November 7, 2017

The Seattle Ethics and Elections Commission enforces the Seattle Code of Ethics, which was designed to keep Seattle government honest by applying fines and other penalties to elected officials, candidates, and city employees who violated the rules of the Code. Unfortunately, the Commission has few tools at its disposal, and the ones it does have, it uses timidly. Its members are appointed by some of the same officials it is tasked with policing, and in some cases, which I’ll discuss below, it is staffed by these officials as well. The Commission is necessarily a political creature, and it is only as honest as the political culture in which it operates. When that culture is honest and peer pressure works to enforce normative behavior, the Commission appears to be working to keep everyone honest. As the culture degrades and becomes increasingly dishonest, the Commission lowers its standards accordingly. Where it blessed and sanctified an honest culture before, it now does the same for a corrupt one. And what else can it do? By itself it is powerless to change the course of events.

I’ve followed the doings of the Commission for the past two years and have noticed that when it comes to complaints against City employees and candidates, penalties are light, even when the complaint is proven. A complaint I made against City Council candidate Lorena Gonzalez was affirmed at a hearing in early September. The Commission acknowledged that Gonzalez – who was trying to be certified for Seattle’s Democracy Voucher Program – had wrongly claimed that she’d attended three public forums during the primary. But they declined to impose any penalty on her, reasoning that since the program was new, and since it was complex in some of its aspects, Gonzalez should be not be held to the letter of the law. A week later, the Commission qualified Gonzalez to participate in the Democracy Voucher Program, thereby entitling her to receive some $140,000 worth of vouchers she’d collected in the taxpayer-funded campaign financing program.

A Pattern of Wrongdoing

In her initial complaint response, Gonzalez claimed that there were only five public forums offered during the primary season. She then gave reasons, which the Commission found plausible, why she could attend only one and couldn’t make any of the others. When she promised to do better in the future, the Commission took her at her word.

Gonzalez failed to disclose that there were at least four, and as many as six, additional public forums to which she was invited during the primary and which she did not attend. Based on that, I appealed the Commission’s initial ruling on the grounds that Gonzalez had materially misled the Commissioners in her complaint response and in her testimony to on the day of the hearing. Below is a document comparing Gonzalez’ testimony to the Commission to the facts of the matter.

Gonzalez failed to disclose that there were at least four, and as many as six, additional public forums to which she was invited during the primary and which she did not attend. Based on that, I appealed the Commission’s initial ruling on the grounds that Gonzalez had materially misled the Commissioners in her complaint response and in her testimony to on the day of the hearing. Below is a document comparing Gonzalez’ testimony to the Commission to the facts of the matter.

The first page of my appeal shows the forums that Gonzalez disclosed to the SEEC vs. the actual forums available. The second page shows the general election forums that occurred after the complaint was filed but before Gonzalez appeared before the SEEC the first time to explain her forum attendance. She didn’t mention these general election forums in her response to the SEEC, and, strictly speaking, she didn’t need to, since the matter at hand was her attendance at primary forums. However, I’ve included them to show that Gonzalez non-attendance at forums was part of a pattern:

SEEC_Gonzalez_Complaint_Appeal_Hearing_c

Note: This list was compiled by Ms. Gonzalez’ challenger in the general election, Pat Murakami. Gonzalez, Murakami, and I were all candidates for Council Position 9 in the primary election. The two candidates in the general are Gonzalez and Murakami.

No Lorena, No Forum

The table shows that there were as many as three forums that were cancelled because Gonzalez refused to attend. Jeanette Kahlenberg of the League of Women Voters organized forums for the Position 8 candidates and Mayor’s race at the Horizon House apartment complex in downtown Seattle in June. Both events were successful and well attended and there is no reason to think that a forum for Position 9 candidates wouldn’t have been equally popular. Kahlneberg told me that she tried to organize a forum for Position 9 as well, but when she e-mailed Gonzalez to see if she’d be interested, Gonzalez didn’t respond. So she dropped the idea. When I asked her why she dropped it because one person wasn’t going, Kahlenberg explained that Gonzalez, as the incumbent, was the star of the show. And without the star, the show couldn’t go on. Gonzalez’ refusal to respond to Kahlenberg’s invitation meant that not only would she, Gonzalez, not be meeting with the public at Horizon House, the other Position 9 candidates would not be there either, because there would be no forum.

