April 19, 2019

For a scientist devoted to social justice, where does science end and advocacy begin? Does the scientist have a right to shape her study results to support a cause she knows to be worthy? Universities take money from corporations and military all the time to fund research that fuels big business and war. Why can’t an individual, socially conscious academic do a similar good turn for her comrades fighting the war on poverty?

Dr. Amy Hagopian is an Associate Professor at the University of Washington School of Public Health. She’s also an enthusiastic participant in a number of local political causes, including military counter-recruiting, the Boycott-Divestment-Sanctions (BDS) movement, and homeless rights advocacy. Her involvement with the homeless rights issue led Hagopian, several years ago, to begin collaborating with a non-profit group called the Seattle Housing and Resource Effort or SHARE and its charismatic leader, Scott Morrow. This is the story of how her connection with that group compromised her objectivity and cast doubt upon the credibility of her department.

social justice as a “family business.”

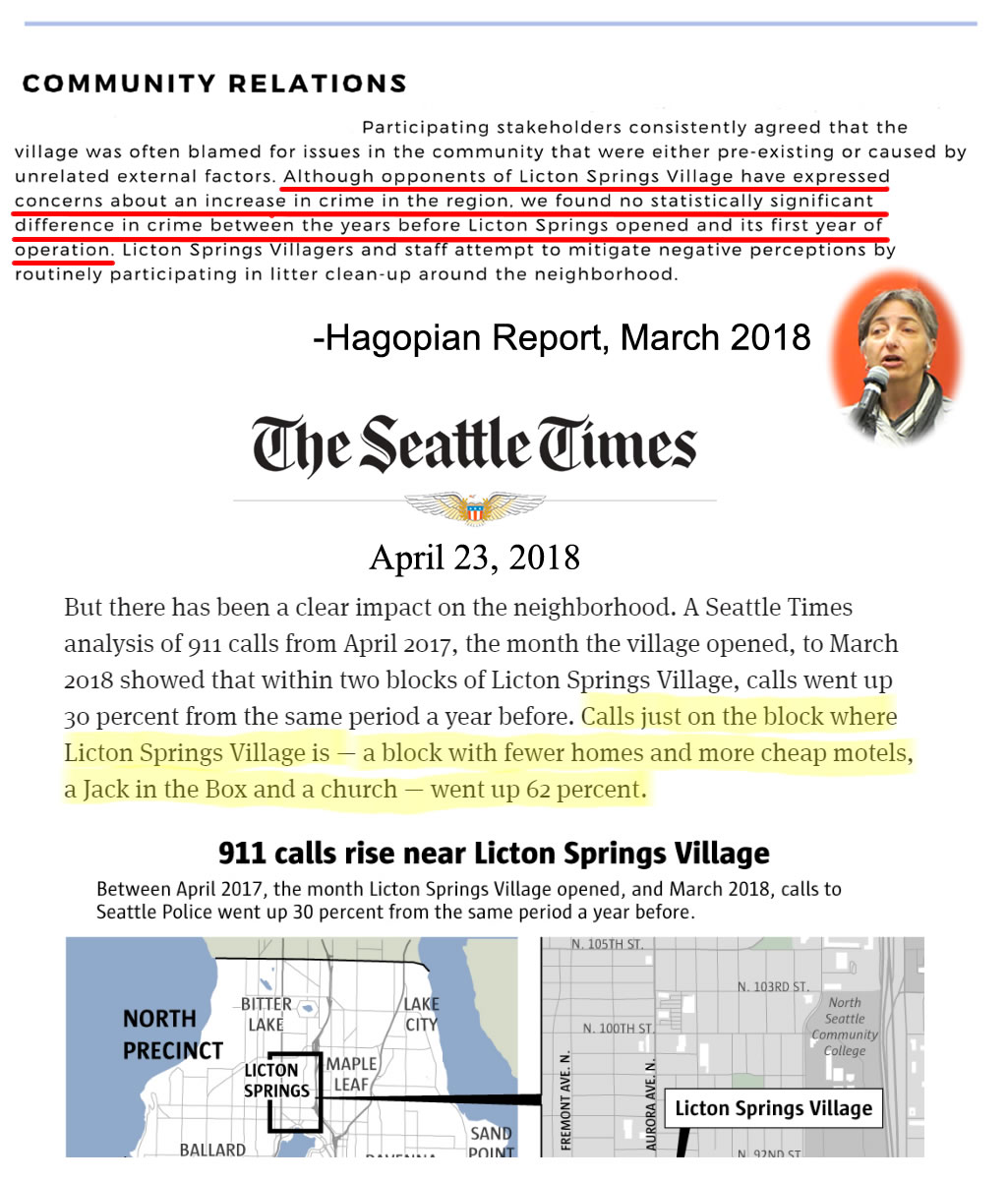

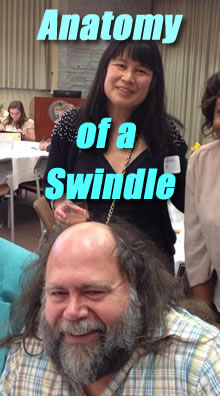

I first met Ms. Hagopian in 2008, when I was in the peace movement and was, like her, involved in military counter-recruiting. The next time I saw her was on March 26, 2018, when she appeared at a community meeting at North Seattle. Hagopian was there defending a City of Seattle-sponsored homeless encampment known as Licton Springs Village. Hagopian had been invited by the manager of the camp, SHARE, to present an “executive summary report” of a study she and her School of Public Health students had done on the camp’s effectiveness and its impact on the neighborhood. The introduction claimed that the study was commissioned by SHARE.

Dr. Hagopian speaks at a community meeting to decide the fate of the Licton Springs Village sanctioned homeless encampment on March 26, 2018. (Photo by the author.)

