Community Corrections Officers and Public Safety

Washington state doesn’t have either parole or probation for state prisoners returning to society. Instead, we have something called community custody, whereby a trained community corrections officer (CCO) will supervise a released offender for a variable period, determined by the court. During this period, which can run from six months to life, the CCO monitors the offender’s compliance with the court’s conditions of release and helps them transition back into society by getting them into job training, counseling, or whatever it takes. With community custody, part or all of the offender’s original prison time can be suspended, but there’s a catch. If the CCO finds the offender to be out of compliance with the conditions of release, he may send them back to jail for up to a month.

Roger Goodman is a Democrat representing the 45th District in the Washington state legislature. A 13-year veteran of the House, Goodman chairs the influential public safety committee. In late February of 2020, Goodman proposed three bills that would, if passed, drastically change the state’s community custody program first by cutting the time the average offender is subject to report for custody and by cutting some $50 million from the Department of Corrections’ community custody budget. This would force DOC to lop off hundreds of CCOs.

Roger Goodman is a Democrat representing the 45th District in the Washington state legislature. A 13-year veteran of the House, Goodman chairs the influential public safety committee. In late February of 2020, Goodman proposed three bills that would, if passed, drastically change the state’s community custody program first by cutting the time the average offender is subject to report for custody and by cutting some $50 million from the Department of Corrections’ community custody budget. This would force DOC to lop off hundreds of CCOs.

Goodman’s bills, which we shall describe below in more detail, caused an uproar in the corrections community. They had not been discussed with CCOs, their unions, or the communities across the state that they would affect. The first time CCOs heard about them, they had already passed through the Washington House and were on their way to the Senate.

Within hours of the news breaking, I was approached by a CCO I’ll call Terry and asked to interview him for an article. “We’ve got to get the word out that this is a really bad idea,” he told me. The next day I met him in a local cafe and we had a long discussion, which I’ve transcribed below.

–David Preston

David: What’s your background? What’s your stake in these proposed bills?

Terry: I’m a community corrections officer with the Washington State Department of Corrections. I supervise a myriad of cases, that come from some different jurisdictions. There are 25 in all and they include SOSA (Sex Offender Sentence Alternative), DOSA (Drug Offender Sentence Alternative), FOSA (Family Sentencing Alternative), CCJ (Community Custody, Jail, which denotes a crime that was sentenced often suspended but 364 days or less ), CCP (Community Custody, Prison), ISRB (Indeterminate Sentence Review Board – primarily used for sex offenses of an extreme nature), ICOTS (Interstate Compact, where a person commits crime in another state and lives in Washington so DOC supervises on behalf of sending state) and so on. These control both the prison custody and community custody sentencing guidelines, and each has a different system that we are expected to know. I have degrees in criminal justice and sociology with minors in psychology and have been working in social work and law and public safety for over a decade.

My caseload is primarily high-violent, high-violent property drug cases, because those offenders are at the highest risk of reoffense.

David: Do citizens generally know what you do and how important it is?

Terry: Not at all. In fact, on National Night Out this year, my team and I went out and contacted civilians the way police officers do, and out of over 100 contacts we made, not a single person knew what a Community Corrections Officer (CCO) was, but when they learned what we do and how we keep them safe, they were happy to hear that we were out there and around. We do not drive marked vehicles, and sometimes we are not geared up. Sometimes we are simply conducting field work and checking up on supervised individuals in public. But you may never even know that we’re there. We’re the ghosts of social work and law enforcement.

David: Tell me more about what you do and how it’s different from your counterparts at the Seattle Municipal Court’s probation office or the police.

Terry: Seattle Municipal Court probation officers primarily work in an office setting. They do not have arrest or warrant issuing capabilities. They do not conduct home visits on supervised individuals. But to me, if you truly want to know how an individual is doing, you go see them in their home environment. I can call someone into an office, sit down with them, and they can tell me anything they want, but I have no way to verify whether they’re telling me the truth.

