By David Preston

for Emmaline

Many of us in recovery say “I’m so glad I’m not trying to get sober now, I’d be dead if I was out there.” –Ann, a recovered addict and addiction treatment counselor.

.

Heroin saved my life. –Shilo Jama, Director, People’s Harm Reduction Alliance of Seattle.

.

If the War on Drugs really is a war, then drugs are clearly winning. The DEA might be out there interdicting drug shipments and arresting kingpins, but the sidewalks of my town (Seattle) are as soaked with narcotics as with winter rain. If I was a part of the drug culture, I could go downtown any time of the day and start buying and using openly. In full view of the police. With no risk of going to jail. Abstinence, education, and enforcement were the three pillars of American drug policy since the narcotics policy was first codified in 1914, but starting in the late 1980s, that approach began to lose ground in the face of the reality that many young people were going to try hard drugs regardless of what Nancy Reagan or their local D.A.R.E. program told them, and once they tried drugs, they’d get hooked. So what to do then? Send them to prison? That wasn’t working either, as evidenced by high rates of relapse among drug offenders returning to society. The fact that African Americans were being disproportionately imprisoned for drug crime made this solution all the more dubious. This is when “harm reduction” made the scene. Harm reduction advocates didn’t promise a Hollywood ending to the drug epidemic. They could demonstrate that it worked at least as well as everything else that had been tried to that point. And it was certainly cheaper. And more compassionate, too. We can engage constructively with people who are already hooked on drugs, was the idea, and we can use that connection to help them get off drugs and into a better life. A life of recovery.

Elaine Thompson / AP

At its core the theory of harm reduction holds that, in addressing the behaviors of individuals who are already harming themselves – by taking drugs, for example – we should take steps to reduce any incidental harm that is being done to them by others, including harm created by social stigmatization, imprisonment, and so on. A corollary to this is the theory that reducing harm incidental to the behavior is, in itself, a good outcome and can stand on its merits outside the question of whether the behavior itself is stopped. Therein lies the danger, but we’ll get to that.

What Harm Reduction Is Not

Harm reduction applies to high-risk and inherently damaging behaviors that are not part of a normal, healthy lifestyle. It does not apply to common activities of daily living, such as riding a bicycle. The graphic below, published by mainstream harm reduction organization in California, equates wearing a bicycle helmet while riding on a bike path to a drug addict using a clean syringe to inject heroin or a meth smoker testing his pills for contamination with fentanyl, which are things the group advocates for. While all those activities reduce harm in their own way, the flaws in the analogy are glaring. A more apt one would be that a clean needle is like a bicyclist wearing a helmet while riding on the freeway. At night. Helmet or no helmet, the odds are not in his favor.

According to the Santa Barbara Safety Coalition, a heroin addict using a clean needle is just like a bicyclist wearing a helmet. (Santa Barbara Opioid Safety Coalition)

A Survey of Harm Reduction Modalities

Free Drug Paraphernalia and Fentanyl Test Strips

In Seattle, local harm reduction practitioners like King County Public Health and the People’s Harm Reduction Alliance hand out clean syringes to anyone who asks, which can be picked at one of their pop-up tables or at any of several office locations. While this is sometimes called needle exchange, that term is misleading, since the client doesn’t have to hand over a dirty needle to get a clean one. Instead of needle exchanges, these locations should be called needle dispensaries. A single drug user may be given hundreds of needles at a time, and boxes of them are often given to known drug dealers, who then hand them out to their customers, streamlining the process for everyone.

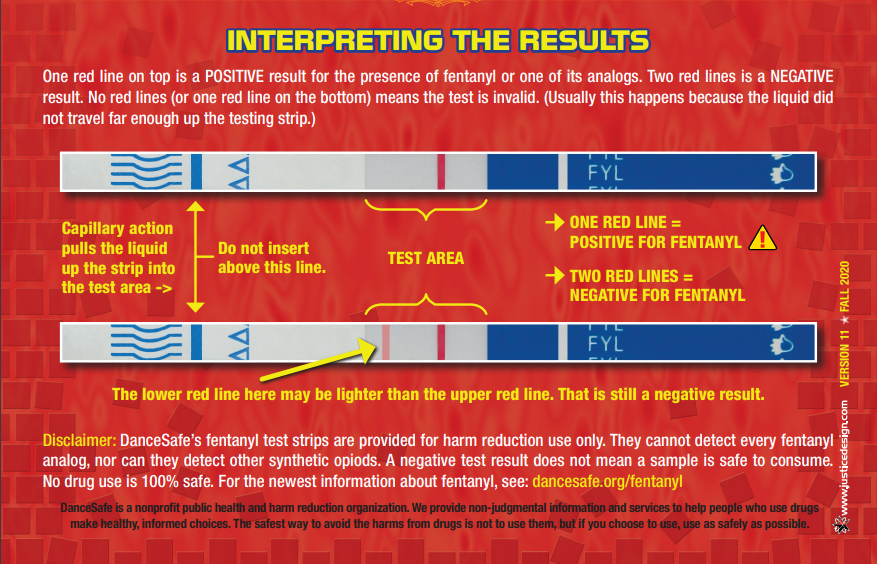

Along with needles, harm reduction practitioners in Seattle hand out other drug paraphernalia, including tourniquets (to raise veins for injection drug use); candles and glass pipes (“bubbles”) for smoking crack or meth; and foil, for smoking fentanyl. Drug testing kits are also available to help users determine whether their supply of heroin, meth, or cocaine has been cut with fentanyl.

How needle handouts and test strips can reduce harm. First used in 1988, the needle exchange is the oldest and arguably the most successful harm reduction program. The exchanges are intended to lower transmission of disease (like HIV and hepatitis) that spread through the sharing of dirty needles, and they have largely done that, as evidenced by the decreased incidence of these diseases among drug users. Theoretically, needle handouts connect drug users with information about treatment as well. At the place where the user picks up the needles, there might be pamphlets about drug-treatment options, or one of the staff might engage with them by saying: “Are you thinking about quitting? We can refer you to treatment.” It’s believed that users who come to same location repeatedly form trusting relationships with staff and are thus more likely to seek out help with the addiction. Test strips are another simple, proven technology, but they take some patience. And they don’t work for fentanyl users, obviously. Does handing out non-needle drug paraphernalia reduce harm? No, except in the sense that it can connect a drug user to resources, as described above. Sharing glass pipes or foil doesn’t spread deadly pathogens. Snorting straws and razor blades (for powered drugs) are among the paraphernalia that are handed out at harm reduction offices. Claims have been made that this technique prevents spread of bloodborne diseases like Hepatitis C, but those claims have not been well supported.

Medication-assisted Treatment (MAT)

Medication-assisted treatment, or MAT, has been around for decades and has evolved as new narcotics have entered the drug scene. Methadone is a well-known example of MAT for heroin use, and there are many newer MATs – like buprenorphine, suboxone, and ibogaine – that are available to drug users who want to ease out of withdrawal. MAT works by removing a user’s craving for the drug and/or blocking the physical symptoms of withdrawal. MAT is typically monitored by a physician or other medical professional.