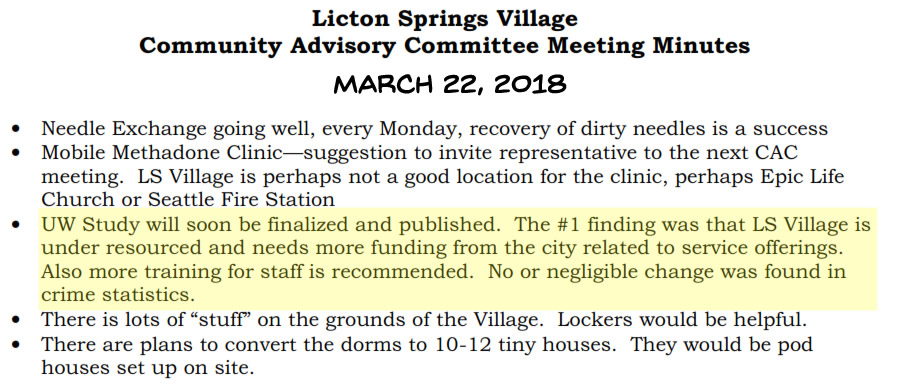

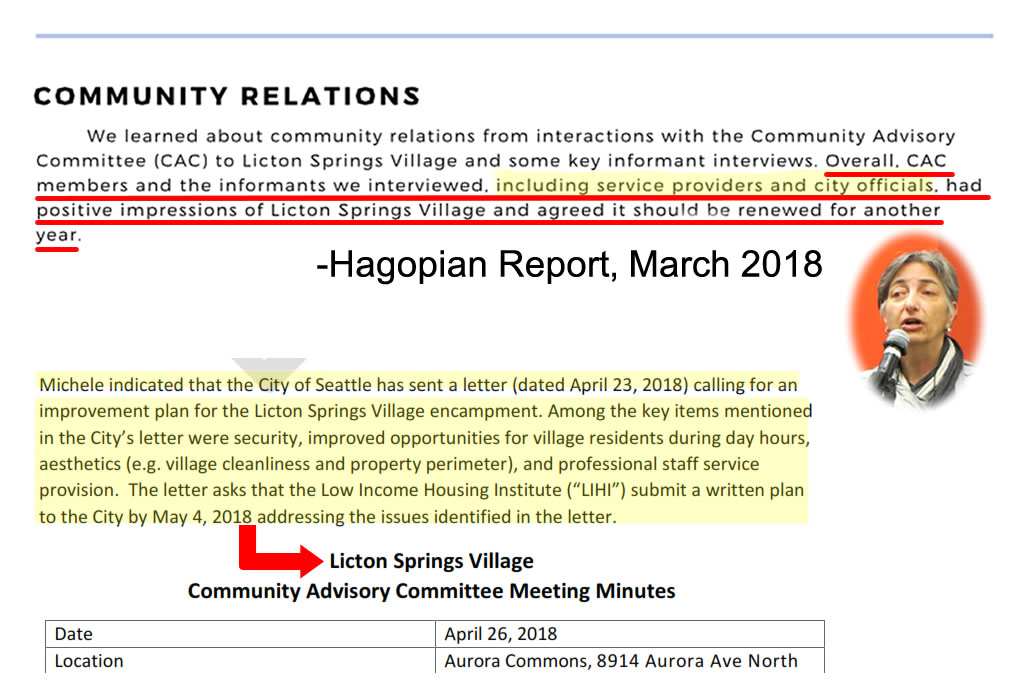

In her remarks to the audience, Hagopian claimed that the camp was moving significant numbers of homeless people into permanent housing. She also said that crime had not gone up in the surrounding area in the year the camp had been there. Hagopian and her students took turns at the mic, extolling the camp’s effect on the homeless people who lived there and contradicting the neighbors’ claims about increased crime and squalor they said had followed the camp’s arrival. Neither Hagopian nor any of her students lived in the Licton Springs neighborhood.

Hagopian finished by recommending that the camp be repermitted for another year. For a transcript of her remarks and more on what happened at the meeting, go here.

After digging into Hagopian’s report later, I discovered a number of problems with it. I also discovered that the relationship between Hagopian and SHARE was much closer than I’d thought. So close, in fact, that it called into question Hagopian’s ability to produce a scientifically rigorous study on any project SHARE was involved with.

(For a point-by-comparison between what Hagopian’s summary report and what was reported at the Community Advisory Council and elsewhere, see Appendix A.)

In late October, I sent Hagopian a certified letter challenging her on various aspects of her report and her relationship with Morrow and SHARE and asking her to respond. Salient questions included:

- How much did SHARE pay to have the study done?

- Did Hagopian submit a study design for review or publish her findings?

- Why didn’t she disclose her and one of her student’s relationships to SHARE to the community meeting where she presented the report?

- Why were there discrepancies between what Hagopian’s study found in terms of “exits to housing” from Licton Springs Village and what the Human Services Department’s Lisa Gustaveson reported?

- Would Hagopian go back and update her study report based on crime data published by the Seattle Police Department that contradicts her own claim that crime around the camp was stable during its first year of operation?

Here’s a copy of the letter, including the two attachments. It contains several specific items challenging the accuracy of Hagopian’s evaluation:

Certifed-Letter-to-Amy-Hagopian2I didn’t get a return card from the UW showing they’d received the letter, so after two weeks, I e-mailed Hagopian a copy of it asking her to respond. She got back to me by e-mail and we exchanged messages over a period of days. The entire e-mail chain is here:

Hagopian-emailsDr. Hagopian was not responsive to most of the points in my letter, but she did give me at least some useful information. Here’s what I gleaned from her responses, or lack thereof:

- Hagopian was not, in fact, commissioned to do the report. By SHARE or anyone else. She volunteered to produce the report for SHARE, at taxpayer expense.

- Students spent an estimated 1,440 hours on the report (8 students x 18 hours per week x 10 weeks). The value of this work, estimated conservatively at $15 per hour, would be $21,000. That does not include whatever time Hagopian herself put into it, nor does it include the cost to the School of Public Health to print copies of the glossy brochure that were handed out at the meeting.

- Dr. Hagopian told me that she didn’t consider her report or the underlying study to be research, and that’s why it was not reviewed by anyone. She didn’t keep any of the survey instruments or the audiorecorded interviews.

- She gave no explanation for the discrepancy between her numbers on homeless exists and Ms. Gustaveson’s, and she didn’t answer my question about the updated Seattle Police Department crime data. She merely claims that she talked with SPD and an unnamed “big data” guy.

Hagopian didn’t answer my questions about why she didn’t identify her and one of her student’s relationships to SHARE to the public either in her public remarks or in the summary report itself. She merely said that she “maintain(s) relationships with several community-based organizations so as to provide opportunities for my students to do projects.”

Let’s take a look at the relationship she’s maintained with Scott Morrow and SHARE over the years. There’s no shortage of material out there attesting that it was a close one.

