers” like active drug addiction or lack of ID that would prevent them from using shelters or the original sanctioned camps. The first of these camps was scheduled to be installed in the Licton Springs neighborhood in the early spring of 2017.

The Licton Springs neighborhood in north Seattle runs along what used to be the main traffic route through Seattle: Highway 99, but the motor hotels that were the glory of roadside America have aged into seedy flophouses, and stretches of the road have become havens for drug users and prostitutes. As you can imagine, when the HSD announced it was putting in a camp where people could use drugs without fear of arrest, the neighbors weren’t amused. The camp was supposed to absorb at least some of the existing vagrants. But what if it becomes a magnet for even more of them? the neighbors asked. –That’s why we’re taking your input now, the City said. And that’s why we’ll have another meeting after a year. If the camp doesn’t work out, we won’t renew the permit, and they’ll have to go.

The City didn’t mention that by the time Licton Springs Village was announced, the camp operator had already purchased the lot on which the camp was to be located, and HSD had already agreed with the operator to put the camp there. Given that, and given all the trouble the City would have to go through just to get the camp up and running, how realistic was it to expect that the City would pull the camp’s permit after only a year?

They get around: When the gates to the Licton Springs sanctioned low-barrier encampment in North Seattle are open, you can see dozens of bikes stored inside.

We told you so!

On March 26, 2018, approximately one year after the camp opened, the City of Seattle and the camp operator hosted the promised community meeting to get feedback from the neighbors. That meeting was held on the campus of North Seattle College, and I was in attendance. Some students from the University of Washington School of Public Health spoke in favor of the camp, and a staff person at a nearby shelter for prostitutes spoke in favor of repermitting, as did three residents of the camp. But the balance of public comment – most of it from the camp’s neighbors – was clearly against.

Neighbors said that after the camp went in, they noticed an immediate increase in property and nuisance crime and that this was contributing to a general degradation in the livability of the neighborhood. Accordingly, they did not want the permit renewed.

You can read the transcript below to get a mood of the meeting. Everything through page 35 is from people the City and camp operator had invited there. From page 36 to 66 are the actual public comments, and, as you can see, they’re critical:

LSV-Community-Mtg-Transcript-03-26-18

Incredible Progress: This woman manages a women’s shelter and recovery program nearby the Licton Springs Village. She said: “I have personally seen people’s health improved. People who are now clean and sober, who were not clean and sober before the village. We’ve seen incredible progress by people and people that have been traditional sprawlers along Aurora, who I’m sure many of you have now seen are now housed in Licton Springs.” She forgot to mention that the Commons had been closed due to a rash of crimes in the area just two months earlier. [Her commentary begins on page 34 of the transcript.]

A tenfold increase in crime: This woman questioned the City’s official statistics. “I’ve seen car prowls, assaults, drug activities, needles. Not only car prowls but going into people’s garages, going into people’s homes, going into their yards, and one woman [ . . . ] even assaulted with a gun as she was getting off the bus walking to her home.” [Page 44 of the transcript]

Going through my bin. This man who’d recent bought a home in the area said: “It all started when my car was prowled. Shortly after we found needles next to our garage. Then we had someone that I would assume was homeless or near that area walk into our yard, start yelling at us for beer while we ate dinner with our family. I did, however, have a nice conversation with a woman who was going through my recycle bin looking for magazines.” [His testimony starts on page 46 of the transcript.”

The report below, from the Seattle Police Department data section, corroborates what the neighbors said about crime increasing around the camp. Comparing totals from 2016-2017 (the year before the camp was there) and 2017-2018 (the year after the camp was there), the report showed there were increases in all areas, with the highest, at about 100% being for overall crime:

Several news outlets have covered this trend as well:

The camp residents at the meeting didn’t question what the neighbors were saying about increased crime, but they said the crimes weren’t being committed by the camp residents themselves. While that might be true, it’s beside the point. Homeless camps – especially the low-barrier ones – attract drug dealers, who supply the users in the camps. And those dealers attract other drug users, who often must resort to crime to support their habit. When word gets around that there’s a homeless camp in the neighborhood, vagrants and petty criminals of all kinds congregate there, because to them, the camp is a beacon of tolerance. Or perhaps of neglect.