As the table above shows, there were two other organizations (Growing Seattle and Wallingford Community Council) that hosted forums for both Council Position 8 and Mayor but did not host a forum for Position 9. We have every reason to believe that the Horizon House scenario repeated itself with them. It seems likely that in those cases the forums would have been held if only Gonzalez had agreed to attend, but since she didn’t, the forums were dropped. If that is the case, then not only did Gonzalez deprive the public of meeting her, she deprived it of seeing her competitors as well. This is precisely the opposite of the voucher program’s intention. And yet still, somehow, Gonzalez was approved to participate in the program.

Swung Jury

On October 5, I collected the new information I’d gotten from Ms. Murakami and requested an appeal of the Commission’s initial ruling on my complaint. Read the appeal document here.

The commissioners heard my appeal on Thursday, October 19 at 2:00 PM at their office in the Seattle Municipal Tower. Commission Chair Eileen Norton invited me to present my appeal, but she cut me off several times and didn’t let me finish my account of what Ms. Kahlenberg had told me about the planned Horizon House forum. “Mr. Preston, I told you at the first hearing that no one is required to hold a forum” she interrupted (I’m paraphrasing). I explained that this matter went to the truthfulness of Gonzalez’ testimony on the initial complaint and that it showed a pattern and deception, but it bounced off her. She and other commissioners present in the room barely glanced at the new material I’d brought with me (see the Forum Appearances table above), and the three commissioners who were attending the hearing by telephone could not even see it. I got the impression that none of them had read the complaint appeal document I’d submitted some two weeks earlier. The few questions they asked suggested that they hadn’t.

The Democracy Voucher Program might be complex in some of its parts, but its definition of a “public forum” is clear and concise. and printed right on the one-page form Lorena Gonzalez signed attesting that he had attended three such forums. The form also said that she’d be fined and/or disqualified from the program if she failed to comply with the program’s terms. Gonzalez did fail to comply, but the Ethics Commission did not fine her or disqualify her. They didn’t do anything to her. See the full form that Gonzalez submitted here.

Ms. Norton then called for the Commission to dismiss my appeal peremptorily. She said that she wasn’t going to consider any of the new material I’d submitted and that she and the Commission had decided the matter at the first hearing. The Voucher Program was new and confusing, she reminded me, and she was still convinced, as she had been at the initial hearing, that Gonzalez was doing her best to try to meet the requirements. Following their habit, none of the other Commissioners bucked Norton. They voted unanimously to dismiss my appeal, without any deliberation.

Ms. Norton’s conclusion was either disingenuous or naive. The evidence I presented shows overwhelmingly that not only did Gonzalez lie on her self-report forum, she lied repeatedly and materially in her defense of her behavior to the Commission. As I’ve shown, Gonzalez was invited to between seven and ten legitimate public forums during the primary. She was only required to go to three to qualify for the Democracy Voucher Program. And yet, in the end, she made it to only one. But despite my well-documented complaint and appeal, the Commission qualified Gonzalez for the Voucher Program anyway, claiming that she’d made a good effort, and that was enough for them.

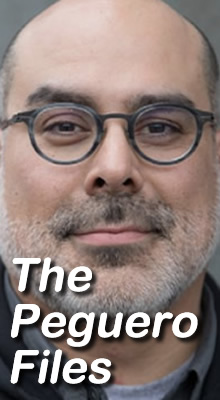

The Commissioner and the Councilmember: Eileen Norton (left) chairs the Seattle Ethics and Elections Commission. Councilmember Gonzalez voted on Norton’s appointment and served on the Commission for two years herself, leaving a short time before Norton was appointed.

What went wrong and how we can fix it

Justice was not done here. Lorena Gonzalez, an insider, took a program designed to level the playing field between insiders and outsiders, subverted it, and used it to give herself an unfair advantage. The Ethics Commission was supposed to keep this kind of abuse from happening, but the Commission repeatedly failed to do its job, letting Gonzalez get away clean. Why did this happen and what can be done to make sure it doesn’t happen again?