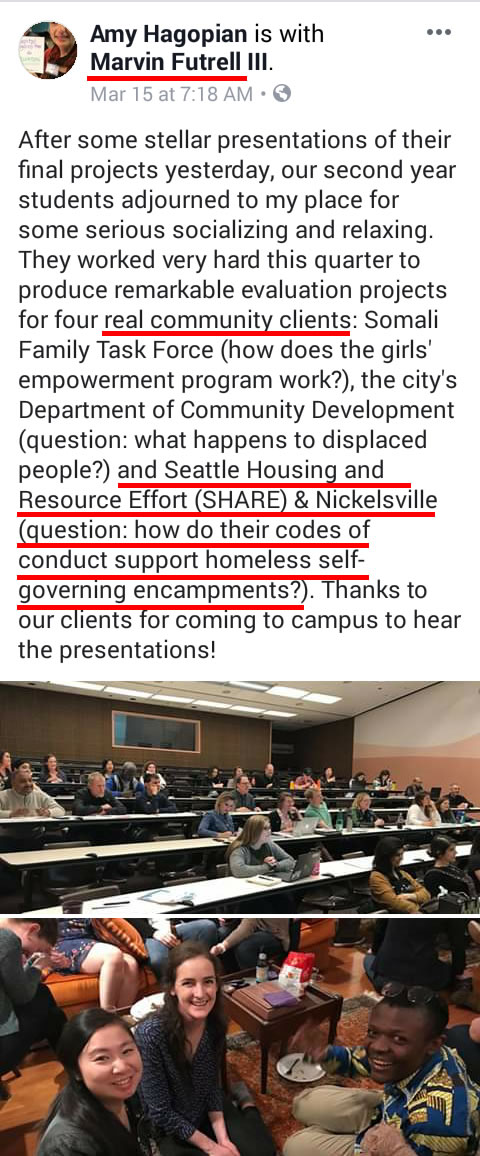

◄◄◄ In this post on Facebook, Hagopian tags SHARE employee Marvin Futrell and praises SHARE and its subsidiary, Nickelsville, referring to them as her “clients.” Futrell has been a controversial figure within SHARE and has been described as an “enforcer” by SHARE staff and camp residents. He’s the subject of a underground comic, Bossman, which was produced by SHARE board member Stu Tanquist (now deceased) and distributed widely in homeless advocacy circles in 2016.

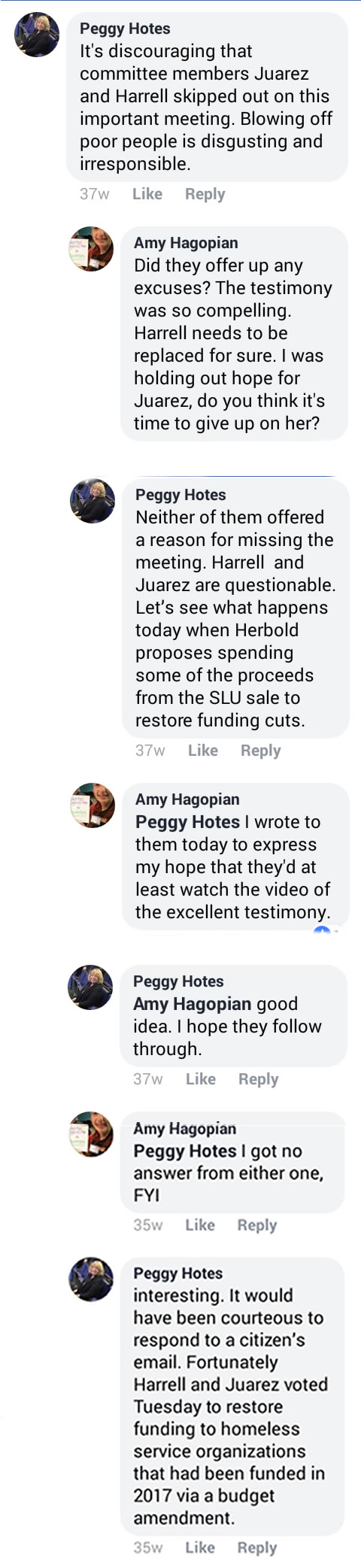

In this Facebook exchange ►►►

SHARE co-director Peggy Hotes and Hagopian discuss a move by Seattle Mayor Jenny Durkan to cut SHARE’s church shelter program out of the budget for non-performance. During this time, Hotes, Hagopian, and other SHARE supporters were lobbying the City Council to override Durkan’s budget and restore SHARE’s funding.

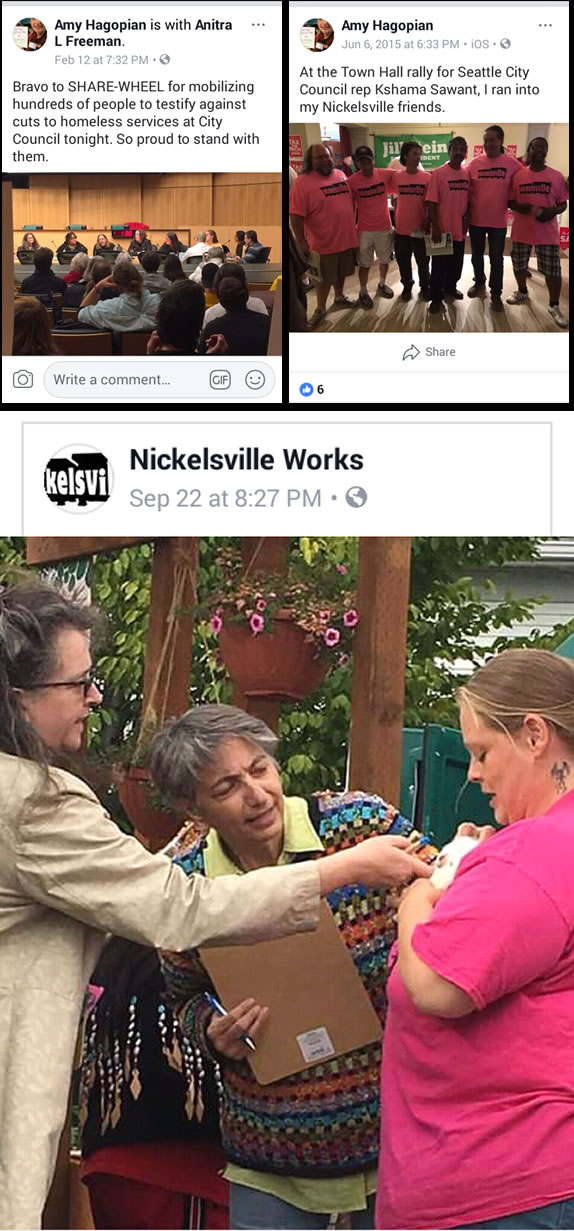

In the top row of images below, Hagopian is cheering SHARE’s lobbying efforts at City Hall. In the bottom one, she is shown judging a pet show at one of the Nickelsville homeless camps run by SHARE. That photo was posted on a Facebook page called “Nickelsville Works” which is run by Peggy Hotes of the SHARE organization. The Nickelsville non-profit corporation is an arm of SHARE. ▼▼▼

In the image below, Dr. Hagopian is on the left in red. In the center of the group stands SHARE enforcer Marvin Futrell. On the right is SHARE boss Scott Morrow. In the blurb, Hagopian appears to be referring to SHARE staff as her colleagues. ▼▼▼

The Facebook posts below, created over two years apart, show Hagopian again lobbying on SHARE’s behalf. Note: The Stranger editorial that Hagopian approved with a “Yep.” was written by Katie Wilson, director of a group called the Transit Riders Union. The TRU, which isn’t a union and doesn’t have that much to do with transit, could be considered another SHARE front group, since it is present at every pro-SHARE rally at City Hall and has been a number of City Council committees tasked with finding more money for homeless programs. ▼▼▼

Which side are you on?

