November 3, 2016

Warning: Disturbing content.

Narrative

In late 2012, a just-turned-16-year-old girl whom I’ll call Angel was staying at the Nickelsville homeless camp in Seattle’s Highland Park neighborhood, along with her mother and two younger siblings. One evening, she and two older male campers went across the road to a convenience store where one of the men bought some beer. The three of them then went under a nearby bridge to drink it. Angel soon got drunk, and one of the men then forced her to perform oral sex on him. He also tried, unsuccessfully, to vaginally rape her. Shortly afterwards, Angel returned to camp, still in an intoxicated condition and covered with dirt from being forced onto the ground by the man who’d assaulted her.

Showing up drunk at the Nickelsville camp was a “bar-able” offense, meaning it was one of the many things a camper could be evicted for. Angel also had a reputation around a camp as a troublemaker, which did not argue in her favor. The Executive Committee of the camp held a meeting and voted to bar Angel from the camp, along with her mother and siblings. However, Angel, not wanting to make trouble for her family, volunteered to leave camp on her own, which her mother agreed to. After being separated from her mother and evicted from camp, Angel took up with a much older man whom I’ll call Mark. Mark was a former employee of SHARE, the organization that ran Nickelsville. He was also a recovering heroin addict who was “chipping” (using heroin recreationally) and struggling to make support payments for a child he’d had with another woman. During the time Mark was with Angel, they both used heroin, but how often I don’t know.

The Nickelsville site in Highland Park, where Angel stayed with her mother. Looks like a great place for kids. Photo: Kevin R. McClintic

At first the couple were staying in motels. When their money began to ran out, they moved to a greenbelt up the street from Nickelsville where other acquaintances of theirs were living. These were people who’d also been evicted from the camp or who had left on their own.

Somewhere during this time, Angel became pregnant. At that point, her life became focused around giving up heroin and keeping her baby.

During first few months of her pregnancy, Angel maintained a loose connection with the camp and she and Mark would show up there from time to time to get help from friends who were still there. But this stopped after there was a violent confrontation between Mark and the camp boss. Staff at Seattle’s Union Gospel Mission were alerted that Angel was missing and endangered, and they sent search parties to the greenbelt looking for the girl, but she actively evaded them. Authorities at Nickelsville had warned Angel that if she was found, CPS would take her baby away, so she kept away from people who might have helped her.

When Angel was 4-5 months into her term, two female friends of mine contacted her through a third party. My friends spent considerable time with her over the next few months, taking her to well baby appointments, giving her a bit of money and a lot of emotional support. Angel told them her story and they relayed it (with Angel’s permission) to me. Meanwhile, I talked with my contacts at Nickelsville who would not confirm or deny the rape but did confirm that (a) Angel had lived in camp with her mother and siblings, (b) she was expelled from the camp, by herself, while her mother and siblings stayed. My contacts also acknowledged that Angel was considered a problem by the camp management and some campers. The camp authorities may thus have been looking for an excuse to expel her and they found it when she returned to the camp one night drunk.

Since she was afraid of losing the baby, Angel waited a long time before going in for her first “well baby” check-up and missed or cancelled several appointments after that. At one check-up, Angel flunked a urinalysis for heroin and since she knew that midwives are mandatory reporters, Angel reckoned that it was just a matter of time before CPS swooped down and put her on probationary monitoring. Shortly before delivering, she left the state with Mark and went to an undisclosed place in another state, where she claimed to have friends. Although we heard back from Mark occasionally after the baby was born, we eventually lost track of her.

We’re praying for her and her child (now 2 years old) but we know the odds are against them. Her life may be salvageable, but her childhood? No. That’s over. It ended the day she was raped, at a homeless camp . . . where she never should have been in the first place.

Barefoot and pregnant, and only 16. Angel and Mark hooked up after they were evicted from Nickelsville.

Aftermath

My friends and I went to the police within days of hearing about Angel. We pleaded with a Community Service Officer (CSO) at the SW Seattle Police Precinct, pressing him to take action. But he declined, saying he couldn’t get a conviction unless Angel came forward voluntarily, and if he couldn’t get a conviction, why bother doing anything? The part about the conviction was true enough: the age of consent for sex in Washington state is 16, so unless Angel had pressed charges, neither the sexual assault under the bridge nor the sex she had with her boyfriend would have been considered rape under state law. Angel wasn’t likely to contact the police on her own either. Here she was, this confused, lost kid. The only thing in her life that didn’t suck was this baby on the way, and based on what the Nickelsville people had told her, she thought she might lose that, too . . . if she went to the cops. She was also reluctant to testify against the man who had assaulted her outside of the camp, she said. She told my friends that she felt sorry for him and didn’t want to get him in trouble.

