RCW 36.01.290 “Authorizing religious organizations to host temporary encampments for homeless persons on property owned or controlled by a religious organization”

RCW 36.01.290 “Authorizing religious organizations to host temporary encampments for homeless persons on property owned or controlled by a religious organization”

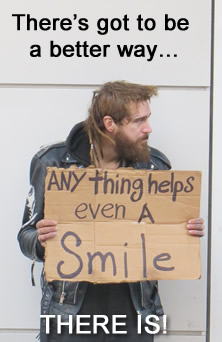

–This statute was enacted by the Washington State Legislature in 2010. It grants churches the right to set up temporary homeless camps on any property they own or lease, as an expression of the church members’ religious faith. The effect of this law is that church-sponsored camps must be permitted by local jurisdictions as long as they meet basic health and safety requirements. A non-religious organization would not be allowed to host such a camp, because the camp would typically violate a number of zoning laws and ordinances.

Nickelsville: Dream vs. Reality

In the fall of 2014, Pastor Steve Olsen of Seattle’s Lutheran Church of the Good Shepherd leased eight parcels of undeveloped land near downtown Seattle – probably for a trivial fee – from real estate developer Chris Koh. The lease was undertaken for the purpose of the church sponsoring a temporary homeless camp on the land under RCW 36.010.290. The camp was to be called Nickelsville and would be run by Olsen’s associate Scott Morrow and his non-profit Nickelsville organization. (Morrow also directs another, much larger, organization called SHARE, which receives over a million dollars in government grants and in-kind subsidies annually, in addition to tens of thousands of dollars’ in cash and in-kind donations from private donors.) Casework-type services were also to be provided another large non-profit that Morrow co-founded: the Low Income Housing Institute (LIHI).

During the year and a half Nickelsville was at this site, there were two rebellions against camp boss Morrow. The first one, in January 2015, was quashed after two weeks when Pastor Olsen, landowner Chris Koh, and LIHI CEO Sharon LEE threatened campers with a mass eviction. The second rebellion lasted from January 27, 2016, when a majority of campers voted to remove Morrow, to March 11, when Seattle Police moved in to dismantle the camp and evict the residents. The police were acting at the behest of Olsen, Koh, and Lee, who had sent a formal letter to the Mayor and City Council, asking them to evict the campers.

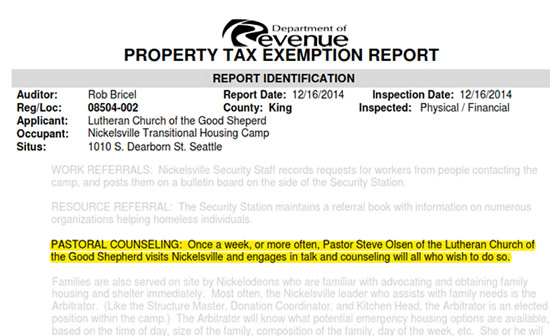

In December of 2014, Pastor Olsen asked the Washington State Department of Revenue (DOR) to give Mr. Koh a tax exemption for his property under RCW 84.36.043, which grants exemptions to landowners who use their land for “transitional and temporary housing.” The tax exemption was granted, and Koh saved more than $87,000 over two years on this property, even though about two thirds of the land sat empty during that time. (See that story here.) As part of the tax exemption application process, Pastor Olsen and the Nickelsville corporate entity (“Nickelsville”) were asked to describe for DOR the specific transitional housing services they’d be providing to the homeless people at Nickelsville. In the section that describes Pastor Olsen’s role, it says this:

PASTORAL COUNSELING: Once a week, or more often, Pastor Steve Olsen of the Lutheran Church of the Good Shepherd visits Nickelsville and engages in talk and counseling will all who wish to do so.