A dog in the fight – When the Voucher Program was approved by Seattle voters two years ago, the Ethics Commission was tasked with drafting rules for implementation of the program, so its organizational ego was likely engaged in the Gonzalez case. My sense, listening to the testimony and deliberations, is that the Commissioners were loathe to admit that the rules they had drafted for the Democracy Voucher Program were being flouted so soon, and so flagrantly, by a candidate. During the initial complaint hearing, Commissioner Norton said repeatedly that the program was new and complicated and that both the candidates and the Commission were still figuring it out.* Given that the Commission itself had drafted these rules, it should not have been tasked with enforcing them as well, at least not until the rules had stabilized and there had been sufficient turnover at the Commission such that no Commissioner who had participated in their drafting would have been sitting in judgment of someone who was accused of violating them.

Court of first and last resort – In jurisprudence, the review process ensures that the parties get a fair and thoughtful hearing. It also keeps lower courts in line, keeps them from ruling capriciously. The idea is that if you don’t prevail at one level, and you feel strongly that the Court’s decision was flawed or based on insufficient or improper evidence, you may appeal the decision to a higher authority, based either on new information that has come to light or on a reasonable claim that the lower court used a faulty argument to decide the case. The model works well, but only when there is a higher authority to appeal to. Where the higher authority is the same as the lower one, the system is useless. This is a thus a flaw with the Ethics Commission’s appeals process. Complainants (and likewise respondents) should be able to appeal their case to a higher authority; they shouldn’t be put in a position of trying to convince the Commissioners that they erred the first time around. Commissioners are human and humans don’t like to admit when they’ve made a mistake.

Good ole girls club – While presenting my case to the Commission and observing the Commissioners quiz Ms. Gonzalez, I perceived that they felt sorry for her and were determined not to impose even a nominal penalty upon her. It later occurred to me, as I explored Gonzalez’ relationship to the Commission further, that they might have viewed her as a colleague or peer and not someone they could stand in judgment of, or punish. Three of the seven Commissioners are nominated directly by the City Council and all nominees are confirmed by it. Gonzalez has been on the City Council since 2015, and so she would have voted to approve Ms. Norton’s reappointment to the Commission in 2017 as well as that of any other commissioners who were nominated during Gonzalez’ tenure. And here’s an even more interesting fact: Gonzalez herself was on the Ethics Commission for more two years, between 2012 and 2014. She resigned her appointment to become Ed Murray’s legal counsel just six months before Ms. Norton came on board. Given Gonzalez’ close relationship to the Commission as a body, it is easy to see why they might have been predisposed to go easy on them. She was, after all, one of them.

Wrong tool for the job

The Seattle Ethics code is just that, a code. It is not a law. A law is clear and requires little interpretation to determine if it has been broken, once the facts are known. An ethics code, by contrast, is fuzzy and amenable to interpretation, even when the facts are known. The Ethics Commission is a quasi-judicial administrative body, not a court. Its task is to interpret and apply this fuzzy ethics code, and although it has the power to sanction, it does not have the power to enforce. The Commission, being cognizant of its limitations, tends to go light on violators.

Commission Director Wayne Barnett is not one of the Commissioners himself. He serves in a support role. Earlier this year Barnett sent me, at my request, a list of all fines the Commission has imposed on City employees since its creation 18 years ago.

The all-time heaviest fine, for $14,750, was imposed seven years go. That was one of the most straightforward cases the Commission ever handled. A City trucking inspector had been giving private inspections to trucking companies for a fee, allowing them to avoid costly penalties and repairs. The Commission went easy on the moonlighting inspector, fining him just $5,000 net. The other $9,750 rest was money he made from his illicit inspections and was forced to surrender.