The SW Police Precinct building was just a mile up the road from Nickelsville when Angel was there. Police there knew what had happened to Angel, but they declined to pursue Angel’s case or exert any pressure on Nickelsville, saying they could only act if she came them. Photo: HBB Landscape Architecture.

I knew the CSO officer had a relationship with the camp authorities and had visited the place several times. I urged him to set aside the rape question and go down to Nickelsville anyway, to ask around about what happened. I explained to him that just his presence there would put the camp bosses on guard and maybe discourage them from inviting any more children in. Again he refused. I got the impression that if it were up to him, he would have gone down to camp and would have approached Angel about what had happened, but that he was forbidden to do that for political reasons. He didn’t say it in so many words, but he gave me to understand that SPD had been directed to take a hands-off approach to Nickelsville. Which didn’t surprise me in the least. When you consider the deep and long-standing political ties the Nickelsville management has at City Hall, ties which I detail in this article, the picture becomes even clearer.

The cop we spoke with was sympathetic to our concerns, so I’m not going to single him out here. I just wish he’d shown a little more courage . . .

How could this happen?

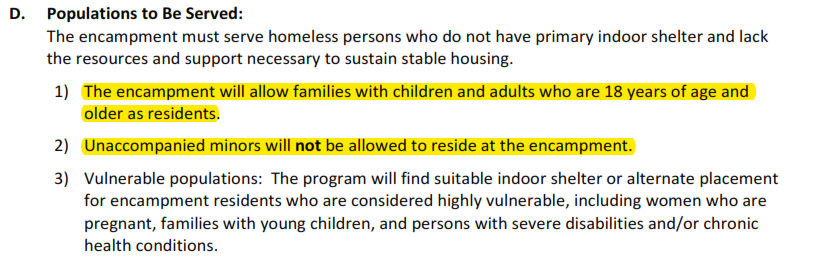

One would think that the civil authorities (police, CPS, public health nurses) would do everything in their power to keep children out of homeless camps, but such is not the case. In fact, Seattle has contracts whereby the City pays SHARE – the same group that ran Nickelsville – and its partners to operate three camps, all of which accept children. (See contract document here.) In the Seattle model, camps are seen as a good option for families with children because of the assumption that the mothers who show up there would otherwise be living on the streets, or in cars, where they would be at even greater risk. Has this assumption ever been tested? Not to my knowledge.

A Nickelsville flyer from 2013 entices parents with images that appeal to children.

I don’t know the number of family shelters currently available citywide. I do know, however, that providers of low-income housing bump homeless parents with children to the top of the waiting list. And in the meantime, the City offers motel vouchers for families waiting to get into shelters or transitional housing. I talked to several Seattle councilmembers and was told that homeless people – even those living on the streets and in the woods – frequently decline motel vouchers and City services that are offered to them. I also know about a woman who stayed with her teenage son at Nickelsville for about two years. I’ll call her Roxanne. Roxanne was offered housing repeatedly but turned it down. According to camp volunteers who knew her well, Roxanne was a methamphetamine user and a prostitute, and would use her motel vouchers to ply her trade with fellow campers. Her picture was familiar from news stories on Nickelsville, and she came into contact repeatedly with social workers and others who offered her a way out of camp. But she consistently declined. Roxanne’s behavior was not typical of a parent at Nickelsville, but it is not uncommon for people – even vulnerable ones – to stay in homeless camps when offered better choices. I worked with another young woman at Nickelsville who repeatedly turned down offers of housing and other assistance from good-hearted people I tried to put her in contact with. She trusted me, she said, but no one else. She was an untreated psychotic who was afraid of being forced to take medications.

The SHARE organization and its supporters claim that they don’t have the heart to turn families away from their camps. But they go further than just not turning families away. They advertise for them. No sooner had SHARE set up its Nickelsville camp in my neighborhood than the camp management, with the blessing of the City Council, began enticing parents to bring children there to live. In their first summer, they used a neighborhood blog to promote a fundraiser for playground equipment and regularly solicited donations of toys, school supplies, and children’s clothing. In response to this Pied Piper call, Angel’s mother turned up one day with her three children and was welcomed with open arms.