In late March 2019, SHARE became involved in a power struggle with one of its spin-off groups (the Low Income Housing Institute or LIHI) and the Human Services Department (HSD) over control of three “sanctioned” (i.e. city-permitted) homeless encampments it had been operating under the aegis of LIHI but with no direct financial support from the City. LIHI had recently been forced by HSD to close another camp it had run jointly with SHARE because of deteriorating conditions, and, now, wary of the public relations damage it was sustaining because of its alliance with SHARE, LIHI decided to oust SHARE from the remaining three camps it managed. In protest, SHARE staged rallies at each of these camps. Photos taken at the Georgetown camp rally and posted on SHARE’s “Nickelsville Works” Facebook page show Dr. Hagopian in attendance, along with several other SHARE stalwarts. In this photo Hagopian is shown applauding as socialist firebrand Councilmember Kshama Sawant lambastes LIHI and HSD.

Two weeks later, HSD interim director Jason Johnson released this statement supporting LIHI’s decision to take over the SHARE camps. The “CAC letter” he refers to is a letter sent by one of the “Community Advisory Councils” to HSD, asking Director Johnson to clarify HSD’s position on the camps. In his response, Johnson expresses his disapproval of SHARE’s misrepresentation of the City’s position and its threats to cut off food from the camps if LIHI took aggressive measures to retake the camp. This was particularly worrisome, Johnson said, in view of the fact that there were children living at the camps.

And this was the organization, SHARE, that Hagopian was supporting at Sawant’s rally. An organization that would cut off food to homeless children to spite a government agency.

In case there was any doubt about what Hagopian’s presence at the Nickelsville Georgetown signified, here she is two weeks later, describing her visit to SHARE boss Scott Morrow, who was still holed up in the kitchen at the Othello Street Nickelsville, supposedly resisting the LIHI takeover. Hagopian wishes there was some “good journalism” in Seattle, by which she presumably means pro-SHARE, pro-Morrow journalism. Just like her good evaluation of the Licton Springs Village. ▼▼▼

SHARE has been in the news quite a bit lately, as the subject of numerous complaints by residents, complaints of the type that have been discussed and documented by this page a number of times over the years but which, until recently, have not been picked up by mainstream media. The group had setbacks at City Hall as the pro-SHARE head tax was defeated and two SHARE-friendly councilmembers (Bagshaw and O’Brien) decided to retire. In January, Mayor Jenny Durkan nominated SHARE nemesis Jason Johnson to be head of Human Services, and so worried is SHARE about a Johnson regime at HSD that the group has held anti-Johnson rallies at City Hall. Meanwhile, SHARE’s strongest remaining ally on the Council, Kshama Sawant, has tried, unsuccessfully, to get her colleagues to reject Johnson. It looks like Johnson will be confirmed, though, and when he is, he’s likely to call for an audit of SHARE as a condition of the HSD doing any more business with the group. Rather than submit to an audit, SHARE will disengage from HSD and may even close its shelters and whatever tiny house villages it has left. At that point, the SHARE era will come to an end. At least in Seattle.

What did she know and when did she know it?

We can expect many more stories of SHARE abuses to come out in the wake of the group’s collapse. As that happens, some of SHARE’s more respectable allies, like Dr. Hagopian, will be asked how they could have given the group such uncritical support over the years. Will Hagopian be let off the hook? Considering the closeness of her relationship to Mr. Morrow and his group, it’s doubtful. How could she NOT have known what was going on?

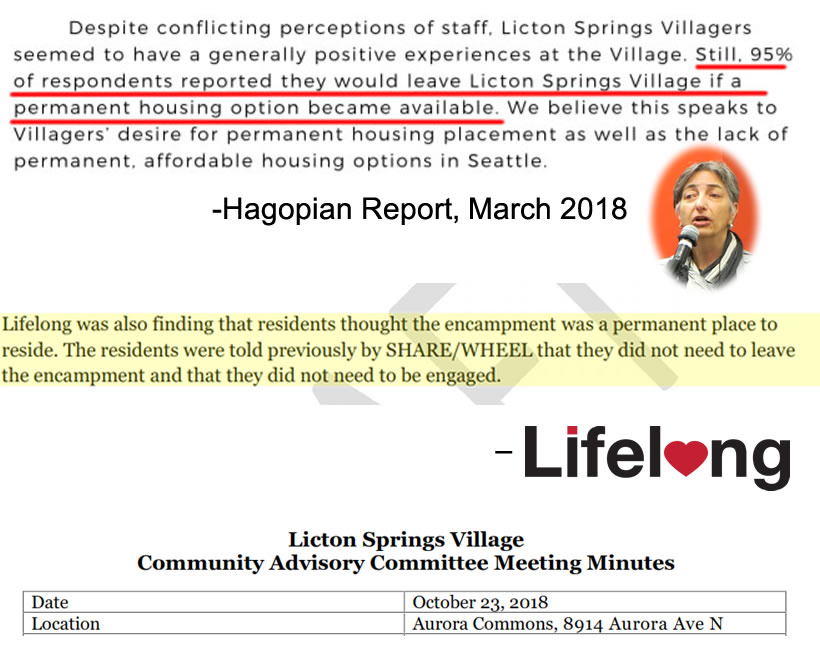

Let’s go back to Licton Springs Village Hagopian produced an evaluation report purporting to show that the homeless camp was (a) successful at getting homeless people into permanent housing and (b) not a burden on the surrounding neighborhood. However, just one month after Hagopian presented that study, HSD demanded that the camp’s sponsor, LIHI, submit an “improvement plan,” * and one month after that, the agency announced it was closing the camp for good, for reasons that contradicted Hagopian’s findings. In contrast to what Hagopian’s evaluation claimed, HSD found the village wasn’t, in fact, getting residents into housing and that it was having a profound and negative impact on the neighborhood. Although SHARE was managing the daily operations of the project, the Low Income Housing Institute was in charge, and one of the first things LIHI did was to remove SHARE from the project and hire another non-profit, Lifelong, to do what SHARE was supposed to be doing but wasn’t. When Lifelong came in, it discovered that SHARE had not even been keeping records on who was there. According to a woman named Nosilla Duke, who attended meetings of the Community Advisory Council during this period, the City’s contract stated a program goal that 50% of camp residents would be moved into housing, yet by 18 months into the program only 20% of the total number of residents up to that point had actually been moved into permanent housing. When SHARE left in October of 2018, they did not provide a list of remaining residents, and at the October meeting of the CAC, a Lifelong representative said they weren’t even sure was supposed to be living at Licton Springs Village (see Appendix A, October minutes). There was no operations manual, Lifelong reported, nor any specific documentation on any of the residents or their needs.

Dr. Hagopian claims that her students spent 1,440 hours working on the project, and that’s in addition to the considerable number of hours she spent on site at the Village herself. Is it possible that, during all that time, she and her students wouldn’t have observed what was actually going on at the camp? Or did she see what was happening and choose not to include it in her evaluation, because that would have reflected badly on SHARE and her friend Scott Morrow?