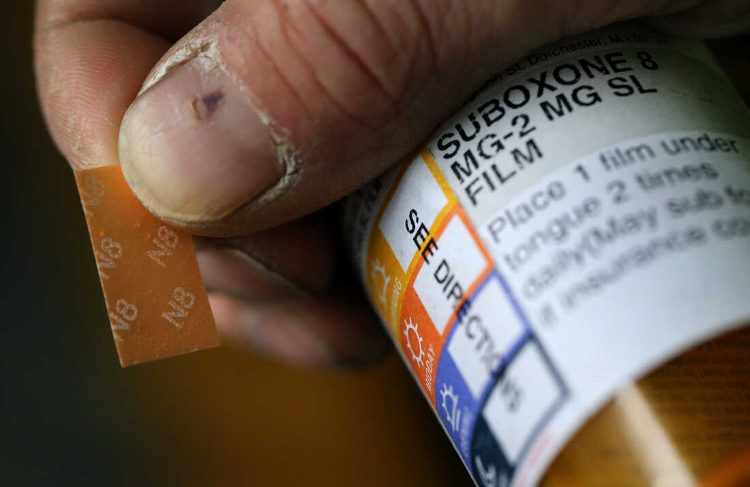

Suboxone is a cheap and easy-to-use addiction treatment medication. Image: NPR

How MAT can reduce harm. The object of MAT is to move the addict off the much more dangerous and addictive street drug onto a less dangerous, less addictive and drug that will, optimally, be gradually withdrawn or, failing that, used as a safer, long-term substitute for the addictive drug. MAT can be especially helpful in situations where sudden, forced withdrawal from a drug could be life-threatening, such as when an addict is admitted to a hospital or prison.

Low-barrier Housing

Low-barrier housing (also known as low-threshold housing) is subsidized short- or long-term housing provided to addicts with no expectation that they will quit using drugs and with no penalty imposed if they continue using. It’s understood, and can even be written into the lease, that residents will not be evicted for using drugs on or near the premises, though they can still be evicted for other things like damaging the unit or harassing other tenants. A history of drug use or drug possession charges is not a disqualifier for this type of housing. Low-barrier housing is at the core of the “housing first” model of addressing homelessness. The model emerged in the mid-2010s as an alternative to the dominant model of low-income housing at the time, which held that subsidized housing should be given only to those who were clean and sober or were actively trying to get there.

How low-barrier housing can reduce harm. According to the housing first model, the process of being evicted repeatedly and living on the street puts burdens on drug users above those they’re already trying to cope with. To survive on the street, an addict has to stay on the move and put a lot of work into “hustling” and this can interfere with his ability to make treatment appointments and stay in touch with counselors. The pain and stigma of living on the street can also cause an addict to retreat even further into the addiction. Lifting the burden of finding and keeping a market-rate apartment or shelter bed can help clear an addict’s path toward recovery.

Decriminalization & Legalization

Drug decriminalization is done on the state or city level and how it is implemented varies widely according to the local political culture. Narcotics aren’t legal anywhere in the U.S., but in 2020, Oregon voters formally decriminalized personal-use narcotics possession in a statewide referendum. In early 2021, the Washington Supreme Court struck down police stops for simple drug-possession as unconstitutional, throwing the matter back to the state legislature to rework the laws. Shortly thereafter, the legislature passed a replacement law (Engrossed Senate Bill 5476) reestablishing personal-use drug possession as a misdemeanor and directing that prosecutors divert an arrestee for evaluation and referral to “community based care” at least twice before booking. (Note: In King County a “personal use” amount of fentanyl pills is anything under 200 pills, which is a several days’ supply, according to my police sources.)

The practical effect of the law as updated has been the same as if the stricken section of the RCW had not been fixed at all but had simply been abandoned. Police and deputies around the state have not been stopping and arresting addicts on the street because they know they won’t be prosecuted and will probably not successfully complete addiction treatment once they are referred to “community care” either. In areas where drugs have either been formally or effectively decriminalized for some time, like Portland, Seattle, San Francisco, and several other larger cities, they are effectively legal as well, at least for personal use amounts. Decriminalization has been hailed as a step forward by harm reduction advocates, who liken it to Portugal’s efforts to to address drug use there, but what’s happening in the U.S. is quite different from the Portuguese approach. While Portugal has decriminalized drug use, it still imposes fines and other sanctions on drug users who are caught using or possessing drugs and refuse to get treatment.

How decriminalization can reduce harm. Harm reduction advocates believe that lifting the threat of jail encourages drug users to step out of the shadows. Keeping addicts out of jail also reduces the risk of a post-detox overdose. Opioid users who do a forced detox and withdrawal in jail often assume they can go back to using the same amount of drug they were using before the detox, but an opioid-free body is much more sensitive to the drug than an active user’s body, and a fresh-out-of-jail user can overdose on the same amount of drug he was injecting before detoxing.

Destigmatization

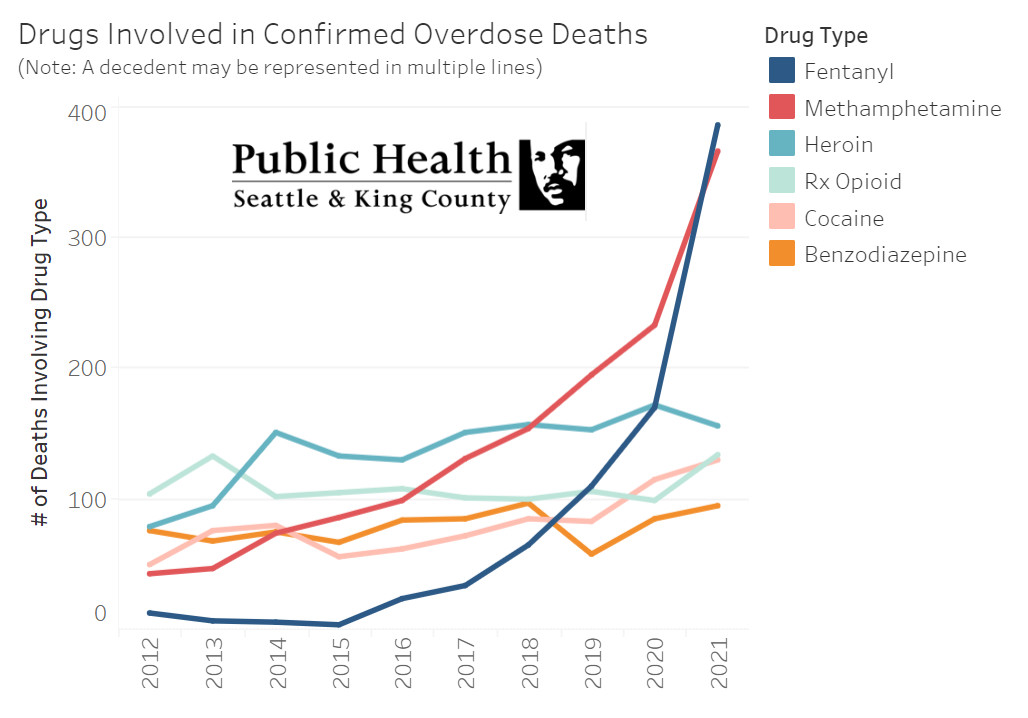

Drugs are Winning: A graph shows recent data for overdose deaths in King County. That heroin deaths are dipping slightly might be because heroin users are shifting to fentanyl. Click the image for more info.