Additionally, since offenders know that a municipal probation officer (PO) can’t arrest them, there’s no teeth behind all the carrots. Also, Municipal Court supervises only misdemeanors, so they’re not dealing with violent felonies, they’re not dealing with sex offenses. They’re only dealing with municipal offenses. A good portion of municipal cases read, “Shall supervise through DOC.” If a person already has felonies, a judge will often sentence them, at the municipal level, to municipal probation. But then municipal probation often kicks them to DOC and says, “They’ll be supervised through DOC,” because they know that we actually have some capability of effecting change. Additionally, we do it for about 20 to $25,000 less than what municipal court POs make per year. Oftentimes CCOs will leave for municipal probation.

On the comparison with police, we are similar to law enforcement in that, unlike Municipal Court POs, we have arrest capabilities. I conduct warrant sweeps where I arrest individuals on warrants. I am firearms certified like a police officer. I am Taser certified. I carry pepper spray… In fact I sometimes look very much like a cop. I have my ballistic vest with the word OFFICER on it. I routinely work alongside multiple agencies (federal, state, local) to get what I consider to be people who need getting off the streets and away from the community. We walk into high-risk situations. Oftentimes we’re even more at risk than the police because we show up unannounced. I can’t tell you the number of times I’ve walked into a house and I see multiple people there, and I’m there to contact one person who may not be in violation of [their release conditions] at the time. You walk into some houses and BAM, you see a gun on the table. Well then it’s a whole different ball game. But unlike police, we do not have radios to contact dispatch. We are out here on our own, flying solo. And we do it because we know what we do matters. Every day.

David: How do your powers differ from those of a police officer?

Terry: A police officer has a broad jurisdiction. He has jurisdiction over both you and I sitting right here in this cafe now because we are in public and if he contacts us for cause he has arrest capability over us. But as a DOC officer I have no power or jurisdiction over you unless you’re under my supervision.

We have a very broad range of jurisdictional powers over a very limited number of individuals who are earning their way back into the community. When under community custody or probation or parole, a supervised individual has a limited Fourth Amendment right. An individual working their way back into society faces multiple challenges and oftentimes faces temptations. My ability to interrupt a crime cycle is contingent on my ability to conduct searches (with reasonable cause). So, if I find meth in your pocket or you’re consuming methamphetamine and you drove here today, I might search your car, because I have reasonable, articulable cause that you are consuming or possibly dealing drugs. This has sometimes spiraled into me taking pounds of methamphetamine off the streets. It takes years, oftentimes, for law enforcement to build that kind of case. We stop it, and you never hear about it.

David: Why can you do that? Is it because regular law enforcement would have to surveil and get a warrant…

Terry: –and confidential informants, and do controlled buys. Let’s say I’m supervising you and I go to your house and you’re not expecting me. You don’t clean the place up that fast. It’s not possible. Also, we have the right to go wherever you are, as long as we have reasonable cause. So if you have a warrant out on you, and I locate you, reasonable cause becomes me asking, “What else is going on here?” My team and I have gotten guns, dope. We’ve interdicted sex offenders. I don’t know how much you know about sex offenders, but most of them are considered to have cyclic activity. It’s much like serial killing. They go through a phase, and if you interrupt that cycle, you stop the potential harm. So having the ability to do what we do is critical for public safety.

David: Tell me more about community custody. Why is it important? How many CCOs are out there doing your job and how have the numbers fluctuated over the years? Has it gone up or down?

Terry: Community custody can be court ordered by judges once you’re released from prison, but you can also be sentenced to community custody instead of prison. It’s sort of a hybridization of probation and parole. You can’t be sentenced to parole, but you can be sentenced to probation. So you’re released early with the understanding that you still pose a risk, and that’s where community custody comes in.