A Hagopian/SHARE Timeline

Let’s review Dr. Hagopian’s relationship to SHARE over time. This list includes just those things one can easily find on the Internet. There are likely many more items that aren’t a part of the public record:

- Spring 2009: Hagopian teaches two courses (that involve a collaboration with Scott Morrow, whom Hagopian lists in the syllabus as “supporting faculty” for the course. (Note that the reading materials include Saul Alinsky’s Rules for Radicals and an interview with Alinsky from Playboy magazine.) She still teaches one of these courses (HServ572) today, though the name has changed from “Community Development for Health” to “Planning, Advocacy, and Leadership.” (With emphasis on the advocacy.)

- April 2009: Scott Morrow gets a “community partner” award from Dean Patricia Wahl at the University of Washington’s School of Public Health. The article on SPH’s Web page says this: SHARE and WHEEL are self-organized, grassroots organizations of homeless and formerly homeless individuals. SHARE supports the operation of Tent City, whose residents have welcomed our students’ visits and support for several years. Morrow has enhanced the learning experiences by connecting students with residents who participate in the Department of Health Services’ Community Development for Health course. Tent City residents also served on a panel organized by Students for Equal Health and have agreed to be subjects for a thesis project.

- November 2010: Hagopian is appointed by Mayor Mike McGinn to his “Encampments Task Force,” which is charged with finding public land on which SHARE can locate their tent cities.

- Winter 2016-2017: Hagopian and Sally Clark, Director of Community Relations at the UW (and a former Seattle City Councilmember), negotiate a deal for SHARE’s Tent City 3 to stay on the University of Washington’s Seattle campus for three months. SHARE insiders who were involved in bringing TC3 to campus told me that Hagopian pushed for this and was involved in every aspect of the negotiations.

- Winter 2017-2018: Hagopian, on behalf of the UW School of Public Health, accepts a “commission” to evaluate the LIHI/SHARE Licton Springs Village city-funded homeless camp, though it would be more accurate to say she offered the evaluation to SHARE free of charge. Hagopian and her class spend an estimated 1,440 hours taking surveys, analyzing data, and producing a summary report.

- March 26, 2018: Hagopian and her students present their evaluation at a community meeting in north Seattle. By this time, Licton Springs Village has been in operation for a year, and the purpose of the meeting is to take community input on whether it should be permitted for another year. Despite the general feeling of the neighbors in attendance that the Village should not be permitted for another year, Hagopian’s report strongly recommends that the project should be continued and that funding to SHARE be increased. Neither Hagopian nor her student Shaina Coogan disclosed to the audience their relationship to SHARE.

- September 26, 2018: Seattle’s Human Services Department announces its plan to close Licton Springs Village in March 2019 after two years of operation. Technically, the camp isn’t being closed early, but it’s the first time the City has closed any SHARE camp that was operating at taxpayer expense. In a Seattle Times article, HSD spokesman Will Lemke noted that the residents “weren’t getting into housing at the rate we wanted” and that the City had instituted a “performance improvement plan” for the site – a plan that did not envision SHARE’s continued involvement. To my knowledge, Dr. Hagopian had no comment on the City’s announcement.

- October 2018: SHARE is removed from the management of Licton Springs Village and replaced with Lifelong (formerly Lifelong AIDS Alliance). Lifelong reports to the Village’s Community Advisory Council on conditions at the camp, confirming HSD’s assessment that SHARE hadn’t been moving people into permanent housing and that SHARE had not kept adequate records of the camp’s operation.

- October 27, 2018: I send Dr. Hagopian a letter questioning the rigor of her Licton Springs Village evaluation study and the possibility for bias given her close relationship to SHARE. Her response is superficial and ignores key points I had raised, but she confirms, indirectly, that her study was not peer-reviewed or published. She doesn’t answer my question about getting (human subjects) review board approval but says that she followed “UW standard ethical protocols.” In terms of the study’s rigor, she says that her students used “systematic, conventional survey/evaluation methods, with continual faculty oversight.” She does not address the question of bias but says she is grateful to the folks at SHARE and LIHI for offering (!) the Licton Springs Village site so that her students could have a “hands-on learning opportunity.”

- Late March 2019: Following numerous complaints of abuse and mismanagement levied against SHARE by residents of the three camps the group still manages, a power struggle develops between SHARE and its fiscal sponsor, the Low Income Housing Institute. LIHI is the sole entity authorized by the City to manage these encampments and the City backs LIHI’s bid to remove the camps from SHARE’s control. Dr. Hagopian clearly and publicly sides with SHARE on the issue.

- March 31, 2019: Licton Springs Village closes for good. The remaining eight residents who couldn’t be placed are moved to another LIHI encampment. (Source: A Lake Union Village Community Advisory Council member.)

- April 8, 2019: LIHI takes control of the Othello Village encampment, ousting SHARE. SHARE boss Scott Morrow remains in residence. Residents begin to come forward publicly with complaints of coercion.

Equity Blinders

When I asked her about her about SHARE, Dr. Hagopian responded (by e-mail) that it was one of several community-based organizations she maintains a relationship with “so as to provide opportunities for my students to do projects.” But her relationship to SHARE clearly goes beyond what she needs in order to continue using them as a study subject. By her own admission, Hagopian is an advocate for SHARE, and her Licton Springs Village report was calculated to help an organization that she perceives as being on the side of the poor and oppressed. It was not designed to illuminate the truth, and it was certainly not in accordance with the School of Public Health’s standards of academic excellence. Consider this section from SPH’s Mission Statement page (captured in October 2018):

The first value listed under the Our Values section is Integrity, which SPH defines as adhering to “the highest standards of objectivity, professional integrity, and scientific rigor.” Has Dr. Hagopian followed that standard in her relation to SHARE? Did she follow it in producing her evaluation report or presenting it to a community meeting in the Licton Spring neighborhood?

The second item is Collaboration, which SPH defines as “nurtur[ing] creative, team-based, and interdisciplinary approaches to advancing scientific research and knowledge, and improving population health.” Has Hagopian followed that mandate? Did her evaluation advanced scientific knowledge or improve population health?

Diversity, another core principle, is defined as “embrac[ing] and build[ing] on diverse perspectives, beliefs, and cultures to promote public health. Hagopian can check that box. She has embraced “diverse perspectives” on truth.

Then there’s Equity, which SPH understands as a directive to “promote equity and social justice [whatever those may mean] in defining and addressing health and health care. We’ll give her that one, too.

Is it possible for these apparently conflicting principles to be reconciled, or do some have to compromised to satisfy others? Was that what Dr. Hagopian was doing in aligning herself with SHARE? What happens when the data you’ve gathered casts doubt on an organization that’s aligned with your social justice aspirations? Do you go with the data and let the chips fall where they may, or do you cull some of it to support your predetermined social justice conclusion?