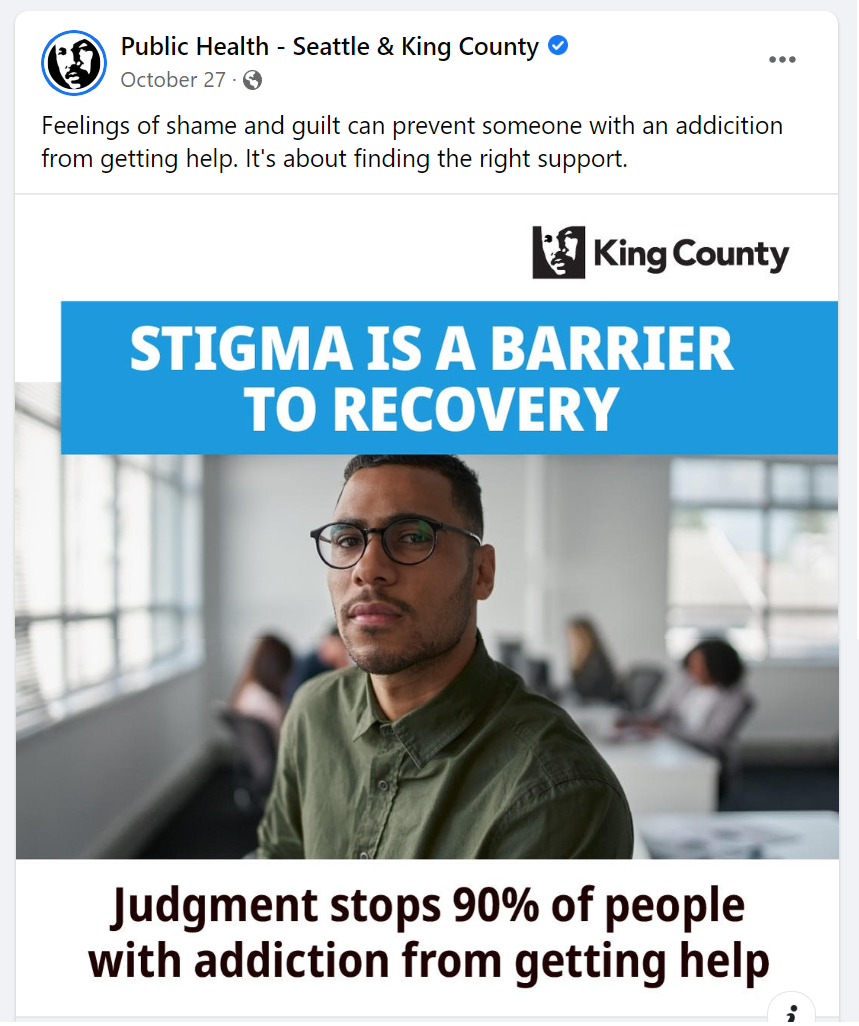

Stigma is the visible and felt disapproval society attaches to certain behaviors like prostitution, theft, and drug use; to social conditions, like poverty; and to physical conditions, like mental illness. With drug use, stigma can take many forms, from passersby avoiding the user on the street to employers refusing to hire anyone with a history of drug convictions. Destigmatization is the gradual process by which society becomes more tolerant of drug use and drug users. Drug use can be said to be completely destigmatized at the point where drug users feel no judgment from others and suffer no ill effects other than those caused by the drug. Collectively, harm reduction methods and the increasingly visible presence of drugs in the community contribute to destigmatization by making drug use seem more normal. Living near a needle dispensary, for example, or constantly watching drug use in the park, or seeing stories about Narcan on the news can have the effect of desensitizing people to the presence of drug use. Destigmatization is not a consciously implemented harm reduction method; rather, it happens incidentally to other methods, and it occurs so gradually that it is imperceptible to the public, and even to drug users.

Image (left): A 2022 Facebook post from the Seattle & King County Department of Health claims that 90% of drug users don’t get help due to stigma. The language isn’t clear, but what they appear to have meant “don’t get help” is “don’t seek help.” The underlying article cites a research paper that surveys studies from around the world where drug-users self-reported on perceived stigma and self-stigma (e.g., feelings that they are bad people and so don’t deserve help.)

How destigmatization can reduce harm. According to harm reduction theory, stigma and shame prevent drug users from getting help and can even increase their drug use as they turn to the drug for relief from the psychic pain of these negative feelings. With stigma gone and no fear of being shamed, drug users are more likely to step out of the shadows, admit to others that they have a problem, and seek help. At the same time, they will feel less compelled to use drugs “just to kill the pain” (of stigma).

Heroin Injection Sites & Narcan

Another form of harm reduction is the “safe injection site.” These sites go by several names, depending on who’s talking about them, but I call them heroin injection sites, since that’s the most accurate and value-neutral term. There are a handful of legal heroin injection sites around the country, and several years ago King County Public Health announced its decision to sponsor two of its own, but this plan never went forward, possibly because of negative publicity and a ballot initiative (which ultimately failed in court). Notwithstanding King County’s official lack of enthusiasm for the project, there are probably at least a few clandestine heroin injection sites in Seattle. As injection drug use is being eclipsed by fentanyl smoking and its associated rise in mortality, heroin injection sites seem to be losing their elan.

Formal heroin injection sites come with an agreement by local authorities not to arrest or interfere with drug users within a certain radius of a given site.

How heroin injection sites can reduce harm. The most immediate risk of harm presented by heroin is overdose. A heroin injection site is a clinically supervised room where drug users can go to get a clean needle and inject heroin under the eye of someone who is trained to revive them with the opioid neutralizing drug Narcan should they overdose. While overdoses still happen frequently at these sites, the sites’ promoters can truthfully say that few or no overdose deaths have occurred there. Lethal overdose is a common occurrence among heroin users, and if we assume that any one use of heroin could lead to an overdose, it’s correct to say that injection sites save lives, at least in the short term. As with the needle dispensaries, there is the “engagement” factor as well. Staff at heroin injection sites can offer treatment referrals and other potentially life-saving services to any drug user who comes in. In Seattle and other cities, Narcan is also given to first responders and non-clinical civilians along with training in how to use it. Narcan’s low cost, ease of use, and efficacy as a life-saving treatment for opioid overdose has been demonstrated.

Downsides

Each of the harm reduction methods I’ve described has its specific shortcomings. Needle exchanges – more properly called needle dispensaries – have been criticized for contributing to needle trash on the streets, for example, while heroin injection sites tend to increase drug use in the areas where they’re located, because addicts (and the drug dealers who service them) gravitate to those spots. And since the addicts who use injection sites don’t use them 100% of the time they will still be injecting themselves out on the streets around the clinic at least some of the time. And dying, too. Treatment medications (MATs) like methadone can create lifelong dependencies for recovering drug addicts and can be abused by active addicts who sell them them on the street or use them to create a “designer high.” Even life-saving Narcan can theoretically be abused, though evidence that it’s actually happening is scant. In practice, the housing first model is such an obvious failure that it’s been discredited even among many of those who once championed it. The basic flaw in the model lies in its failure to grasp the realities of addiction. The program was designed to accommodate maintenance addicts (i.e., addicts who don’t increase their dosage over time or experiment with new drugs) and those without significant behavioral issues. It works well for addicts who can use drugs while otherwise keeping their lives in order. But this type of addict is in the minority among narcotics users. Much commoner is the user who will continue their life on the street, regardless of whether they’ve got a room to flop in at night. In the photo below, the woman in the turquois jacket below sitting outside a rent-subsidized “housing first” high-rise in downtown Seattle. “She wanders around the area using and dealing drugs all day,” the photographer told me. “When I saw her, she had a wad of cash in her hand and a little drug briefcase. She lives in a tiny house village.”

Note: “Tiny house village” refers to any of a dozen or so city-sanctioned low-barrier shantytowns located around Seattle and run by one of the state’s largest low-income housing providers: LIHI. In addition to its taxpayer-funded apartment complexes, LIHI gets around a million dollars per village per year to provide substandard housing for chronically homeless drug users and prostitutes. The organization says it provides on-site caseworker services, but it does not share information on the rate of long-term recovery of residents, and there are many reports of drug-related violence inside the shantytowns.

I spoke about this phenomenon of drug users who have housing staying on the street with Andrea Suarez, director of a street outreach and clean-up program called We Heart Seattle: “It’s a daily occurrence for me to see people loitering on the street using or in doorways, slumped over,” she told me…

The dead giveaway is that there’s a key around their neck or a key card. In casual interviews, people tell me that they like to hang out with their communities in what we call an ‘open air drug-scene’ where they can buy, sell, and use dope. Tents are often set up just for the purpose of using drugs in green spaces and in parks. I wish I had a dollar for every time somebody said, ‘Oh I’m fine. I have housing; I just hang out here. And now that prostitution is the number one funding source both men and women use to support their fentanyl habit, tents are set up to turn tricks for fast easy cash. There are predators who drive up and down Third Avenue waving cash out their window and using nonverbal gestures to solicit for a sexual favors in exchange for cash.