For their part, Human Services staff have told people who have complained about Licton Springs Village that the north Hwy 99 corridor was always a high-crime area, but that’s cold comfort. What they hear the City saying is that they should be used to crime by now, so a little more can’t hurt them.

Surprise: The permit was renewed!

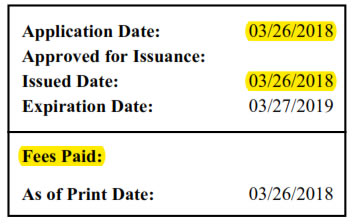

Citizens who couldn’t make the March 26 meeting could still submit comments to the City. The public comment period began a week before the meeting and ended about a week after, on April 4. According to the contract, the City was supposed to wait until April 4 and then review comments and decide whether the camp’s permit would be extended for another year. But they didn’t bother to wait. Sometime shortly after March 26 – and possibly even before – the camp’s master use permit was renewed for another year and dated to the 26th. According to the permit record, which is displayed in full in Appendix A, the application was approved and entered into the files on the same day it was submitted: March 26… which was the same day the community meeting was held and eight days before the comment period ended. Also notice that no document review fee was paid by the camp operator. And why would there be, since the City didn’t actually review anything.

A prostitute works the street across from the Licton Springs Village “low-barrier” homeless camp on North Aurora. Though prostitution has been a problem in the area for several years, neighbors report that it’s gotten worse since the camp came in. Some of the camp residents are drug addicted prostitutes.

A suspicious pattern

There are nine sanctioned homeless camps in Seattle, with more on the way. Of those, three have overstayed their maximum permitted time by several months, and one (Othello Village) is apparently intending to stay in the neighborhood indefinitely. After Othello Village’s s two-year permit lapsed, a local church volunteered to “sponsor” the camp by leasing the land from the owner, LIHI. This means the camp is eligible for a conditional use permit allowing it to stay indefinitely as a Constitutionally protected expression of the church members’ religious beliefs. But church sponsorship of homeless camps is just another ruse, as we saw with the Dearborn Nickelsville camp. Church-sponsored camps don’t have to be on church property, and sponsoring church members don’t have to spend any time with the campers. Church sponsorship may become superfluous in any case, because LIHI has said it will push the City to rewrite the contract language to let camps stay beyond the current two-year maximum. And the City will almost certainly acquiesce.

No sanctioned homeless camp has ever been denied an initial permit or a renewal, and there is a sense among Seattle residents living around the camps that everything about the camp permitting process is just a pro forma exercise, a sham of public process. With the possible exception of Camp Second Chance, Licton Springs Village has been the hardest on its host neighborhood, and yet, even though many neighbors complained about a rise in crime, and even the data supported their accounts, the City more or less automatically renewed the camps permit, making the whole public input process a charade.

In her comments at the community meeting, HSD’s Lisa Gustveson told neighbors that the City’s decision on whether to repermit Licton Springs Village would happen after the comment period closed in two weeks. But in fact, the decision had already been made. Click to enlarge this image.

Why even bother with “the process”?

It’s not hard to understand why the City would want to ignore public process on sanctioned homeless camps. Bringing a new camp online or moving an old one takes months and sucks up thousands of City staff hours. Political capital is expended as well, because wherever the City opens a new camp, it costs the councilmember for the district it’s in votes. It’s only natural, then, that City officials are loathe to cancel a permit after one year and take the camp somewhere else. Especially if they had no other place to take it. If the neighbors were unhappy enough, another option would be to turn the campers back out on the streets, but that’s the last thing the City would do, because the camp operator would almost certainly stage a protest, and even if it didn’t, closing a camp would be a reminder that that camp, and the whole camp model, was ultimately a failure. Accordingly, no camp has ever been shut down; just the opposite in fact. Like duckweed in a farm pond, the camp network is always growing, and never shrinking.

The Type 1 permit is for short-lived land uses that have low impact on neighborhoods. The City of Seattle is using them to permit homeless camps that are high impact and can stay in a neighborhood for years.

So why does the City even bother with the pretense of neighborhood involvement? If they’re going to do whatever they want, why don’t they just do it and stop wasting people’s time pretending to care? The answer is: politics. It’s just good public relations for government officials to turn up at a community meeting and let people ramble for a couple hours, even if they spend most of their time complaining. It helps tamp down resistance.