As an academic, Hagopian’s not alone in her left-leaning worldview. She is part of broad turn toward the left in academia – and particularly within the social sciences – that is described in this Aero magazine article by Phil Magness:

Starting in the mid-1990s, the number of college professors who self-identified as conservatives or even moderates began to rapidly decline. In 1998, moderates made up 37% of the academy and conservatives made up 18%. In the most recent survey from 2013, moderates and conservatives dropped to 27% and 12% respectively. Meanwhile, self-identified liberals exploded in number. They sat at 45% in 1998, and have grown to 60% in the most recent survey. That’s a shift of over 15 percentage points away from conservatives and moderates and toward self-identified liberals. [ . . . ]As a recent article by political scientist Sam Abrams documented, some disciplines skew substantially further to the left than academia as a whole. While roughly 60% of all professors self-identify as liberals, that number tops 80% among English professors. History, political science, fine arts, and the other humanities and social sciences are all substantially more liberal than the academy as a whole. They have also shifted further left with the overall trends seen in the chart above.

And of course, a liberal swing for American academia as a whole will only be accelerated further in a “left coast” city like Seattle.

Hagopian’s dean and peers at the School of Public Health might not have known of her relationship to SHARE or how it would have compromised her research, but even if they did, it’s unlikely that they would have confronted her on it. Hagopian has become a force to be reckoned with at left-leaning UW. Her activities with BDS and military counter-recruiting are well known on campus. To our knowledge, she has never been censured by the University for her involvement in these causes. If she has, it hasn’t diminished her activism.

Conclusion: Soon, a reckoning?

Given the cloud of doubt growing around Scott Morrow and SHARE, Dr. Hagopian’s role in promoting the organization is increasingly troubling. If the worst allegations against SHARE turn out to be true, will Hagopian acknowledge her part? Or will she claim, like a Good German, that she didn’t know what was really going on inside the camps? How plausible would such a denial be, given that she and her students visited these camps often over the course of years? And what will the Hagopian’s colleagues at the School of Public Health say? Can they claim that they didn’t know what Hagopian was up to, even as she brought Scott Morrow and his tents onto University property? Perhaps they’ve all got equity blinders on.

Welcome to Seattle…

–By David Preston

*The improvement plan was never published.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank the following people for their research, encouragement, and advice: Nosilla Duke, Chad Smith, Christopher Rufo, Janice Richardson, and Amber Matthai. Special thanks to a person I’ll refer to only as The Marlboro Man.

Do you like this kind of independent journalism?

Then please reward it!

Afterword: They can do better

Regardless of what becomes of SHARE, the UW School of Public Health needs to review Dr. Hagopian’s activities, censure her, and tighten things up generally. Hagopian made several errors in judgment with the Licton Springs Village evaluation that could have been corrected with some timely oversight from her school’s dean or the dean of research at UW. Here’s an outline for an improvement plan:

- Hagopian should have included a bold disclaimer in the summary report itself, backed up by an oral statement at the meeting, that her Licton Springs Village Evaluation had not had a design review, did not include scientific controls, and was therefore not in the manner of a rigorous research study.

She presented her evaluation to a lay audience (the North Seattle Licton Springs community meeting) knowing that that audience would give it greater weight than it deserved.

- She should not have claimed that the evaluation was “commissioned” by SHARE, since it was not commissioned in any sense that a lay audience would infer. SHARE didn’t pay for the study, and they might not have even asked for it as a donation. What probably happened is that Hagopian volunteered hers (and the School’s) resources to SHARE to help ensure that Licton Springs Village would be permitted another year while also giving her a safe class project whose conditions could be controlled and whose results would be more or less predictable. If Hagopian didn’t want to mention that, she should have left the question of how the project came about to the audience’s discretion.

- The Executive Summary report should have sourced the crime data and other secondary data sources it relied on. The authors should have attended CAC meetings and talked with neighbors who were critical of the project so they could get a better sense of what crime data they should have been looking at and how to reconcile neighbors’ accounts with Seattle Police Department data. In a “limitations” section, they could have acknowledged that the crime data reporting was still underdeveloped and was in dispute. Dr. Hagopian’s comment to me that she was working with an unnamed “‘big data’ expert” was insufficient.

- De-identified interview samples should have been saved and transcribed. Otherwise, there is no evidence that any of the surveys were ever don or what they contained. Contact information for Hagopian or her department should have been included on the report with an invitation to readers to contact her if they had questions.

- Hagopian should have disclosed her longstanding relationship to Scott Morrow and SHARE as a disclaimer on the report itself and in an oral statement to the audience at the start of her remarks. She should have disclosed her student Shaina Coogan’s relationship to SHARE as well. At a minimum, Hagopian should have admitted that she had, in the past, petitioned the City Council to give money to SHARE and had been instrumental in bringing one of the groups “tent cities” onto campus.

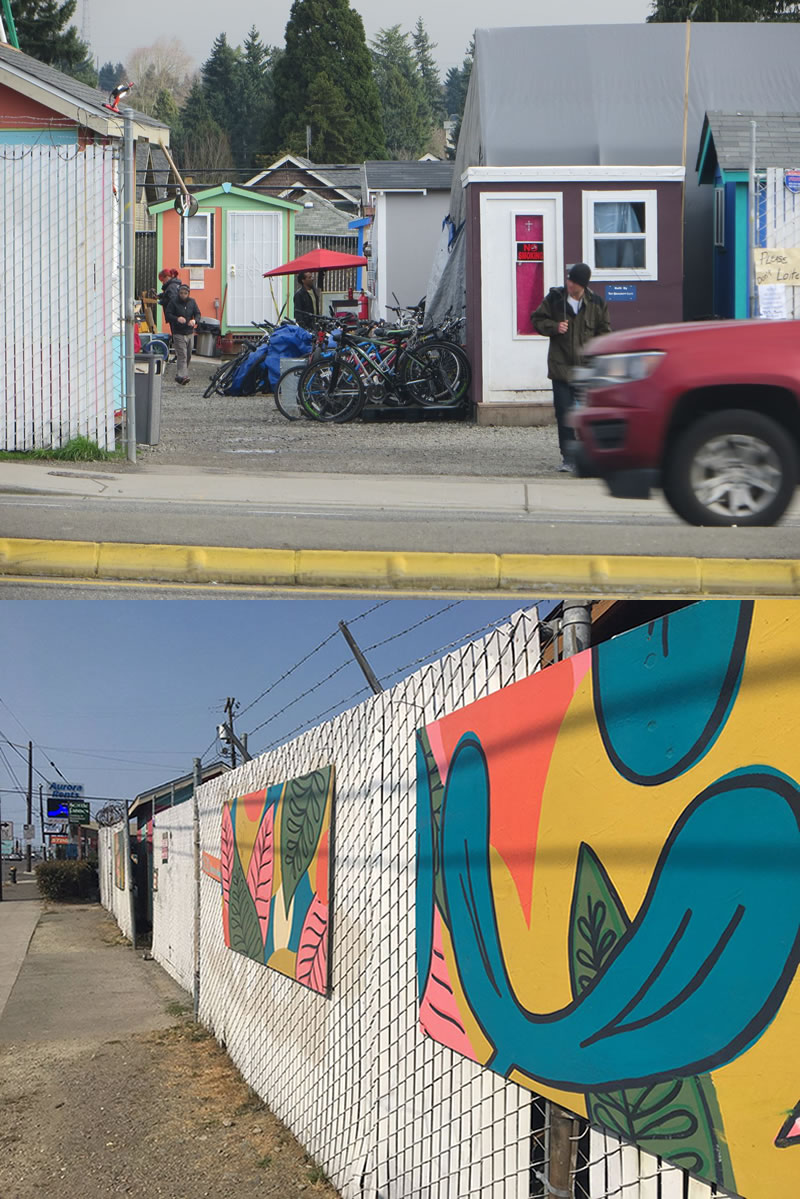

Bottom: The site as it looks today. Many “tiny houses” are still there, but the site is unoccupied. (Photo: KING 5)