In determining how to supervise someone and for how long, we have a risk scoring system. We use an assessment tool called the WA-One. It asks a bunch of questions relating to criminal history. There’s static risk, based on the facts of events and what was going on in the life of the individual at the time, and dynamic risk, based on feelings, circumstances, and things that change with time or place. The assessment looks at everything and calculates a risk of reoffense score. Low risk means just that. High Violent or High Drug, High Property or High Violent Property Drug means that person is a high risk of committing those types of crimes again.

Part of what we do is we maintain accountability for court-ordered conditions. Conditions of release. We help give general structure to people’s lives after they’re released from prison. And if ordered by the court, the person will also have to go to drug and alcohol treatment. We maintain the accountability there, and we say: Are you actually doing what you’re supposed to be doing? OK, let’s see some documentation. If you’re not, we have recourse. We can sanction you. Because what we’re finding is that people will say to a judge that they’ll do a lot of things, but then they don’t do them, and without us there’s no recourse. The court does not have time to hear about every person who does not go to drug and alcohol treatment. We monitor law-abiding behaviors, too, so if I’m contacting you and contacting your family, and you’re getting rave reviews and you’re really trying, I’m able to go to the court and say, “Hey, he’s doing really well. This is awesome. This is good.”

We assist with jobs and finding housing. DOC will pay for three months of clean and sober housing for people being released from custody. We have hundreds of resources and connections for jobs. I don’t personally connect people with a job, but we have a guy that comes in every week and he specifically scouts out jobs that are felon-friendly. He will provide the released offender with lists of job contacts, helps them write resumes.

If you want to go to training, we will pay for that. We will monitor that and say “Hey, you’re going to school.” The court has what they call affirmative action. That’s where somebody comes in and they have a paycheck that says they’ve been working 40 hours with 10 hours of overtime. And I say, “Awesome. You did great. This week is awesome for you because I can account for your hours. You’re not sitting around doing nothing. If you want to go to school. I won’t force you to go to school.” And most oftentimes they do. But if you’re in school, I will monitor it. “Hey, how’s school going?” I’ll ask you. And you might say, “Oh, I’m really struggling. I had to drop my job.” And I’m like, “OK. Let’s find you some resources so you can cover your rent for this month because you did take on a pretty intense training program.” We have the ability to give these people references and help them get all of those things.

David: That’s not what most people would think of as affirmative action.

Terry: I don’t think they mean affirmative action in the same way that you think of it normally, but it’s behaviors affirming of your intent to lead a successful life, and so by bringing me a school schedule or by bringing your grades every semester to show that you’ve been going. Rather than me sitting down there grilling you, like, “What have you been doing with your time?” every week, I get people into things so their time is automatically accounted for. If you worked 60 hours this week, I’m not gonna get on ya about what you did on your two days off.

It’s about reestablishing positive relationships. Oftentimes we are able to help families reconnect, because if the family doesn’t trust this person, and they’re calling me saying how is he or she doing? And I say, “They’re going to school, they’re doing all this good stuff,” and they’ll say, “Oh. Maybe I will reach out to her again.”

But on the flip side, we’re also able to say [to the supervised individual], “You’re not doing anything with your time, so I must assume that you could be getting into trouble. If you have no job… If you’re living God knows where… If you’re not engaging in anything positive… If your treatment provider says they haven’t seen you in three months… then I begin to wonder what’s really going on there. Maybe I tighten up a little bit and bring you in. Let’s say you stop reporting every month. Ok then, maybe I have you start coming in every week. Or maybe I call you on the spur of the moment and say, “Where you at? Stay right there. I’m coming.” Maybe I get to know your associates and your friends…

David: Do you think the taxpayers are getting a good value for the money with community corrections officers?

Yes. From what I read and see in the news, the public keeps saying they want accountability. They want “community service officers.” You have that already, right here, with me. Only you do have to be convicted of a felony first, or enough misdemeanors that it gets you to DOC. But otherwise, I already do all the CSO stuff. If you’re not engaging in treatment and continuing to use controlled substances, and it’s clear that you’re not rehabilitating, I may take you into custody. My holds are “no bail” so you’re not going to get out in 24 hours. You’re going to have a longer time out.