One thing addiction counselors always tell their clients is to avoid returning to the social milieu where they drank or drugged, but this isn’t possible for people living in low-barrier housing. Since the housing is set aside just for drug users, all the residents in those buildings use drugs, and drug dealers congregate nearby to service them. In the event that an addict living in low-barrier housing gets clean, it will be nearly impossible for them to stay that way, because temptation is everywhere. They can always move out, but the costs of getting into a market-rate apartment might be prohibitive. They can put themselves on a wait list for a subsidized non-low-barrier unit, but it might be years before their name comes to the top. Faced with these choices, many low-barrier housing residents simply give up on recovery. Low-barrier housing disincentivizes drug users from quitting and traps them in their addiction.

Decriminalization of narcotics has happened in a piecemeal way around the country, which has led to drug tourism, where drug users migrate from more restrictive states to less restrictive ones to get drugs cheaper and with less legal risk. Cannabis, which is now fully legal in 21 states, is a good example of how this works. States where recreational marijuana is fully legal, such as Washington and Colorado, have documented the phenomenon of cannabis tourism, which they see as a boon, since the trade is taxed and generates additional economic activity. Narcotics tourism is happening in these two states in much same way, except that narcotics tourism is an economic drain, since the tourists tend to stay on and live on the streets, creating a burden in the form of added medical expenses, crime and court costs, and decreased quality of life for the hosts. Drug destigmatization can lead to drug normalization, which causes harm to society by lowering the quality of life in areas where drug use is prevalent. It causes harm to drug users by leading them to believe that drug use is a sustainable, low-risk activity and a valid lifestyle choice.

Image (left): The photo on the left shows a woman injecting heroin into the neck of a man in a touristy Westlake Park area of downtown Seattle. Scenes like this are common there now, often taking place within view of police. Seattle has moved past destigmatization and decriminalization of drugs to full-on normalization, with predictable results. Once any behavior is normalized, more people are likely to try it and the people already doing it are less likely to stop. (Why should they?)

True Costs

The cost of harm reduction programs can’t be measured simply in terms of dollars expended on those programs, but if they could be, the cost side of the equation would be trivial. If you totaled the amount spent by governments and NGOs to distribute free needles, run methadone programs, and so on, it would be just a sliver of total healthcare spending pie, and harm reduction advocates can argue, correctly, that that amount would dwarfed by the money municipalities save, at least in the short-term, in the form of decreased overdose hospitalizations and savings in court costs and jail expenses associated with decriminalization. By that calculus alone, harm reduction is an easy win, and that’s without counting the value of lives saved by the strategy. The problem with this view is that it takes no account of the social costs of allowing drug users to continue their addiction unimpeded: Needles on playgrounds are one such, cost. Having vagrant drug users shooting up on the street and living in parks is another. Increased property crime due to drug users stealing to support their habit is still another. These things are often dismissed by harm reduction advocates as “quality of life issues” or “nuisance crimes” and people who complain are accused of betraying their “privilege.” This gaslighting drives a wedge between addicts and the non-addicted majority, which is ultimately counterproductive to harm reduction’s objectives. Can we blame parents for putting their children’s safety above a drug user’s well-being, especially when the drug user doesn’t seem to particularly care what happens to him? People negatively impacted by harm reduction is a growing demographic, and it’s one that matters, politically. Drug-related squalor is growing worse in big cities, like San Francisco, that have robust harm-reduction programs, and that in turn is creating mass movements to reject “progressivism” in those cities.

But what about injection sites? Don’t they save lives? There are no sanctioned heroin injection sites in my city of Seattle, but there are five around British Columbia, just a few hours away. Given the cultural similarities between Seattle and BC, whatever works there should also work here. But do Vancouver’s injection sites work? Harm reduction proponents say yes, but they don’t explore what success means, other than to say that no one dies at an injection site. And that’s true, as far as it goes. Which is not very. An injection site will prevent a drug user from overdosing to death only while he’s at the facility. But to be protected from ever dying of overdose, he’d have to visit the site each time he injects (typically twice a day) for the duration of his addiction, even if it means he has to travel across town by bus every day. For years. Is that a realistic expectation?

A heroin user slumps against a wall in downtown Seattle. Would he be able to make it across town to an injection site twice a day?

Baked into the injection site philosophy is the assumption that drug users have a strong will to live and are willing to follow a demanding regimen in order to protect their health and stay alive. But is that assumption true? It might be true for the addicts who conscientiously use the sites, but in the main, it doesn’t seem to be. If most drug users cared that much about their well being, doesn’t it stand to reason that there would be far fewer addicts?

Where’s the data?

Even if injection sites got just a few people into long-term recovery, a case could be made that the sites are worth all the controversy and expense. Unfortunately, I couldn’t find any studies to support the claim that injection sites save even a few lives over time. So why are there no studies? The difficulty of recruiting participants could be one reason. There are many factors at play in a heroin user’s addiction: he might quit and relapse repeatedly, for example, going in and out of treatment programs. He might spend time in jail. Addicts tend to have unstable living situations, even the ones who live indoors. A given addiction might move from apartment to apartment and from city to city several times in the course of a few years. There might be long periods where he’s incapacitated or otherwise out of touch. How does a clinical researcher monitor an individual like this closely when even family members can’t manage to?