Appendix A

CAC meeting minutes tell a different story

Every city-funded “tiny house village” in Seattle has an advisory body called a “Community Advisory Council” attached to it. These groups, which meet monthly near the village they’re connected with, are made up of 8 to 12 people recruited by the contracted operator, LIHI, to document the village’s progress at moving people into housing and to troubleshoot issues with the neighbors. If anything, CACs are sympathetic to SHARE’s interests and are generally willing to help the group put a happy face on any problems that arise. For instance, when crime goes up in the neighborhood around a village, as it inevitably does, the CAC can be relied on to assure neighbors it’s not the villagers’ fault and these are people coming in from elsewhere. CACs are not reliable sources of information about SHARE encampments; nevertheless, the meeting minutes of the Licton Springs Village CAC are useful for the discrepancies they reveal between Dr. Hagopian’s findings and what the camp staff themselves were reporting.

I’ve compiled all the 20 of the Licton Springs Village CAC’s extant monthly meeting minutes into a single document going backward from March 2019, the camp’s last month of operation. You can see that document here. You can also see the minutes posted separately by month on Seattle’s Homelessness.gov page here. I’ve highlighted sections of the minutes that cast doubt on Hagopian’s sunny evaluation or that are interesting for other reasons. Here are some examples:

► CAC Minutes for July, 2017. Note that it wasn’t until three months after the camp started operations, that the minutes record someone saying that “an accurate roster exists” (page 46 of the document). That suggests that for at least two months, SHARE didn’t even have a record of who was IN the camp. And this issue will come up later. In the same month, July 2017, the minutes speak of hunger in the camp: The impact of the shortage of food is that Licton Springs Village residents are “starving.” Individuals who are older, lack proper nutrition and who also may have medical issues and dietary needs are particularly vulnerable. The difficulty dealing with residents and providing other services when the resident is confronting hunger was mentioned. (Page 45.)

► August 2017. Nearly every month has complaints from the neighborhood residents or businesses about people camping and loitering in the vicinity of the Village. This comment is typical: A lengthy discussion followed regarding the dilemma of the outside encampment street people, as they are not seeking, nor are interested in receiving assistance. They just want to “hang.” The major complaint within the neighboring community is not about the tiny houses. Justifiably, the problem is the complaints from neighbors about the street people predominately on Nesbit Street between 85th and 90th. (See pages 38 and 40.)

► November 2017. There’s a note that a group of UW students will be doing a study on the camp (page 34.). The minutes don’t mention Dr. Hagopian by name or her relationship to SHARE director Scott Morrow. Perhaps no one at the CAC knows about Hagopian’s involvement.

► January 2018. Here we learn that Seattle’s former “homelessness czar” George Scarola “never specified what the [Licton Springs Village] benchmarks were beyond exits to permanent housing,” although he was “solid in recognition that the village has exceeded expectations.” (Page 32.) Hagopian’s evaluation is mentioned for the second time, on page 31, but is referred to as a study by the “UW Department of Health”.

► March 2018. The sloppy method by which exits to housing are tracked is evident here. In the Report on Village Operations section (page 29) it’s recorded that there are “not many exits to housing.” How many is “not many”? What was the target? –We’re not told. Under the Case Management Report section of the same month (page 30) it says that “a few residents have exited into housing recently” but again, it doesn’t say how many or what is meant by recently. Nor does it specify what type of housing the residents exited into or how long they would be tracked following that. Presumably this “information” was provided by the two professional case managers from LIHI who were in attendance at the meeting, Sherry Sternhagen and Charlie Johnson. ►Elsewhere in the March 2018 minutes, it states that Hagopian’s study is nearing completion. And there is a preview. Hagopian’s “#1 finding,” which was shared with someone from the CAC in advance, is that the City should give more money to SHARE. The #2 finding was that there was no change in “crime statistics” for the neighborhood. The results must have been pleasing to Ms. Hagopian’s friend Scott Morrow, though they surely weren’t a surprise.

Hagopian told people running the Licton Springs Village that her #1 finding was that the camp needed more money. This is exactly what her friends at SHARE had been claiming from the beginning. At this time, the City was paying LIHI over half a million dollars a year to run the camp. The tiny house structures, food, and most others supplies were provided free of charge. So where was that half a million dollars going?

Nowhere in the any of the meeting minutes that speak of this study is Dr. Hagopian’s name used, and nowhere is it mentioned that Hagopian is an old friend of Mr. Morrow’s. It’s always just the “UW Study.”

► April 2018. On March 26, 2018, there was a community meeting to discuss Licton Springs Village. This was the meeting at which Dr. Hagopian presented her report. At the meeting were CAC members, SHARE staff, LIHI staff and Licton Springs Village residents. But there were also news reporters and a number of neighbors who were critical of the Village. This was a watershed moment for the Village and meeting minutes in subsequent months show a marked change. There’s more discussion about whether the village is succeeding at getting people into housing, about the crime rate (or perceived crime rate) in the neighborhood, and about the relationship between SHARE and LIHI. At the April 2018 CAC meeting, LIHI’s Josh Castle mentions a second target for the camp: “number of homeless individuals who had their emergency or immediate shelter needs met.” The target was 75, according to Castle, and claimed that Licton Springs Village had exceeded that target by four homeless individuals (page 27). Castle also mentions exits to housing, which he claims were 13 out of 27 total exits (or 48%) for 2017, which was “very close” to the target of 50%. He goes on to say that the camp is underfunded by the city to the tune of $191, 758. This echoes the Hagopian study’s “#1 finding” that the City should be ponying up more money. ► There’s an interesting note from the same meeting on page 25: Crime was discussed in context of recent news articles and information being presented by the public. The crime studies and reports are conflicting and often are being prepared and/or interpreted to support a particular narrative, whether for or against the encampment. –Here, someone (we don’t know who) is saying that there are conflicting crime studies and reports and that Ms. Hagopian’s study is not necessarily definitive but may have been prepared to support a pro-encampment narrative. ►On page 24, Michelle Marchand, co-director of SHARE, announces that the City has asked LIHI to give them a “performance improvement plan” for the Village, due in two weeks. Among the key items mentioned in the City’s letter were security, improved opportunities for village residents during day hours, aesthetics (e.g. village cleanliness and property perimeter), and professional staff service provision.) The City’s view of the camp’s performance clearly does not correspond to Dr. Hagopian’s. Nowhere does it suggest that the City is considering giving more money to the camp’s operator, as Dr. Hagopian recommended.