Although hosting a camp was ostensibly an expression of the Good Shepherd’s deeply held beliefs, this brief “pastoral counseling” item represents the only formal commitment the church and its pastor ever made to the people of Nickelsville. They were probably wise for not promising anything beyond that. The Nickelsville Dearborn camp was a good mile from the Good Shepherd Church, after all, and was cut off from approach on three sides. There is little to no parking in the area, and worse, it’s just across the street from another homeless area known as “The Jungle,” an infamous warren of smaller, illegal homeless camps plagued by trash, drug addiction, and outbreaks of violent crime. All of which meant that Nickelsville was not amenable to visits from Good Shepherd congregants – or anyone else.

So did Pastor Olsen do his weekly visits? Not according to residents I talked to. On April 17th, I visited with three former residents of Nickelsville – Jack, Daniel, and Troy – for about an hour. They had all been at Nickelsville during the time the Good Shepherd’s agreement with DOR was in force and Daniel and Troy had both been there for over a year. Troy had been the External Affairs Coordinator at Nickelsville. If anyone knew about the comings and goings in camp, it would be him. I read the “Pastoral Counseling Statement” from the DOR application and asked the men if they’d ever seen Pastor Olsen providing counseling to the Nickelsville camp. They chuckled and said: Never!

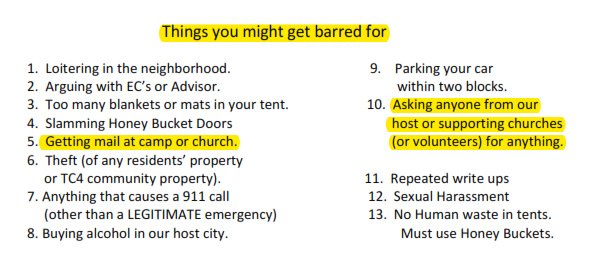

Troy: The only time we ever saw Pastor Olsen [pause] because it was forbidden by [camp boss] Scott [Morrow] and Peggy [Hotes] to talk to our religious sponsor. That would get you kicked out.

Daniel: He would drop off, like, canned food sometimes.Troy: Yeah, he would drop off water or canned food, and I will give him that much. But he did not stay more than five minutes, and the only person he would ever talk to was the person at the guard duty shack where he would drop stuff off.

Interviewer: But he did come once a week.

Troy: N-n-ot always. It was whenever, you know, maybe a week or two, here, there when he would stop by, but he never really did anything. And the only times we ever saw him was at the council meetings, the central committee meetings.

Interviewer: That was off-site, right?

Troy: Right. That was off-site. That wasn’t on the property.

Interviewer: So he didn’t come around to the tents and say, ‘Hi. I’m here, if you need to chat’? And nobody else came around to the tents and said, ‘Hey the Pastor’s here if you need some counseling or communion’?

Troy: No. There was one person who got removed from the camp permanently, a permanent bar, for contacting the pastor [without permission].

Other campers I talked to mentioned an agreement or contract between Pastor Olsen and camp boss Morrow. This agreement came into play most dramatically after the second rebellion against Morrow, in late January 2016. The camp was in upheaval at that time, and campers didn’t know whether they’d have a place to stay from one night to the next. Some of them appealed to Pastor Olsen to intervene with Morrow on their behalf, but Olsen, citing his contract with Morrow, told them he couldn’t get involved or even speak to them about it. A paid staffer at the camp told me he e-mailed Olsen asking for a meeting. Unfortunately, the pastor did not respond.

One camper told me that after campers had voted to remove Mr. Morrow from his position, the pastor told his congregation to stop visiting or supporting the camp in any way. However, some Good Shepherd church members ignored Olsen’s directive and continued dropping off supplies at camp. In speaking with people at the camp, they said they disagreed with their Pastor’s position on the matter.