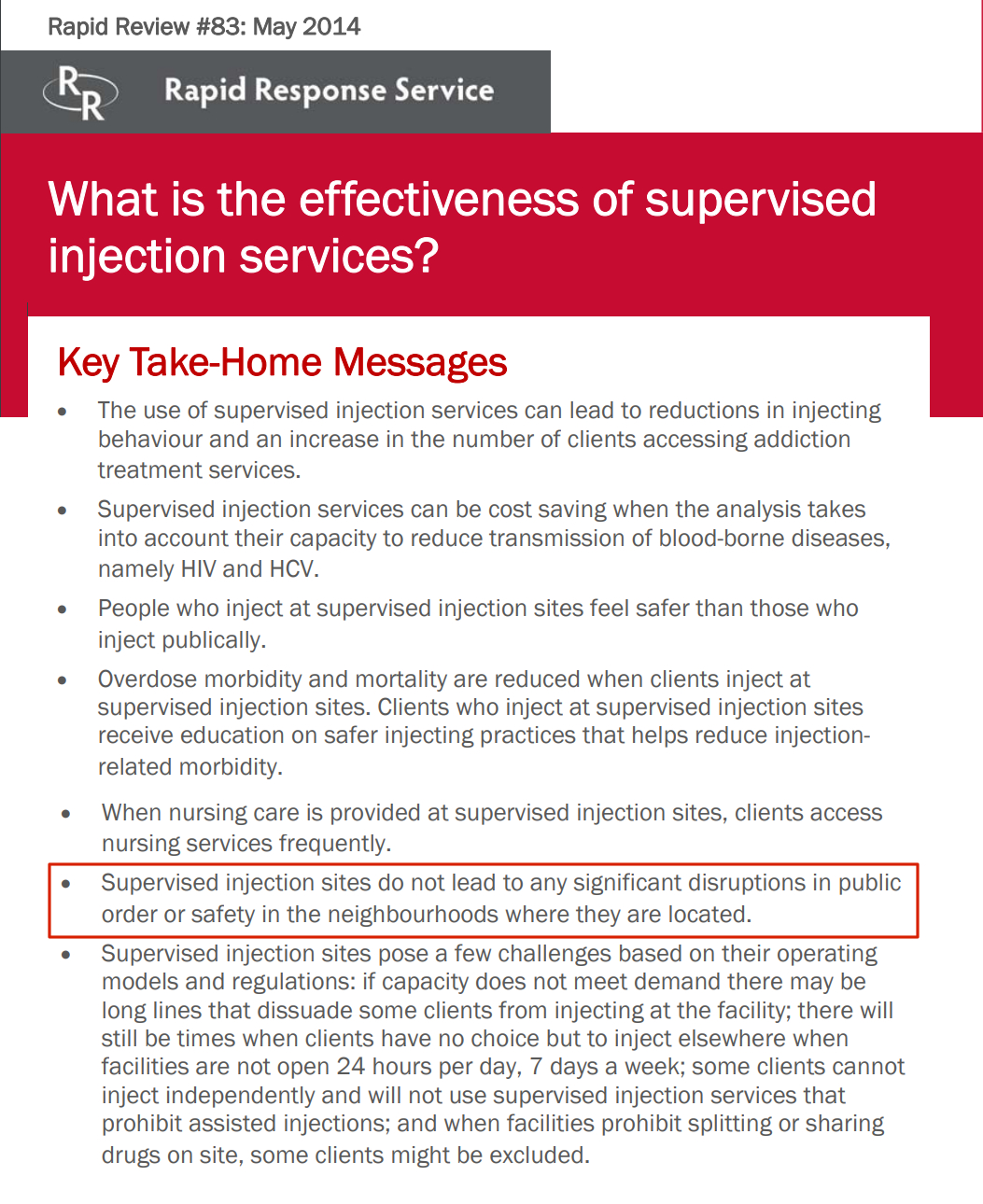

Still, it’s possible to produce a meaningful study on such a population, as long as the initial sample group is large enough to allow for attrition. Let’s say you start a four-year study with a sample group of 1,000 participants* and you lose touch with 75% of them during that time. That leaves 250 participants who used the injection site more or less consistently, or otherwise stayed in touch, and they either stayed on heroin or got off it during the study period. Or they died. For more on how a study could be set up, see Appendix D. When the initial study period ended, participants’ progress would be followed over time to determine whether their use of the injection site correlates to their long-term outcome. If the sites saved just a few dozen people over the course of the study by encouraging them to get treatment and recover, the public could be convinced that the sites were worth the social costs. So why aren’t injection sites gathering that kind of data? Are they too busy saving lives to even keep track of how many they’re saving? Or is there another reason? Studies on users of injection sites typically track the number of referrals to treatment or short-term injection behavior. They don’t track year-over-year or long-term survival rates of participants. This 2014 summary of a review of 20 studies is typical in its assessment of study results. Note that the words survival, recover, and recovery are absent from this 7-page document. Also note the claim that injections don’t “lead to any disruptions in public order or safety in the neighborhoods where they are located.” This claim, which is probably self-reported by clinic staff or sympathetic public offices, contradicts the testimony of hundreds of actual neighbors living in those areas. It calls the reliability of the study as a whole into question:

Insite: A Case in Point

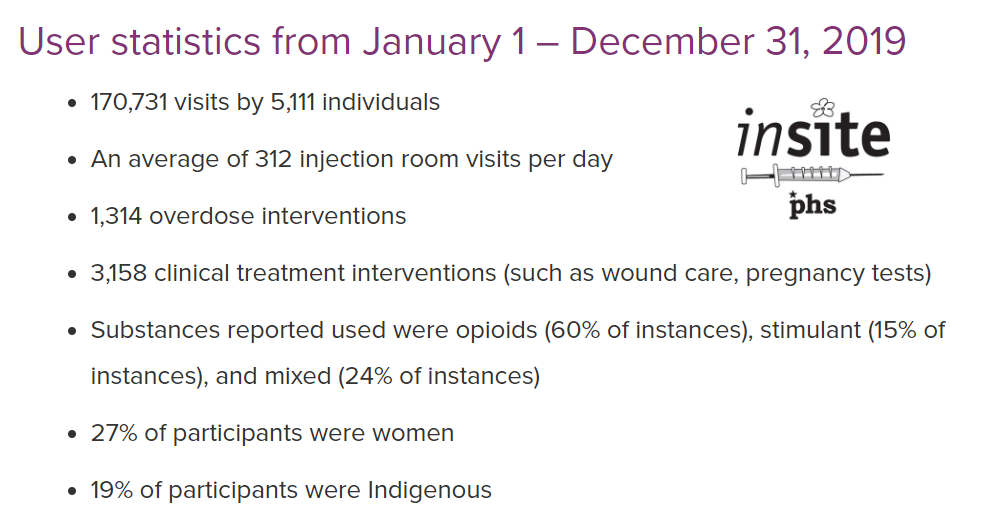

Vancouver Canada’s Insite injection clinic has been running since 2003. Its operator, Vancouver Coastal Health, estimates that in 2019 there were 170,731 visits by 5,111 individuals. With user numbers like these, and nearly two decades of experience, there should be an ample number of study participants and outcomes to demonstrate that Insite is saving lives in the long term by facilitating treatment or that it’s at least beating the performance of doing nothing. And yet there don’t seem to be any studies on that. I contacted Vancouver Coastal Health and asked a nurse in the public relations department named Deanna Lancaster if VCH had any data correlating long-term recovery to the Insite clinic. After asking me what I wanted the data for, she ghosted me, so I conclude that VCH doesn’t have that data. If they did have it, one would think they’d be shouting it to the skies

Image (right): The Insite heroin injection site in Vancouver, Canada proudly cites the number of clients served and the number of overdose “interventions.” What they don’t mention is the number of treatment referrals and the number of clients who have quit using heroin altogether. Source: Vancouver Coastal Health

According to Insite’s guided tour video below, you don’t need to provide any personal information to the staff. You have to be at least 16 years old (though they can’t make you prove this), and you have to give them a name. “But it can be whatever name you like,” the narrator says. “Make one up if you like.” If you’re using a made-up name, they ask only that you use the same name every time, presumably so Insite can track the number of unique clients served. But in this system, a client could use the clinic one day and die on the street of an overdose the next day, and no one would be any the wiser. Insite would count the client visit the day before and call it a win. Does this sound like real epidemiology?

“It looks more like a hair salon than anything else.”

Inside Insite Video: This thinly disguised promotional film on Vancouver’s Insite clinic devotes 10 seconds of an 8-minute presentation to treatment, and none to Insite users’ long-term recovery rate. The narrator reveals that users must ask about treatment, since that information is not volunteered. “Maybe you want to ask staff about treatment options,” she says, “like a third of the other people who visit here. And if you’re ready [!] and there’s room [!] someone’ll take you upstairs to Onsite, a detox and housing program on the second floor.” One wonders what a drug addict has to do to show Insite staff that they’re “ready” for treatment beyond simply asking for it. Also, what’s meant by “if there’s room”? Does Insite have to have a bed ready in their own building before they’ll refer a drug user for treatment?

The Elephant in the Room: Enabling

Why is it necessary to collect data on addiction treatment and long-term recovery in relation to harm reduction? Why isn’t it enough to show that injection sites reduce harm in the moment? To understand this, you have to know something about the psychology of addiction. Recovered addicts that an addict won’t quit the habit until the personal costs of the addiction outweigh the benefit in the addict’s already drug-clouded judgment. (This is known in 12-step parlance as “hitting rock bottom.”) Anything that makes an addiction easier for the addict to support – like free needles, for example, or a cozy place to shoot up – will forestall the day of reckoning when the addict has finally had enough and decides to quit. This in turn makes it likelier that the addict will eventually die of an overdose anyway. And in the meantime, while the addict is still using, he will continue engaging in all the other unsafe (that is to say harmful) behaviors typically associated with drug use. Behaviors like stealing and prostituting to pay for the drugs. And hanging out on the streets between fixes as addicts are doing in the streets around Insite.