The “playground” at Nickelsville in Highland Park. Photo: David Preston

If you’ve spent time in these camps, it’s easy to see why they like kids there. Children – especially pre-teenagers – give the place a warm fuzzy feeling, making it feel more like a home and taking the edge off the general misery. Kids are good for the bottom line, too, because they’re great little fund-raisers. When friendly reporters come by, which they always do around the holidays, the camp bosses push the mom and kids in front of the cameras to make a pitch for donations. See a typical example here. The reporters get a warm, fuzzy story, and the bosses get to sit back and wait for the donations to come rolling in.

Conclusion:

Homeless camps aren’t safe for kids and can’t be made safe

While volunteering at the Nickelsville camp and visiting others, I have seen children of all ages living in close proximity to drug addicts, violent felons, and untreated psychotics. That such people should be living there is inevitable, since, in addition to being a refuge for a few people between jobs and apartments, these camps are a more or less permanent stop for folks who can’t find regular housing. Felons and addicts have a hard time getting a job and an apartment because of their record or their behavior. Psychotics often get kicked out of housing because they are perceived as a threat by others. In a system where the safety net is already overwhelmed, people with these severe impairments are bound to form a large percentage of the homeless population. Perhaps some kind of camp system would work for them, but there’s no way such a camp could host children safely.

Several hundred dollars were raised to pay for this swing set at the Nickelsville homeless camp. I never saw any children using it, but it was still doing it’s job attracting children to the camp. Photo by Kevin R. McClintic

Unfortunately, Angel’s tragedy is not a fluke or a one-off kind of thing. Over the years, I’ve been contacted many times by people with information about children being neglected or abused at these places. Last month two of my other friends discovered three three young children living under the supervision of a heroin addict in the squalor of a camp near my house. The camp was there with the blesing of the Mayor and City Council. Moreover, there is reason to believe that Child Protective Services have been instructed, like the police, not to intervene. When I notified CPS of children at a camp in the suburb of Skyway, a caseworker told me, curtly, that “it’s not a crime for a mother to be homeless.” She told me that CPS needed to have solid evidence that children were being harmed before they could intervene. (I guess raising your children in a squalid trash heap among drug addicts and psychotics is not evidence of harm in CPS’s eyes.)

Mayor Ed Murray travels the globe promoting gay rights. However, when my friend asked him to respond to a child rape here in Seattle, he said there was nothing he could do. See more below. Photo: Seattle Channel

Though Angel’s situation wasn’t the worst abuse I’ve heard of, her case is special, because it points up most starkly the cruelly deceptive nature of the “camps are safe for kids” message SHARE and the Council have been sending out. Angel’s mother felt that she and her children were safe at Nickelsville. She might have thought that as long as she was nearby, Angel would be safe. But a 16-year-old has considerable freedom of movement, and her mother couldn’t watch her all the time. That Angel was raped was bad enough. But the danger was compounded when the camp authorities deliberately separated her from her mother. Abandoned to her fate, Angel took up with a much older man outside the camp who had sex with her and got her hooked on heroin. After she became pregnant Nickelsville staff put her and her baby in even greater danger by convincing her that if she went to the authorities she’d lose her baby.

Seattle’s current contract with SHARE and its affiliate allows children at three homeless camps around the city. [Click to enlarge.]

Story by David Preston

Postscript

Below is an e-mail exchange between then Senator Ed Murray’s aide Scott Plusquellec and my friend, who had written Murray after she met with Angel and heard her story. After contacting the police and several other agencies, she reached out in desperation to Mr. Murray. This was actually the second exchange between them. As you can see, Murray’s aide ignores the specific allegations of child rape and abuse and frames his answer in terms of government funding for the Nickelsville camp. Murray’s response was typical of what we heard from the police, from Child Protective Services, and others. “Nothing we can do,” they’d say. “It’s out of our jurisdiction.”

Ed Murray has since become Mayor of Seattle, but his position with regard to the camps hasn’t changed. He still supports allowing children to be there.

I remember years ago, you saying these are not good places for kids. I believed you but then years later, I heard about stories like the one above. Thanks for shedding light on this whole dysfunctional Share/Nicklesville/City of Seattle thing.

Great job again david