Earlier this month, I sent Pastor Olsen two e-mails requesting a meeting to discuss his agreement with Mr. Morrow. Olsen did not respond, so there is no way to know what the nature of his agreement with Morrow was. However, documents and testimony from other camps also suggest the existence of such an agreement. Here’s an excerpt of a document that was given to me by a former camper at Tent City 4, a roving homeless camp that Morrow runs outside of Seattle. It shows that contacting churches directly will get you “barred” – that is, evicted, from camp:

An internal Nickelsville document from late December 2015 refers to a man (name redacted) who’d been evicted from the camp for contacting Pastor Olsen directly about something happening at camp. After signing an agreement to “follow established Nickelsville procedures” and not contact the church host himself, the man was allowed to stay at a different Morrow-controlled camp.

Given the mass of evidence, it seems likely that Pastor Olsen did have an agreement or contract of some kind with Morrow stipulating that the pastor could not speak to Nickelsville campers about any complaints they had against Mr. Morrow or the Nickelsville administration. Considering that such grievances would naturally have arisen from time to time, and that they could also be traumatic, campers would surely have wanted counseling and emotional support related to them. One wonders, then, how Pastor Olsen could reconcile his promise to Morrow not to talk to campers about issues they might have at camp with his commitment to DOR that he would “engage in talk and counseling with all who wish to do so.”

After the second Nickelsville rebellion in January 2016, trash pick-up at the camp was suddenly stopped. and sanitary conditions deteriorated quickly. I visited the camp in late February and found a small mountain of trash rotting just a few feet away from the food tent. Meanwhile food and water donations had slowed to a trickle as a result of a joint boycott by Olsen and Morrow’s Nickelsville organization. Pastor Olsen would likely have known about the trash. Or if not, then he should have known it. Yet even so, he made no effort to get the trash taken care of or otherwise intervene with Morrow in defense of campers’ basic human rights. The only subsequent record of his involvement with the camp is his name on the February 19 letter to the Mayor and City Counsel asking for the camp to be dismantled and the remaining campers – about 35 people – to be evicted. Ironically, Olsen’s appeal was based in part on his claim that “living conditions are quickly worsening.” and “trash is not being removed promptly.” –both of which problems he had a hand in creating.

Timeline

Before passing judgment on Pastor Olsen’s qualities as shepherd, let’s look at a general timeline of his involvement with Nickelsville. The timeline references events and facts that are covered in more detail elsewhere:

- Fall of 2014: Steve Olsen, on behalf of the Lutheran Church of the Good Shepherd, agrees to serve as the religious host of the Dearborn Street Nickelsville under RCW 36.01.290. At this time he may have made an agreement or formal contract with camp boss Scott Morrow not to speak with campers about events at camp or any complaints they had against management.

- December 2014: Olsen applies with the state Department of Revenue (DOR) for a “transitional housing” tax exemption for the five tax parcels on which Nickelsville was located as well as three nearby parcels. On December 16, a DOR agent visited the site with Olsen, Scott Morrow. In a written response to DOR’s questions, Olsen commits to visiting camp once a week or oftener, at which time he says will provide pastoral counseling to all who want it. (Several campers later reported that Olsen’s visits to the camp were sporadic and brief.)

- January 2015: A power struggle develops and camp boss Morrow is ousted. Olsen and others threaten the entire camp with eviction. In an e-mail to the rebellious campers, Olsen writes: “Scott’s role as staff person for the camp and liaison for the church host is an essential component of our working relationship. For this reason, your decision makes it impossible for us to continue as church host for Nickelsville.” Morrow is restored to power within days and the leaders of the rebellion are removed.

- June 2015: Following a lengthy review, DOR grants the Nickelsville property owner a transitional housing property tax exemption. In the application, Olsen says that all eight parcels will be used to support the camp; however, only the five smaller parcels (a total of one third of the land) were ever used. Total tax exemption: $87,000 over two years. Undeserved tax exemptions: $50,000. See that story here.

- October 2015 to January 2016: Another power struggle develops, culminating in late January with a second coup against boss Morrow. This time the rebellion appears to be successful and the campers dub their movement “Occupy Camp Dearborn.”