Do staff at Insite encourage their heroin-using clients to get treatment? It doesn’t look like it. The vibe is gloomily sterile as you can see from the picture above. There’s no vase with flowers at the desk, no low-key art prints on the walls. Needless to say there are no posters advertising treatment services or mentioning the long-term risks of “safe” drug use. You check in with a name, get a needle or whatever, sit down at a booth, and inject. Afterwards, you chill out in a waiting room. And then you leave.

Free Supplies: Another way of enabling

In July of 2020, the People’s Harm Reduction Alliance in Seattle advertised a service in which they would mail a variety of free drug supplies to anyone who filled out an online form. The Safe Seattle Facebook page had a volunteer request a variety of supplies and they were duly received. At no point, the volunteer reported, did anyone at PHRA offer him treatment options. That story is here. Three years before that, I visited the PHRA office in the university district and got a guided tour from the then director, Lisa Al-Hakim. Although there were stacks of literature on various other health services, the only information about treatment was a “call this number for help” item I found in a single dog-eared pamphlet that was lying on a coffee table.

What former heroin addicts say about harm reduction

I manage a Facebook page that deals with public safety, and there are many recovered drug addicts who follow that page. They often tell me that they’re glad they kicked their drug habit before the age of harm reduction, because if they’d been addicted during the harm reduction era, they might never have gotten clean. Here are some typical comments:

I was a heroin addict in the late 1980s, back when possession of narcotics was a felony and you could get arrested and do time for simple possession. That is how I eventually got clean, by getting arrested and going to jail. The first time I was arrested I was in jail for 30 days, where I suffered withdrawal from heroin, cold turkey, and I was released after 30 days on the condition that I go straight into a 28-day rehab program, which my parents paid for. I was introduced to NA and AA thru the rehab, and was able to stay clean for about 2 years. Then I got back into the drugs, got strung out, and was arrested again for possession of heroin. I was given a 6-month sentence, which I did in work release. Once again, I kicked the drugs cold turkey in jail, was sent from work release to the King County Jail, then sent to the North Rehabilitation Facility in Shoreline [now closed –Editor] and finally returned to work release, where I finished my sentence. My caseworker there let me go to NA and AA meetings every day, and I have remained clean off drugs ever since, going on 25 years now. Now then, if I was a drug addict today, I would never have gotten clean. I would never have been arrested for possession, and I probably would have eventually died or ruined my body like a lot of my associates did. I consider myself lucky to have gone to jail long enough to get and stay clean. The decriminalization of hard drugs was a huge mistake – the only people who support it are either drug addicts or people who have no clue about the nature of addiction. –Paul

.

I know from frontline experience that housing first is not a solution for people who need treatment for a disease. I chose to move into a recovery house where I became manager and the zero tolerance for drug use helped separate me from people who used. The requirement to go to anonymous [12-step] groups helped me build a life where I could identify with others. Subsidized housing first that puts people who are at risk in apartments with other who are at risk creates a slum. There is no enforcement to better oneself. It looks nice when the governor comes to town, but day to day these places are trap houses and the people who live there are trapped and they cannot move without risking losing their housing. So even if they want to do better or be better they cannot. –Ann

.

I genuinely believe with every fiber of my being I’d be dead if harm reduction and safe supply was a thing when I was a practicing addict almost 20 years ago.–Vanessa

.

I’d be dead if this crap was around when I was a heroin addict. BTW: I am in favor of actual needle EXCHANGES, not needle dispensaries. –Jim

Why don’t harm reduction advocates push recovery?

There are two main reasons, the first being that the people running those locations believe that emphasizing recovery is a form of stigma and will discourage drug users from going to free needle tables and injection sites. There are no controlled studies to test this hypothesis. Second, many modern harm reduction advocates feel that using drugs is a valid lifestyle choice and not something that needs to be treated or recovered from. There’s nothing bad about drug use that can’t be addressed with harm reduction, they reason.

Shilo Jama, longtime director of Seattle’s People’s Harm Reduction Alliance (PHRA) has championed the drug-use-as-lifestyle idea and feels drugs shouldn’t be sanctioned in any way. He is himself a heroin user, and the message he gives other addicts is one of unconditional love and acceptance – acceptance of them and their drug-using behavior. Jama, who has no professional clinical qualifications, was an expert panelist on King County’s Opioid Addiction Task Force and was involved in developing the County’s plan to create several injection sites around the county. In a 2015 interview with KUOW, he explained that heroin was a positive force in his life. [Click on the picture below to hear that interview.]

Image: In recounting how he became the director Seattle’s premier harm-reduction organization, Shilo Jama talked to KUOW about how losing a friend to heroin inspired him to get involved: “I wasn’t going to let another person die from a needless death,” said Murphy, now the head of the alliance. But he didn’t want to give up drugs. Drugs had opened his mind, and they were a part of his social life. “To be perfectly honest, I have always enjoyed drugs and they’ve always made my life better,” he said. “I saw drugs as not only a means to escape but a means to inspire me for greatness.” Article here Now a harm reduction crusader, Jama has threatened to open his own unsanctioned heroin injection sites if King County doesn’t move forward with their own commitment to do them. Images: PHRA and KUOW.

Image: In recounting how he became the director Seattle’s premier harm-reduction organization, Shilo Jama talked to KUOW about how losing a friend to heroin inspired him to get involved: “I wasn’t going to let another person die from a needless death,” said Murphy, now the head of the alliance. But he didn’t want to give up drugs. Drugs had opened his mind, and they were a part of his social life. “To be perfectly honest, I have always enjoyed drugs and they’ve always made my life better,” he said. “I saw drugs as not only a means to escape but a means to inspire me for greatness.” Article here Now a harm reduction crusader, Jama has threatened to open his own unsanctioned heroin injection sites if King County doesn’t move forward with their own commitment to do them. Images: PHRA and KUOW.

The Shilo Jamas of America – and there are many – don’t especially want drug users to give up their habit. What they want is for everyone else to get over their hang-ups about drugs.

11 Things We Can Do To Make Harm Reduction Work Again

- Return to an evidence-based approach. Some harm reduction methods, like needle exchanges and MAT, have been proven to reduce harm with relatively low collateral costs. Others, like “housing first,” have not. Rigorous independent study needs to be done on the relationship between each harm reduction method and long-term recovery and survival rates. Any method that can’t demonstrate a positive relationship to recovery should be reworked or discontinued. At the top of the list for scrutiny should be injection sites.

. - Make recovery and long-term survival a major goal. The dominant trend among today’s harm reduction advocates is to see recovery as optional. That’s wrong. Instead, it should be one of the two pillars of the program. Treatment options should be prominently featured at any harm reduction location and providers should assertively offer these options to drug users in an appropriate, non-judgmental way. There are many successful models of recovery out there and many established recovery providers and harm reduction providers should be partnering with them.

. - Spend more on treatment. Injection sites have been embraced by the public because they seem so much more available than treatment and recovery. Outreach workers have horror stories about people on the street saying they want to get treatment right now who get turned away because there are no available treatment beds nearby. While it’s not realistic to expect that there will always be an open treatment bed in the neighborhood, we could be doing more to increase the supply. Injection site advocates claim they’re saving millions of dollars by reducing the money spent on emergency room treatment of overdose cases, and if that’s true, shouldn’t we be spending some of the savings on treatment beds?