Soon… a reckoning?

The situation with Seattle’s sanctioned homeless camps seems untenable: Other than PR value, they don’t deliver much for the money, and they generate a lot of bad will in the neighborhoods. And yet the City keeps adding camps and lavishing more money on the operators every year. How can they do that? To understand it, you have to understand the political landscape. There are 700,000 people in Seattle, but only ten thousand or so of them live close enough to a homeless camp such that they might make a connection between the camp and increased crime in the neighborhood. Of those living near to a camp, many will be young social justice-minded renters who buy the City’s argument that the camps are doing something about homelessness and any bother they cause is small price for those who are “privileged” to live indoors to bear in order to help out the less fortunate. People who accept that claim likely won’t accept counterclaims that the camps aren’t working and that they might, in fact, be counterproductive. Or at least, they won’t accept it easily. Of the sanctioned camp neighbors who get that there’s a basic problem with them, many will simply leave the area rather than fighting, and that leaves those who stick it out feeling increasingly isolated and powerless. Citizens who speak out consistently against the sanctioned camp system are marginalized and scorned as NIMBYs by Seattle’s left-wing political establishment.

Despite the strongly left-leaning political complexion of Seattle media, the are a handful of relatively non-biased local sources – led by the Seattle Times – that could be doing a better job of exploring this issue. Unfortunately, making “tiny house villages” look bad isn’t a growth industry in a town like Seattle, so they generally leave it alone. Such sanctioned camp stories as the media do produce tend to be either superficial or positively flattering to the camps, like this one by the Wall Street Journal, for example. Once in a while, a thoughtful critique will appear, and when it does, it gets some attention. But the excitement fades in a day or two, and no one follows it up. Meanwhile, no one other than the Blog Quixotic is continually investigating the camp operators or their relationship to local politicians. And no on is asking the tough questions about whether these sanctioned homeless camps are solving homelessness… or making it worse.

There will probably never be enough popular anger at the camp system to shut it down, but in the broader political sense, there’s still much cause for optimism, because with each passing week the City’s failure of leadership on the homeless issue generally is costing it more. Vagrancy has been on a steady upward trend since the first camp opened, with some lurid new case of squalor or crime making the news almost daily. After 10 years of rising taxes and deteriorating conditions on the street, the voters are getting disgusted. In May, a relatively modest City Council scheme to raise $50 million for homeless spending through a head tax on City employers was overturned by voter initiative within month of its passage, and there is now talk of a new crop of outsiders – neighborhood activists – rising to challenge the incumbents in the 2019 City Council elections. I’ve interviewed several of these prospective challengers, and they’re all running on an anti-vagrancy, pro-accountability platform. That’s going to be a problem for the incumbents, because they are all associated in the voters’ minds with both homeless camps and the rise in vagrancy.

So there might yet be hope that the voices of Licton Springs Village neighbors will be heard.

–By David Preston

All pictures are by the author, City of Seattle, or anonymous.

I thank the following people for their support, both moral and editorial, in the creation of this and other articles about the Homeless Industrial Complex:

Elisabeth James

Jennifer Aspelund

Aden Nardone

Amber Matthai

Chad Smith

Avril Barlow

Do you like this investigative journalism? Then reward me.

~ Postscript ~

Community Advisory Councils: Another brick in the wall

Josh Castle selects members of the Community Advisory Councils and is camp operator LIHI’s man on the scene at community meetings. Here he is at the Licton Springs Repermitting meeting in March.

Another reason why sanctioned camp neighbors don’t trust the input process is because of their experience with the Community Advisory Councils (CAC). As part of the sanctioned encampments contract, each camp is required to establish a CAC of some half a dozen “community members” who will hold monthly meetings, take public input, and advise the City and the neighbors on the operations of the camp. The CAC is marketed to camp neighbors as being their own little camp monitor, but in fact the CACs are as fake as any other part of the facade.

CAC members aren’t chosen by the neighborhood; they’re selected by the camp operator. Accordingly, people who are in any way critical of the sanctioned camp model or the operator are never appointed to be on these things. Only those who can be counted on to cheer for the camp – or at least stay out of the way – are chosen. A typical CAC might include a local pastor whose parishioners bring meals to the camp; a manager at a non-profit that, like the camp operator, depends on the funding from the city; an ex-resident of the camp, a sympathetic local housewife; and one or two social justice activists. CAC members are not required to live near the camp they oversee.