But it could also be self-directed, where somebody says to me, “Hey, I know I’ve been screwing up a lot. I want to go to treatment.” I can refer you, then and there, and pay for transportation. I saw a news story last night about how the community doesn’t pay for transportation to treatment. Well DOC does. We’ll put you on a bus direct. Sometimes people will call me from jail and say, “I wanna go [to treatment].” I will arrange pick-up and a release date, directly. You can walk out of King County Jail and the treatment bus will pick you up right there. And we will pay for that. And you can stay there as long as you need, up to six months.

David: Does all this really translate into improved behavior?

Terry: Sometimes. Again, it’s up to the individual. I can lead horses to water all day long. I can offer you various springs to drink from. I can’t force you to drink from them, but if you don’t, and your behavior becomes criminogenic again, we can go right back to the barn.

David: So do you have a sense that you’re making a difference in the lives of people?

Terry: Yeah. Every day.

David: Give me some examples of that, without mentioning names or other personally identifying info.

Terry: A good example would be today, where I got a call from a guy I supervise. He’s kind of struggling right now. And he said, “You know, you gave me a lot of tools, but I need to ask for some advice and I need to know if you can help me find some other things to utilize.” I said, “Absolutely.”

David: So this is an ex-supervisee? You didn’t have any power over this guy? He just came to you?

Terry: Yes. It’s not uncommon to have formerly supervised individuals come to me with asks. I get calls from guys who are doing great. They’ll say, “Hey I moved down to [redacted] in southern Washington, and I’m running a job site right now cuz while I was on DOC, I got into the PACT/ANEW program. My wife and I just bought a house and I wanted to tell you thanks. Thanks for hooking me up.”

David: The people you deal with who have difficult behaviors, like violence and sexual abuse, do you ever see them change?

Terry: Yes. That’s the population I work with right now, and it’s somewhat less successful, but there other reasons why I think that happens. But the short answer is yes some of them get better, because everyone is capable of change. But people seem to think that everyone wants change, and that’s not necessarily true. You have to want to change, and that’s the piece that I can’t give an individual is the want.

David: Some people perceive you as an agent of the state who harasses those who have done their time and have been released.

Terry: I get that all the time, and what I ask these people is: “Do you think the people I supervise would be doing better without me?” And they usually say, “Well no, but they wouldn’t be doing any worse either. And society isn’t any better off.” And my next question to them is: “Oh really? How are they supporting themselves? Is it truly a victimless crime when they’re out dope dealing and maybe selling fentanyl to a high school kid who then ODs? Is it a victimless crime when they’re living in flophouses?” And that makes them think it over. And they still don’t like us, but then, they don’t like the police either. They want us to be social workers, which we are, but we wear two hats, really, and it’s one of those deals where when you switch the hat from social worker to law enforcement people like you less because suddenly you are the hard stop, you are the accountability. And let’s face it, some people just don’t like to be held accountable. They wanna do what they wanna do.

David: You see yourself as a social worker as well as a law enforcement official? Talk more about that.

Terry: Every day I have people that call me up for advice. I helped a guy recently who’s young, and he’s got quite a few felonies under his belt already, but I keep him trying. He called and said, “Can you stay late? I need to fill out a job application, and I don’t know how to do it.” He’s never had a job before. And I did stay and help him. And he got the job. And I’m so frickin’ proud of him.

David: Is this something that people who challenge you with the harassment thing just don’t know about you? That you’ve got this dual nature of a being an enforcer but also a helper?

Terry: Yes, some of my supervisees think that, too, and if they haven’t seen the social worker side of me it’s because they’ve never enabled that side of me, even though I’ve offered it to them. I put on whatever hat you present to me as needing, so if you come to me and ask for help, I’m going to help you. I can’t tell you how many times I arrest someone, they get out, they report again, they start talking about Where did I go wrong? What can we do differently? They bring it up, not me. I have a guy I’ve arrested and sent to prison, and his mom will still tell you to this day that he respects the hell out of me because I didn’t cave in to his puppy eyes. He’s been calling from custody and saying, “OK, will help me fill out this application for this program. Will you help me get in it? Will you write me a recommendation?” I said, “Yes I will.”