. - Earned housing, not “housing first.” Having a clean, safe place to stay does aid in the process of recovery; therefore, safe shelter and treatment beds should be a top spending priority for government. However, moving an active drug user into an apartment with no accountability has not been shown to improve recovery rates. Often, the addict ends up back on the street and the unit is trashed, which drains resources from an already overtaxed system. Instead of getting handed the keys to an apartment, an addict should be placed into detox and treatment. Then they can be given a pathway back to permanent housing. Once they’ve achieved certain milestones (getting clean, meeting with their counselors on time, staying out of legal trouble, etc.) and are able to abide by the terms of a lease they can be prioritized for a subsidized apartment. People who want to hang out on the street or in a tent in the park should not be qualified for a housing program.

. - Call things by their right names. If you asked most people on the street what drug addiction is, they’d be able to give you a working definition. However, if you asked them about “substance abuse disorder” you might get a blank stare. When we change the names of things to avoid hurting feelings, we lose something in the process. Shacks for drug users don’t constitute a “tiny home village” and there’s nothing “safe” about injecting yourself with heroin. Even calling drug addiction a disease is problematic. While it is partly a disease, it is partly a choice as well, and if we’re not going to be honest with ourselves about that, we’re not going to be able to address it. When you have media using the term “safe injection site” with a straight face and public health officials referring to heroin as “treatment” you’ve gone too far.

. - Keep the neighborhood clean. When needle exchanges were replaced with needle dispensaries, the neighborhoods around them started getting trashed up with needles. Thus, in reducing harm for one population (drug users), the handouts increased harm to another (the neighbors). Needle dispensaries should be phased out and true needle exchanges brought back. And while the transition is happening, any group operating a needle dispensary should take responsibility for reducing harm to neighborhoods by organizing needle clean-ups. If a group has the resources to give clean needles away, they’ve got the resources to pick up the dirty ones.

. - Come to grips with drug tourism. Cities that normalize drug use become meccas for drug users from around the country, and these users become a significant burden on emergency response systems. “Treatment on demand” is a nice slogan, but it’s unrealistic to expect that treatment beds can be expanded to accommodate every addict who turns up from someplace else wanting to be helped. Cities should do unbiased** surveys on the user population so they can understand how normalization is contributing to their burden and take steps to alleviate it. Such steps could include bus tickets home for drug tourists and a redistribution of federal spending to support the cities that are struggling to support an influx of addicts from other states.

. - De-platform the crusaders. Seattle’s Shilo Jama, an active heroin user, represents a major tendency among today’s harm reduction activists. He believes that using drugs is always OK and can be a positive thing. Accordingly, he never suggests to anyone who comes to his needle dispensary that they should get into treatment. That’s not harm reduction, it’s harm creation. No one with this outlook should be receiving taxpayer money or running any government-sanctioned program. Or serving on panels of experts.

. - Implement balanced public oversight. Every town and city that has an organized, government-sanctioned harm reduction program should also have an oversight board that monitors the program’s activities, measures its effectiveness against its stated objectives, shares its findings with the public, and makes recommendations. The board should comprise a balance of providers, addiction experts, law enforcement personnel, active and recovered addicts, family members of addicts, and representatives of the neighborhoods affected. Such oversight boards are necessary to counteract the tendency of harm reduction activists and their allies in government to go rogue with their programs.

. - Rely on the justice system as needed. The assumption that most drug users want take care of themselves and know how to do that is wrong. Differing levels of agency and physical condition among addicts require different responses. Drug users who are mentally or physically incapacitated should be offered harm reduction while being strongly encouraged to get into treatment. Those who refuse treatment but continue engaging in problem behaviors in the community should be subject to the law. Since, 1994 King County has had a “drug court,” and it’s still nominally in operation, but in recent years it’s been fallen out of favor and use. It’s time to bring Drug Court back. Observational holds and/or short-term involuntary commitments, assisted with MAT, should be applied to addicts who are an obvious danger to themselves. These holds are also out of favor in drug-normalized communities, and so police will turn a vulnerable drug user in crisis loose because the user declines help. With predictably tragic results.

. - Listen to recovered addicts. Harm reduction in its current form works for some drug users. It doesn’t work for others, however, and their voices should be part of the public conversation. Too often, harm reduction programs are pitched as if they represent the experience and aspirations of drug users generally, but people who have a deep history with the drug scene – and who aren’t pushing an agenda – know better. Drug use and recovery stories reflect a broad range of experience and that should be incorporated into the design of harm reduction programs.

Any community or facility using harm reduction programs should pause the expansion of those programs pending an evaluation of existing programs in terms of efficacy in terms of long-term recovery and integration with treatment providers. (Note: Don’t pause the programs, just the expansion of those programs.)

Conclusion

Handing out syringes in the late 1980s. Credit: Doug Wilson

One of my friends in recovery told me that when she was using, the first people to treat her like a human were the ones she met at a needle exchange. They brought her of the shadows, connected her with treatment, and put her on the path to recovery. That’s what harm reduction can be at its best, and that’s what it should aim for all the time. The harm reduction principle is as valid now as it was some 34 years ago, when that first needle exchange started operating at Point Defiance Park in Tacoma. The idea back then was to keep drug users alive and as healthy as possible while gently nudging them into treatment and recovery. It wasn’t a cure for the drug epidemic, but it worked well within its parameters and helped to broad base of support for the harm reduction model. But as the drug epidemic raged on and grew more lethal, government started throwing money at harm reduction (“the one thing that seems to work”) and began loading the program with ever more magical expectations. And waiting to take that money and indulge those fantasies was an army of public health idealists, bureaucrats, and drug-use advocates. You know the rest of the story. In three and a half decades, harm reduction has gone from an act of thoughtful resistance to a flag of abject surrender. Its motto is: If ya can’t beat drugs, join ’em. Some harm reduction critics say we should end these programs, but that would be another act of surrender, a forfeiture of something good that was hard-fought and won. Fortunately, there is a third way. Instead of junking harm reduction or leaving it in the hands of the pro-drug crusaders, we can take it back. And we should.

Appendix A

Trading Places: When the Government Is Your Dealer

Among the many things that make life difficult for a drug addict are high drug prices and inconsistent drug quality. If we allow that high prices and bad drugs are “harm,” it follows that making drugs cheap or free, or improving the quality of drugs, is harm reduction. Given that, it’s surprising that more harm reduction advocates don’t call for either legalization of drug dealing, all the way up to the narco-traffickers, or for having the government just give drugs to users. As it happens, Canada is already experimenting with that, at the Crosstown injection site in Vancouver.

The Crosstown injection site probably won’t be doing any long-term recovery studies. That’s because their clients have decided they don’t WANT to get off drugs. That’s not necessarily a bad outcome. If all their clients are maintenance addicts who don’t need to increase their dose and genuinely don’t want to get off the drug, the numbers will pencil out, because it will always be cheaper to buy these addicts their heroin than to pay the incidental costs of them using street drugs and stealing to pay for their habit. The thing about heroin, though, the thing that it makes it so hard for the addict to beat, is that drug steadily increases the user’s appetite for it. This is the phenomenon known as “chasing the dragon,” a combined physical and psychological condition where the user continually tries to recapture the overpowering rush they got from their very first high. But even as they approach that high-water mark, it seems to recede still further away from them, leaving them with an unquenchable thirst. Chasing the dragon is why opioid users on the street flock to the dealers who are thought to have a more potent batch of the drug, even if word has gotten around that the new batch is too strong and has caused several deaths. In one of the Crosstown videos, a client makes it sound as if the choice is between a safe supply of injectable heroin or the Russian roulette of drugs on the street. Including the notoriously dicey fentanyl. But that ignores the question of why addicts switched to fentanyl in the first place. They were chasing the dragon. How does the Crosstown clinic handle it when addicts ask for their dosage to be increased because their old high is no longer enough? Do they give in and let the addict steer the course of their “treatment”? Or do they turn them away?