► May 2018. Another reference to “not a lot of exits lately” (page 23). In other words, people aren’t moving out of the camp into permanent housing. Some discussion about whether the camp’s permit will be renewed for another year. Someone wonders: Who here understands the process by which the renewal is continued? And later: Between the two organizations [SHARE and LIHI] doesn’t someone know about the exact legal process?

► June 2018. As time goes on, it becomes clearer that the camp is operating without benchmarks or metrics. A community member named Sharon Holt spoke of frustration in getting information from the city and from LIHI about Village effectiveness. She and other neighbors would like to see numbers that show the accountability of the Village. It is hard to get quantitative data on numbers served and the results of their stay in the Village. It was suggested that Josh Castle attend the next meeting and come with data (page 21). Meanwhile, former Homelessness Czar George Scarola is focused on damage control (He has a special focus on neighborhood relations with a goal of creating a more positive image of Licton Springs in order to ease the way to open more encampments) and two CAC members, Elizabeth Dahl and Marni Campbell, principal of the nearby Robert Eagle Staff Middle School are writing an op-ed piece to be sent to local media in order to “address misconceptions” about the Village (page 20).

► July 2018. More talk about difficulties with “pop-up” homeless encampments around Licton Springs Village. LIHI’s Josh Castle suggests that CAC members go to an upcoming King County Council meeting to advocate for affordable housing programs that will ostensibly benefit LIHI. Although there are no Licton Springs Village residents at this meeting, they will likely have been encouraged to attend this meeting too. Compulsory political activism has been a frequent charge against SHARE. (See also here.) Since Castle represents a City contractor, his remarks may have violated City policies about conflict of interest as well.

► August 2018. Six people exited to hotels. No one exited to housing. Information from Seattle Police Department representatives: Increase in calls near village, on views (seen by SPD), and [in SPD’s opinion this is] due to increase in homelessness overall. (Page 16.) Also: N precinct sergeants: neighborhood has changed, increase in calls around the village. Trying to have officers nearby more often. SPD working with the village to address village issues. (Page 15.)

► September 2018. SHARE’s Michele Marchand announces the City’s intention to close Licton Springs Village and direct LIHI to subcontract with someone other than SHARE to manage the Village in the interim, an outomce she considers “unacceptable” (page 12.) ► Much discussion of the failure of SHARE and LIHI to provide case management services. LIHI has never had an “on-site point person” at Licton Springs Village (page 13.) There has been a lack of case management. The city is holding LIHI accountable for the gaps (page 13). ► Discussion of who is more to blame for the problems, LIHI or SHARE, though all involved saw the lack of provision of case management as missing from the start along with a lack of funding. The model provided by LSV works when it is fully funded. Case management should be made a priority. (Page 13.) Note that while Dr. Hagopian’s study did call for more funding, it did not conclude there was a “lack of provision of case management.” ► One resident is expected to get into housing but isn’t there yet (page 14). This is the last item on the agenda and it is a brief one. It seems like an afterthought.

► October 2018. Lifelong takes over direct management of the camp and reveals that SHARE was mismanaging the operation. From page 10: One concern the City is finding is matching the Village Roster with who physically lives there. The City is still trying to answer the question of who really lives in the Village. [ . . . ] Lifelong was also finding that residents thought the encampment was a permanent place to reside. The residents were told previously by SHARE/WHEEL that they did not need to leave the encampment and that they did not need to be engaged. [ . . . ] LIHI mentioned that it really tried to engage with SHARE/WHEEL but it was really difficult to do so. –So we have two non-profit organizations (LIHI and Lifelong) and the City of Seattle who are saying that SHARE was not getting residents into housing and may not have even known who was living at the camp. How does that square with Ms. Hagopian’s evaluation?

November 2018. Apparently the City still doesn’t know how many people are moving from the camp into permanent housing. There is a need to report transitional and bridge housing, in addition to permanent housing, to City Council in order for them to have a clearer picture of the successes in placement of homeless individuals. (Page 7.)

There was no CAC meeting in December. The minutes from January through March of 2019, when the camp closed describe an orderly process of Licton Springs Village winding down.

Appendix B: An activist’s activist

A Google search on Amy Hagopian + Seattle + activist produces thousands of hits. Here are just a few articles on political movements Dr. Hagopian is involved with. Some of them are about her. Some are by her. With the exception of her connection to SHARE, there’s no apparent conflict between Hagopian’s duty as a researcher and her private life, though we might expect her to be a little extra mindful in her relations with her Jewish students or those employed by the U.S. military. A clear conflict arises in regard to her work with SHARE, however, and while university professors shouldn’t be required to check their social conscience at the door, they should at least seek guidance and supervision wherever a potential ethical conflict might affect the integrity of their teaching or research. Did Hagopian do that? Apparently not.

Boycott-Divestment-Sanctions (of Israel)

Mike Report Blog: Husky Mom: “I was accosted by UW professor at anti-Israel lecture.”

SocialistWorker.org: Respect the BDS Picket Line

Jerusalem Post: Pro-Israeli activists defeat anti-Israel resolution on Palestinian Health Issues

South Atlantic Quarterly: Policing the Divestment Debate

Counter-military Recruiting

New York Times: Growing problem for military recruiters: Parents

Book: Counter-Recruitment and the Campaign to Demilitarize Public Schools by Scott Harding and Seth Kershner (several references to Hagopian)

MyNW.com: UW prof compares military recruiters with child sex predators

Peace and Miscellaneous Activism

Crosscut: Why some UW professors want a union andhttps://crosscut.com/2015/11/uw-union-push-pits-empowerment-vs-excellence others resist one

What’s the solution to homelessness?

If there’s anyone who should receive kudos for good journalism, it is YOU. A most excellent, well researched and documented piece of journalism.

Thank you for your time and effort to expose this part of the homeless industrial complex, which is not a solution for homelessness.

Thanks for your publication. One other thing is the fact individual American states have their particular laws which affect house owners, which makes it quite hard for the our elected representatives to come up with a different set of recommendations concerning foreclosures on property owners. The problem is that each state has own laws and regulations which may interact in a damaging manner in regards to foreclosure insurance plans.

I just finished reading your feature-length article, “The Academic”.

Wow, exhaustive, humorous (“..being a Good German..”), and damning for this Academic. Your team’s sunlight shone bright light on her hypocrisy. It may be difficult for her to claim innocent intent after your report. I wonder how much more carefully she’ll tread in her activism and public statements on these issues moving forward?

I wonder what it felt like to (metaphorically) stand in public in her underwear reading the revelations you investigated? Would she feel any remorse at her actions? Or simply lash out, or quietly skulk away?

Shameful, selfish and misguided behavior by her and those she influenced. Cult-like SHARE. I’m so puzzled at Scott Morrow’s apparently charismatic appeal. Feeding their personal agendas and manipulating the issues rather than dealing with the problems at hand.