David: Sounds like you’re being a stand-in parent for some of these folks. The mom or dad or stable uncle they never had growing up.

Terry: Absolutely. A lot of times it’s that people didn’t have the structure, and I’m familiar to them [as an authority figure] and so they instinctively fight it. I didn’t have structure growing up myself, and so I’ve always been more on the structure side. But unlike some of my supervisees, I went the opposite way from how I was raised.

David: If these bills are passed, how’s that going to affect you and your colleague? How will it affect the state as a whole?

Terry: My office alone, which is a small office, supervises 400 to 500 people who are active in the community and are on supervision for an array of offenses from murder down to property crimes, and we also have a couple hundred offenders on warrant right now that we’re trying to find, so if you take that one office times the many in the state, you’re looking at from 15 to 20 thousand people active in the community being supervised. How much do you know about your neighbor? I’m not saying that your neighbor is an offender, but they are out there, and sometimes people just need a little extra supervision to get going.

Often we help families reconnect. If the family doesn’t trust this person, and they’re calling me saying, “How is she doing?” I can say, “She’s going to school, she’s doing all this good stuff.” And they’ll say, “Oh. Maybe I will reach out to her again.”

David: The bills as proposed wouldn’t eliminate your office or any other office, but they would cause a reduction. Is that correct?

Terry: It would be a devastating blow because how then do we do our job? They’re deciding based on a blanket ruling to drop hundreds or thousands of people off supervision. That’s something that we do on an individual basis only after careful consideration, using a case plan that highlights the person as an individual, with their individual needs and triggers. But now our department is trying to force a mass release from supervision at the cost of public safety. It’s basically saying everybody whose current offense is x-y-z will be dropped.

In California they did away with several crimes as post-release supervisable offenses because they weren’t deemed violent anymore. And Washington has done it before too.

David: Crimes such as?

Terry: Robbery 2 is no longer considered a violent, “strikeable” offense, as in the “three strikes law. But if you’ve ever seen what a Robbery 2 looks like for that individual victim.

David: What does it look like?

Terry: There is violence. There are threats. There is fear. There are weapons. There can be assault. In the most recent one I saw, the individual who was robbed was absolutely terrified. To me, if you do that to someone for personal gain, in an illegal activity, and for that not to be considered violent? It’s wrong. And in this particular crime, two individuals were struck hard in the face with the butt of a gun. And you’re telling me that’s not violent? That’s violent! And let’s say they plead that down even further. Maybe they get assault 3 with burglary or something like that. Now they’re going to be supervised at this low-risk level. This person’s willing to engage in highly violent activities, but we’re going to supervise them at the same level as somebody who walked into a café like and said, “Give me your recorder, dude” and you hand it over to them. That’s not OK.

David: These proposed bills seem to have come from the top at the Department of Corrections. I don’t think the legislative sponsors came up with this on their own. What happened there?

Terry: I wish I knew. We were blindsided by this.

David: When did you find out about it?

Terry: Last week.

David: Do you know when the bills are scheduled to be voted on?

Terry: I honestly don’t. I’ve heard that they’re most of the way through, and I’m still wrapping my head around how that could happen and what they were thinking. This is terrible. Even our union was blindsided with it. To me it’s pretty shady on the part of Representative Goodman as well as our own department. Our department is sacrificing public safety for some money. That they’re going to do what with?

Often we help families reconnect. If the family doesn’t trust this person, and they’re calling me saying, “How is she doing?” I can say, “She’s going to school, she’s doing all this good stuff.” And they’ll say, “Oh. Maybe I will reach out to her again.”

David: What union represents CCOs?

Terry: AFSCME and WFSE.

David: Are the unions planning a response to this?