The next heaviest fine – which is not included in Barnett’s list but is described here – was imposed in 2016 on the head of Seattle’s Department of Transportation, Scott Kubly. Kubly failed to disclose to the City his prior relationship to a bike-share company when he was hired. This was material because Kubly was later influential in persuading the City to buy the company, a clear conflict of interest. (See more on that story here.) Kubly was initially fined $10,000, but the fine was eventually reduced to $5,000. Considering that Kubly probably got much more than $5,000 in value for the services he rendered the bike-share company he once headed, he could chalk up the $5,000 as a cost of doing business. These two cases demonstrate the fact that, as you go up the ladder in government, the effectiveness of the Commission’s sanctions diminishes. A $5,000 fine on the guy at the top of the food chain has far less effect than the same fine applied to the guy on the bottom.

The next heaviest fine – which is not included in Barnett’s list but is described here – was imposed in 2016 on the head of Seattle’s Department of Transportation, Scott Kubly. Kubly failed to disclose to the City his prior relationship to a bike-share company when he was hired. This was material because Kubly was later influential in persuading the City to buy the company, a clear conflict of interest. (See more on that story here.) Kubly was initially fined $10,000, but the fine was eventually reduced to $5,000. Considering that Kubly probably got much more than $5,000 in value for the services he rendered the bike-share company he once headed, he could chalk up the $5,000 as a cost of doing business. These two cases demonstrate the fact that, as you go up the ladder in government, the effectiveness of the Commission’s sanctions diminishes. A $5,000 fine on the guy at the top of the food chain has far less effect than the same fine applied to the guy on the bottom.

But $5,000 is an unusually high penalty for the Commission in any case. Fines typically range from $250 – $2,500. For most City employees, the threat of a nominal cash penalty coupled with the embarrassment of having an ethics violation on record is enough to keep them honest. But when it comes to a powerful and determined politician like Lorena Gonzalez, this regime of token punishments and wrist slapping is not enough. On some level, the Commissioners know this, but they are powerless to do anything about it. At the first hearing, the Commission decided that Gonzalez had broken the rules, but they weren’t clear as to what cash penalty they could impose on her for doing so. The self-report form said there could be a fine of up to $5,000, but when Commissioner Norton asked Director Barnett whether the Commission had the power to impose a fine on a candidate over a voucher program violation, Barnett told her no. That left the Commission with only the one option of disqualifying Gonzalez from the program,. After deliberating on the matter privately, the commissioners decided this penalty was too harsh, especially since Gonzalez’ opponent, Pat Murakami, had already qualified for the program. And indeed, it would have been harsh to deprive Gonzalez of any voucher money. But it would not have been a fatal blow. Not by a long shot. Gonzalez was, after all, the incumbent. She had name recognition, the bully pulpit at City Hall, and access to Democratic Party and labor organizations that had already endorsed her and would surely have been willing to help her canvas. Moreover, by the time of the first complaint hearing, Gonzalez already had a war chest of $100,000 in cash contributions and was much less dependent on vouchers than her challenger Murakami, who had raised only about $60,000 at that time.

Pat Murakami is a neighborhood activist and small business owner running for Seattle City Council against incumbent Lorena Gonzalez. She has support from a number of grassroots organizations.