The CACs don’t act as advocates for the communities surrounding the camps, and neighbors who have tried getting satisfaction through them are always frustrated. The response people living around the camps get when they complain about trash or increased crime is the same one they got at the March 26 meeting: “It’s not the people at the camp who are doing these crimes, so it’s not our responsibility.”

And yet another thing…

Apparently, Licton Springs Village was never granted a master use permit for the first year it was in operation, because there is no record of such a permit on file with the City. If you do a Permit and Property Records Search and search on the address 8620 Aurora Ave N, you will see a list of permit-related documents for the camp. The search returns 23 documents, including the 2018 master use permit renewal for that camp, but there is no permit for the property for the time it was being operated between the spring of 2017 and March 26, 2018. There are construction and electrical permits for the camp’s first year, but no land-use permit.

That could be because the paperwork wasn’t scanned and uploaded into the database, but given how important the master use permit is relative to the other documents, that is unlikely.

Appendix A

The Licton Springs Camp Master Use Renewal Permit

licton_springs_camp_2018_permit

Appendix B

Licton Springs Village Visitor Packet

This document was prepared by camp operator SHARE to give to Licton Springs Village visitors and the media. It was also handed out at the March 26th community meeting. The camp receives several hundred thousand dollars a year in subsidies, but note that SHARE is asking visitors for basic items like food and blankets:

Appendix C

Testimony and documentation from students at the University of Washington School of Public Health

At the March 26th community meeting, these college students and their adviser praised the Licton Springs camp and presented a report that they claimed showed crime hadn’t increased at the encampment in the first year of its operation. Here’s a transcript of their testimony, along with the report they submitted.

Bibliography

In reverse chronological order

Seattle to improve security near tiny house village after complaints. (KING5 News, July 31, 2018)

No link between homeless villages and crime rates, Guardian review suggests (The Guardian, May 23, 2018)

Crime reports spike as tiny house village seeks permit renewal. (KOMO News, April 26, 2018)

This tiny house village allows drugs. (Seattle Times, April 23, 2018) Note that the Times uses the camp operator’s “tiny house village” terminology to describe the camp.

Licton Springs Homeless Village: This is Seattle’s first low-barrier shelter. Residents can stay while here while drunk or high on drugs. (KSLTV Enterprise Team, May 26, 2017. YouTube video.)

Tiny Homes: Seattle’s Latest Solution to Housing Homeless (Wall Street Journal, April 26, 2017)

END

Awesome!!!

I truly appreciate this article.Thanks Again. Want more.

I’ve been on the Othello Village CAC since its beginning. This tiny house village has always had good community support because the residents have helped with community projects, such as clean ups, and because it has not increased crime (it’s not a high crime area like Aurora). However I never paid much attention to what was happening in the village until the last few months, when we heard that some residents had been complaining to the LIHI case managers about unjust “bars” and that residents were being told to not talk to the case managers. LIHI had been attempting to work these issues behind the scenes but with little success.

Finally the city decided to require a “Memorandum of Understanding”, to spell out LIHI and Nickelsville rights and responsiblities. Scott Morrow rebelled against this because a key requirement was that residents could appeal a “bar” to LIHI as a last resort. I realized that Scott was tall on “self-governance” but short on that other essential feature of democracy – “oversight and accountibility”. There had also been a number of incidents of irrational and unethical behavior by Scott, which I found extremely disturbing. These continue to this very day, so I’ve conclude that he needs professional mental help.

BTW, I came on as a community activist, knowing little about Scott, but our two newest members are definitely in his camp. He has repeatedly stonewalled on replacing members who’ve resigned. Thanks for asking hard questions. I want to see Othello Village continued but not with Scott at the helm.

Man… its summer 2020 and things have only gotten much, much worse. The 2019 elections were a disaster. Just more alt-left clowns in our government. And now the riots and violence from the deranged left. Seattle has been in a downward decline for at least twenty years but it’s gotten really bad in the last five years. Arm up and ammo up. Once SPD is gone, it will be up to us to protect our property and lives.