Appendix B

Daredevils

This article typifies media’s shoddy or even deceptive reporting on the drug epidemic. In a several-hundred-word article about a dangerous new street drug called xylazine, the author never gets around to clarifying why the drug is out there in the first place. The implication is that evil chemists or drug dealers are dumping it into the fentanyl supply to kill addicts, but the truth, which I confirmed with a 5-second Google search, is that addicts have been seeking out xylazine because it prolongs their high. In other words, addicts WANT this stuff!

Appendix C

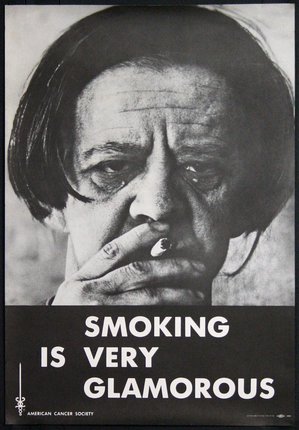

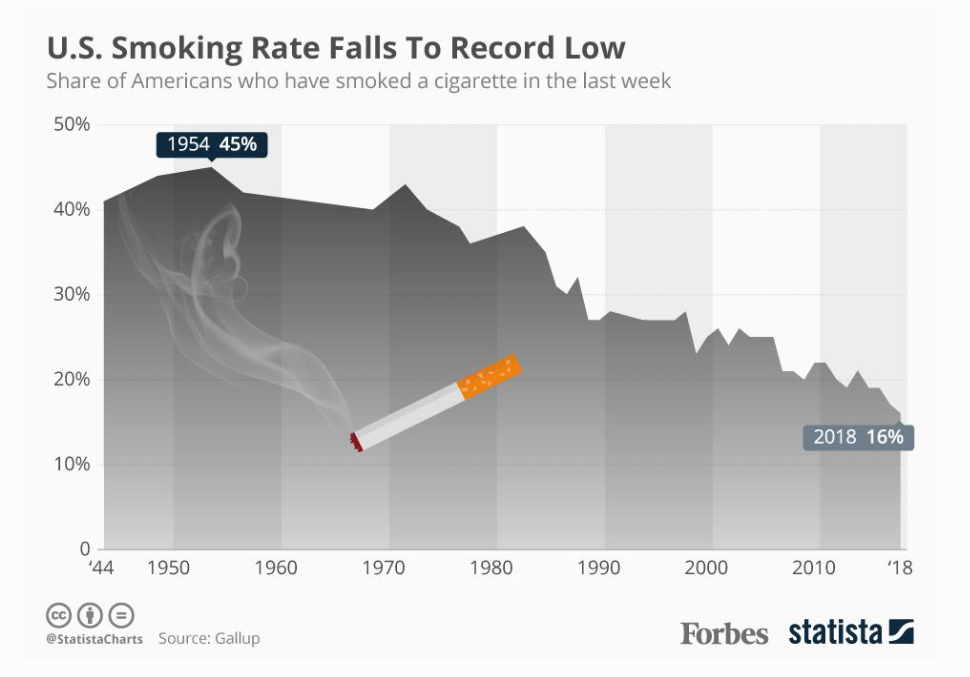

When Stigma Was Cool and Smoking Wasn’t

Do you remember that one time the government spent millions of dollars on gory advertising campaigns to discourage kids from using tobacco? And they required “WARNING: This could kill you!” labels on tobacco products? And one by one cities and states around the country started cracking down on public smoking? And then they started in with the “sin taxes” …

Do you remember that one time the government spent millions of dollars on gory advertising campaigns to discourage kids from using tobacco? And they required “WARNING: This could kill you!” labels on tobacco products? And one by one cities and states around the country started cracking down on public smoking? And then they started in with the “sin taxes” …  Then one day you noticed that there weren’t as many people smoking as there used to be, and the ones you did see were out on their porches in the cold and rain, looking miserable. This was an organized, decades-long stigma campaign designed to curb the use of a prevalent and highly addictive drug. And it worked. Yet now, in the face of all evidence, the harm reduction advocates are saying it doesn’t.

Then one day you noticed that there weren’t as many people smoking as there used to be, and the ones you did see were out on their porches in the cold and rain, looking miserable. This was an organized, decades-long stigma campaign designed to curb the use of a prevalent and highly addictive drug. And it worked. Yet now, in the face of all evidence, the harm reduction advocates are saying it doesn’t.

Click here or on the chart to read the Forbes article.

Oddly enough, if you do a search for studies on smoking and stigma, you will find several that claim that it wasn’t really stigma that made Americans quit smoking: it was tobacco taxes. But that is belied by the chart above, which shows a downward trend that inversely follows the upward trend in stigmatization. It’s also contradicted very specifically by the the CDC and others, who have claimed that ad campaigns – campaigns that stigmatize smokers by associating them with smoking with ugliness, pain, and death –are effective.

Nicotine addiction is different from addiction to hard drugs in important ways, and a targeted stigmatization campaign would likely not be as effective for people already deep into a narcotics addiction. But it might work with young people thinking about trying a drug for the first time. At the very least, we need to destroy the myth, propagated by Hollywood celebrities and musicians like Kurt Cobain, that drugs are cool.

Appendix D

A model study to correlate injection site use to long-term recovery

Once a sample group has been recruited from the injection site client base, each participant could be surveyed at frequent intervals with some simple questions like these:

● As of today, are you still using heroin or other narcotics?

● If you’re still using heroin, are you still coming to the clinic? (How often?)

● If you quit using heroin, how long has it been? (It’s OK to relapse)

● If you quit, how would you say the clinic affected your decision?

● If you’re still using, how would you say the clinic affected that decision?

Deaths within the sample group that are known to have been caused by overdose or another heroin-related health condition could be included in the analysis as well, and tracking this particular subset (those who die during the study) can be facilitated by having participants file a form with the the local medical examiner and police: “Please notify JOHN Q. RESEARCHER, MPH at [Contact Info] in the event that JOE H. HEROIN-USER is deceased.” Injection site staff would be blinded as to who is in the study. Participation would be anonymous and entirely voluntary and would not affect the participant’s right to access the injection site. Participants could be compensated with pre-paid phones or other minor inducements to get them to stay in touch. As described above, this would be a qualitative study to determine how participants thought the clinic had helped them get off or stay on heroin, but it could also be simplified to to be a quantitative study correlating long-term survival rates to injection site usage, with a similarly sized group of heroin users who did not use the sites as a control set.

All photographs in this post are property of the author unless otherwise attributed. * One thousand study participants would be just one fifth of the number of heroin users that Vancouver’s Insite injection room claims they served in 2019. ** The survey would be managed by an entity that has no connection to the harm reduction or treatment provider community and has nothing to lose or gain from the results. It could not be run like the so-called “one night homelessness counts” and homelessness surveys that local governments have undertaken in the past. Those surveys are done by volunteers who have no specialized training and who are often connected to homeless service providers who have an interest in showing that most of the people living on the street became homeless here.

The frequency of friends, but ESPECIALLY parents, calling my coworkers and supervisees at work for things that aren’t emergencies absolutely floored me when I started working in an office (I was previously a theatrical set carpenter, and trying to do this to someone who works in a scene shop would simply not work). Like, these people are at work, on the clock. People’s time is not their own at work (unless maybe it’s a worker’s collective), and I’m certain this isn’t some new norm that older generations never had to deal with. There’s a reasonable chance that the behavior will get this person you supposedly care about fired and left without a means of supporting zirself. Even at places like my office where this isn’t a strict fireable offense, extended personal calls aren’t exactly okay, either. I couldn’t believe anybody thought this was okay, let alone a large number of people.