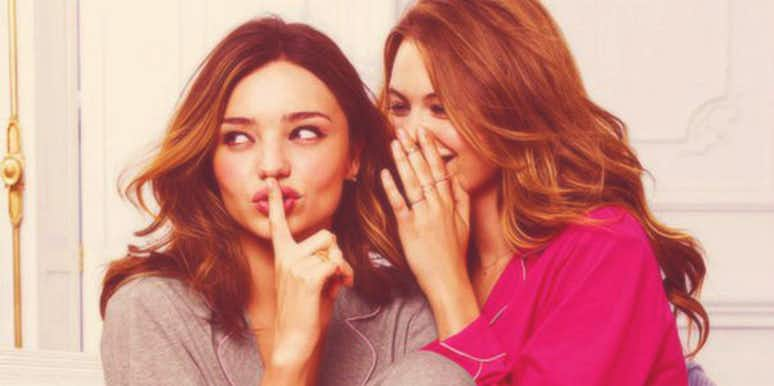

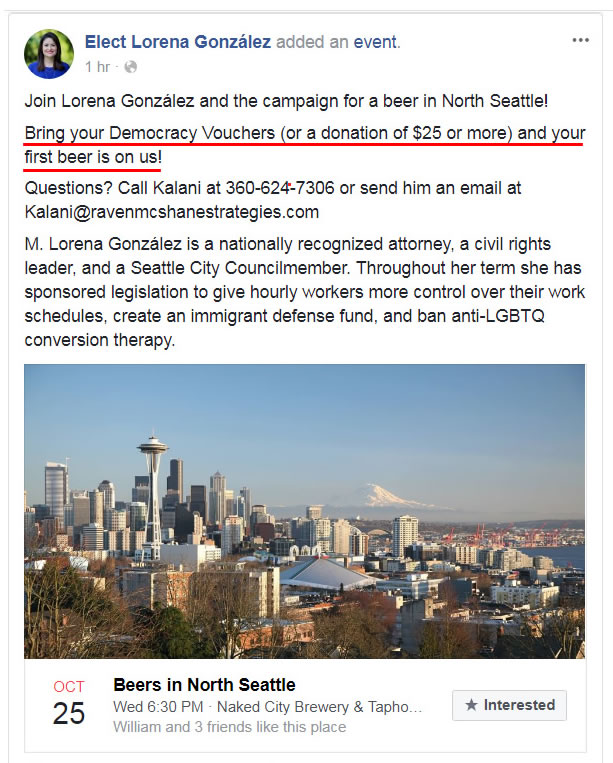

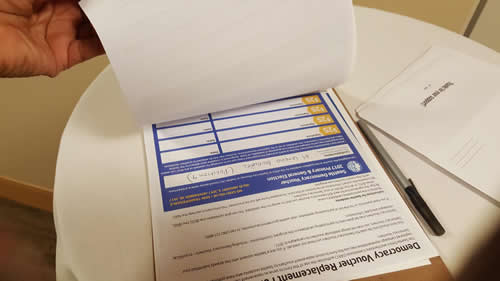

In the end, the Commission imposed no sanction on Gonzalez at all, other than to tell her she needed to do better and attend more forums in the future. While this might have seemed fair and reasonable to the commissioners at the time, it was exactly the wrong message to send to Gonzalez. As the Commission should have discerned from the evidence I included with the first complaint, Gonzalez was a bad actor, and she took the Commission’s failure to act as a green light to keep gaming the program. In the weeks following her absolution, Gonzalez continued to break voucher program rules. First she offered to trade “free beer” for vouchers at a party, and then she began leaving pre-completed democracy vouchers for voters to sign and send in to the SEEC at her events (see images below). Both are significant violations of program rules, and both have been the subject of additional complaints filed against her, though not by me.

“Free Beer” for democracy vouchers? That’s a no-no. Just days after the Ethics Commission exonerated Lorena Gonzalez for trying to game the voucher program rules, she was at it again.

At her campaign appearances Gonzalez left stacks of voucher applications with her name filled in the “Candidate Name” box. That is a violation of program rules. Only the person applying for the vouchers can fill out the form.

Think of what was at stake here. It was more than just a few thousand dollars in democracy voucher money. It was the integrity of the Democracy Voucher Program. And of the election itself.

Recommendations

- Recuse Recuse Recuse. Commissioners should recuse themselves whenever they are called upon to sit in judgment of any city official who nominated them or voted on their appointment. The Mayor nominates three Commission members and the Council nominates three; a seventh member is nominated by the other commissioners. All nominees are approved by the Council. This fact creates a sympathetic relationship between the Council and the Commission. And that’s a problem. For the same reason we would expect a judge to recuse herself from any trial where he was being asked to rule on a case involving a politician who had appointed him, we should expect the members of a quasi-judicial body like the Ethics Commission to recuse themselves from any case involving a mayor who had nominated them or a councilmember who had voted on their nomination. If a quorum is missing after such recusals, the gap can be filled by arbitrators or alternate Commissioners. The example of Lorena Gonzalez makes a particularly compelling case for recusals, since Gonzalez had either voted to approve, or served with, a number of the Commissioners. The impartiality of the body as a whole was thus compromised in this case.