Terry: They’re scrambling now, begging us to tell all our families to call their legislators to tell them to vote no. But again, we’re so far behind the curve here, we didn’t even know that this was coming, all these proposed bills. And they were not even gonna put this out to the public and were trying to sneak this through. I don’t know if you remember this from the last session, but almost every bill that they tried to sneak through without a public vote didn’t pass. They’re still trying it anyway though. It’s alarming.

David: I assume no one from DOC upper management asked you or your colleagues for input.

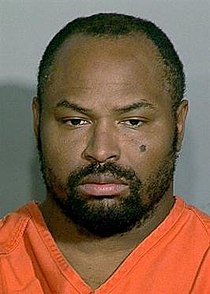

Terry: Not at all. In fact, now that people have blown the whistle on it, they’re spinning it as, “Oh your caseload will be reduced. Don’t worry about it.” My contact standards are through the roof and it’s hard, but reducing my caseload is not going to make for a safer community. I would rather work harder than to not be sure that things are being done correctly and then lose track of people. We had cutbacks in 2009 and Maurice Clemmons is a prime example of what happened then. There were 16,000 offenders dropped off supervision and cases were missed because CCOs were dropped, cut, and laid off. And field files, which is what we call the paper casework, were shuffled around and offenders got lost in that. I mean it’s already hard enough not to have people slip through the cracks, but imagine that you suddenly have gaps in CCO coverage. Wide ones.

Maurice Clemmons was a released offender who was “in the wind” after the state legislature slashed community custody resources in 2009

David: I remember Clemmons. Vaguely.

Terry: Maurice Clemmons killed the Lakewood Four (police officers in Lakewood Washington). His case had been shifted around in the scramble of layoffs. CCOs were being transferred and moved around and they ended up supervising cases that they were familiar with. We do get a really good level of familiarity with a lot of our guys and their families over time. And even if they do go on warrant and we don’t know where they are, we’re pretty darn good about flushing them out.

David: Clemmons got dropped from supervision?

Terry: He was not dropped. However, his case had gone through so many hands that nobody had had time to familiarize themselves with him or his habits or who he was. Maurice Clemmons was in the wind.

Clemmons murdered these four police officers at a coffee shop in Lakewood Washington

David: And that happened because of CCOs getting laid off?

Terry: Yes. Sixteen thousand offenders were cut in 2009, and I don’t know how many CCOs. But CCOs were definitely cut and 16,000 offenders just went POOF, gone, suddenly nobody knew what they were doing. Clemmons wasn’t dropped but his case was shuffled from one to another to another to another. And it’s like the game of telephone, where by the time it got to the tenth CCO or however many it was, he got lost and nobody knew where he went until he resurfaced at a coffee shop like this, and four police officers lost their lives. I’m not saying it was preventable, but here’s the thing. I may not always know where my guys are, but you better believe I hear chatter about what they’re up to, and I’m putting that out to multiple agencies. We can’t prevent everything, but I at least know the guy’s on supervision and not just a random field file that’s suddenly thrown on my desk with ten others cuz they laid off 200 CCOs.

I would ask them about that $50 million dollars they think they’re saving. I would say, What is your community worth to you?

David: Are you saying that kind of thing might happen again if these bills are passed?

Terry: Yes. I am confident that that will happen.

David: Is your job in danger?

Terry: I don’t know. They tend to do last hired first laid off, so maybe not. Or maybe yes. It depends on where I fall in that first round. But it’s not about me; it’s about the community. It’s two years before the next cycle of our contract comes up. That’s not enough time to assess the damage. In 2009 they had these big layoffs and they tried to recover, but they didn’t start restaffing and reupping until 2014, so five years passed and things went pretty tanky before they started beefing up CCOs again.

You asked how many we have statewide. Right now we have 1,000 to 1,200 give or take. And that number has fluctuated. They dropped two or three hundred in 2009. And they were saying the same thing then that they’re telling us now, “Your caseload just got lower, don’t worry about it.” It did get lower and that’s great if you’re a pencil pusher or you’re an accountant, but at what cost to everyone else?