- Early February 2016: Olsen stops visiting the Nickelsville camp altogether and garbage service is discontinued. Olsen allegedly tells his congregation to stop supporting the campers, but some ignore him and continue delivering supplies. (Some campers said that when they asked Olsen to intervene on their behalf he told them it was forbidden by his contract with Morrow.)

- February 19: Olsen co-signs a letter delivered to the Mayor and City Council. In this letter, he describes the deteriorating safety and sanitary conditions and asks the City to remove the camp.

- March 11: Nickelsville is raided and closed by Seattle Police and the remaining campers are evicted.

- April 10: I try to contact Olsen seeking a meeting to discuss his “contract” with Mr. Morrow and other information about what happened at Nickelsville. He does not respond.

Freedom of Religion: Freedom to Abuse?

The experience of Pastor Olsen highlights the problematic nature of any law that, in the name of religious freedom, gives people a free pass to do as they please with vulnerable individuals who have been placed in their care. The intent of RCW 36.01.290 (allowing churches to host homeless camps) was laudable. However, in practice, it is easily abused, as we see with Nickelsville. Sadly, Mr. Morrow’s influence over the local clergy is not limited to Pastor Olsen: Morrow is connected to a number of host churches throughout King County, in fact. Not surprisingly, there have been rebellions, crime waves, and charges of abuse at many of them. Scandals are typically swept under the rug, often with the complicity of the host churches, who are loath to admit that their noble intentions could have led to such ignoble outcomes.

The RCW is obviously broken, but fortunately not so broken that it can’t be fixed. First, it must be amended to require that churches agree to be directly involved in managing any camps they host. Opening a parking lot, dropping off supplies, providing showers – these are all good, but they are not enough. If you’re going to transform people’s lives as an expression of your faith, then you have to talk with them, spend time with them, empathize with and mentor them. These are not tasks you can farm out to a third party . . . especially someone like Scott Morrow.

Second, the statute must ensure that homeless campers have the same basic rights as any other tenant. They must have the right to meet with their church hosts and the public, for example, either as individuals or as groups. And they must be protected from arbitrary eviction or punishment. If they are to be punished for some infraction of the rules, then they must have a right to a fair appeal, and such an appeal can only be ensured by the host or by the tenants themselves, never by a camp boss. Years of experience has proven that beyond all challenge.

Democracy Opportunity

If you are persuaded by this article, I urge you to get involved and contact the appropriate committees in the Washington State Legislature. Take a moment to share your thoughts with them, and ask them to revise RCW 36.01.290 so that churches hosting homeless camps are required to take direct responsibility for the vulnerable people under their care.

Send an e-mail to:

WA State House of Reps ~ Housing Committee (or visit their Web page)

WA State Senate ~ Housing Committee (Web page)

Story by David Preston. Photos by David Preston except as noted. The author wishes to thank the many brave and committed people who supplied information for this story.

Postscript

Pastor Olsen (Photo: Real Change News)

Pastor Steve Olsen and Church of the Good Shepherd currently sponsoring another homeless camp called Tiny House Village (see picture below). Tiny House Village is located on a church-owned property two lots down from the church itself. Although Tiny House Village is cleaner and better managed than Nickelsville, it too is run by Mr. Morrow, who exercises the same control there as he did at Nickelsville. Besides Tiny House Village, Morrow and his SHARE organization run two other “city-sanctioned” camps and shelters in Seattle, as well as two roving camps in King County. All of them receive some level of taxpayer funding.

Pastor Olsen and the Church of the Good Shepherd are under the jurisdiction of the Missouri Synod Lutheran Church, headquartered in Kirkwood, Missouri. You can find the Synod HQ on the Web here. You can e-mail a staff person here.

Church of the Good Shepherd’s info is here.

Pingback: Background on SHARE/Nickelsville lawbreaking activity – LPWA Policy Info