. - Daylight the Commission. At the first Gonzalez complaint hearing, there was only one observer present. Unfortunately, that’s typical for Commission hearings. Usually there are no more than one or two people there to see what’s going on with our public officials, and these observers are typically involved in the case under discussion. The three people who were there for my appeal had been asked to attend by the Murakami campaign. There were some 15 observers total in attendance at the Gonzalez appeal hearing, but most of those were there for a high-profile complaint against another candidate for alleged campaign finance violations. On seeing these 15 people, Commissioner Norton remarked that it was the biggest crowd she could remember at a hearing. That’s telling.

.

The Seattle Times doesn’t cover Commission unless their hearing a case related to something splashy or lurid that’s already been in the news. For example, when former mayor Ed Murray asked the Commission if he could start a special campaign fund to help pay his legal costs in a child-rape case, and the Commission turned him down, the Times covered that story because it was part of the larger Murray debacle. They also mentioned the Scott Kubly penalty, briefly, because Kubly’s association with the bike-share company had already been covered by them and other media. But those are the exceptions.

.

Most Seattle-ites have never heard of the Ethics Commission, and among those who have, most don’t know, or don’t care, about its doings. And why should they, since the Commission doesn’t seem to do much anyway? Consider the example of socialist councilmember Kshama Sawant. Sawant uses taxpayer resources to organize support for her Socialist Alternative Party. She holds rallies and workshops inside City Hall that are led by Party members and other cronies and used primarily to drum up political support her and her policies. (See a recent example here.) Clearly this a violation of the Ethics Code’s prohibition on using public office for personal gain (4.16.020). To date, three complaints have been filed on Sawant in this regard (none by me), but none of them have been upheld. We, as citizens, need to care more about what the Commission is and educate ourselves about what it can do and what it can’t do.

. - Create a more ethical culture. The temple of democracy is only as sound as the pillars that support it. These pillars include the executive, the courts, the legislative bodies, and the media. As citizens, we tend to think of these pillars as impersonal bodies to which most of us have no personal connection and for which we bear no personal responsibility. But that is where we get it wrong. Seattle is in a state of moral decay now, and it is ultimately nobody’s fault but ours. For the past decade we sat on our hands as City Hall was handed over to a clique of social justice warriors who then handed our city over to developers and criminal vagrants. Even as our councilmembers make a great show of their commitment to “equity,” they are subverting the Constitution, by making laws out of our sight and without our participation. Next to what the City Council has been doing, Lorena Gonzalez’ cheating on the voucher program seems rather innocuous. But it’s all part of the same corrupt system, a system that will not be altered in its course by an Ethics Commission whose strongest sanction is a $5,000 fine, and that used but sparingly. As citizens, we are going to have to get more involved, and that’s as it should be. Of all the pillars of democracy, an engaged citizenry is, after all, the most important and ultimately the only one that matters.

–David Preston

*Although that is true in general, it is not true in the specific case of Lorena Gonzalez. As Commission Norton herself said at the initial hearing, of all the voucher program rules, the three-public-forums rule was the most straightforward and least complicated. Anyone with a sixth grade education could read and understand the definition of a “public forum.” And it’s printed right on the reporting form that candidates sign when they’re applying for the program.

Postscript: The dual role of the SEEC

For the record, I should say that there are some functions the Seattle Ethics and Elections Commission performs quite well. As a candidate and a campaign manager, I have had frequent interactions with both Director Barnett and Polly Grow, who heads the SEEC’s campaign finance section. Both Barnett and Grow have been among the most responsive and helpful government officials I have ever worked with. My criticism of the Commissioners and of the Commission in general should not be taken as criticism of them. –D.P.

Thank you for your article – very enlightening. You should submit this to the Seattle Times and other news outlets. Hopefully something will be done to make our Ethics Committee into a more independent body and make them more Ethical! It’s sad that no action was taken against Ms. Gonzalez in this election especially after the second and third violations (beer and pre-filled out vouchers at events).

Thanks for reading, ballardite! And keep doing so. There’ll be more good stories coming up.

Well said, David!