David: Ahhh. Is it the accountants pushing this?

Terry: I don’t know. I don’t know who’s in charge of this or who thought this was a good idea, but I’d sure like to sit down with them, cuz I don’t think they’ve ever walked a day in my shoes.

David: Is it political?

Terry: I think so. I think it’s absolutely part of the police reforms that are happening in Seattle and statewide, and I’m not saying reform isn’t necessary, but along with shortening sentences, we’ve taken away a lot of time that prison has to change offenders and make them better. They talk about prison not reforming people, but defense attorneys love to drag out trials so they’ll drag them out for the two years maximum, so the accused has already spent two years in jail. Now you get to prison and you’ve got just six more months there. It takes six months to get into a [prison-based] program. You’re not gonna make it. You come out in the community having nothing. Nothing. Prison actually has been able to help people, but you need the time. And then you need the actual support afterwards in the community, and that’s where DOC can be very supportive. People don’t think that community supervision works, but if I’m offering you avenues to better your life and you’re not taking them, whose fault is that?

David: Maybe the bill’s sponsors are thinking that you can be replaced by a diversion program such as LEAD.

Terry: I believe they are. I think that’s kind of what they want my program to go to, but LEAD has not historically been doing fantastic. They say they reduce recidivism, but just because crimes aren’t being charged and people aren’t being jailed doesn’t mean you have reduced them. We interrupt crime, sometimes forcefully, by arresting someone and stopping it. Sometimes that needs to happen but LEAD can’t make it happen.

David: You said the people you supervise are high violent. But that’s not true for the people the LEAD program supervises, is it?

Terry: Lots of high-violent people get referred to LEAD because they get referred for the instant [most recent] crime. They’re not looking at what the person’s full criminal history before sending them to LEAD. So yeah, I can tell you, I have people who are involved in the LEAD program who are DOC-classified as high-violent because of multiple factors in their history. Without going into too much detail, there are felony assaults, rape…

David: So that history is not taken into account when making the decision to put someone in the LEAD program?

Terry: Not that I’m aware of. If it is, I don’t know about it. I just know that I have people with lengthy criminal histories, and they’re getting in the LEAD program and they’re still doing that stuff. Why? Because a LEAD case manager is not going to come to your house. They are not going where you are. They are staying in an office and you [the offender] are coming to them. If I’m an offender, I can present very well in an office. I don’t know if LEAD even gives UAs [urinalysis tests for drugs] but if they do, they’re not observed. Nor are treatment UAs. You’d be surprised by the number of people who laugh about the fact that they get away with surreptitious drug use everywhere but DOC, because we stand in there and watch you pee. It’s awful. But… you’re not gonna be able to slip some fake pee in there either. DOC is a hard stop, and that is why people don’t like us, because we are… a wall.

For an article about Representative Roger Goodman’s

support of the LEAD program go here.

David: Let’s go through these bills one at a time. The first one I’ve got here is SHB 2394. It’s requiring that community custody terms will run concurrently, rather than consecutively. This means that offenders will spend a lot less time overall in your care. Tell me why you think that’s not a good idea.

Terry: There’s no failsafe built into it. We know in about six or seven months whether a person needs lengthy supervision. They haven’t enabled an easy pathway for us to position for that either, but what they’ve done is to give way less supervision time. So what if it’s been six or seven months and we’re like, “Oh no. This person is definitely not amenable to community custody and they need a lot of accountability.” We have no recourse there. They’re just done.

2394-S-SBA-HSRR-20David: How long is the ideal time in community custody for a high-violent offender?

Terry: That depends on them. Everything is dependent on the individual. Let’s say we have a guy who commits a robbery 2 in Snohomish, which is a violent felony, and he’s not picked up on that yet but there’s probable cause for the police to arrest him, and then he commits a robbery 2 in Seattle, and he’s not picked up on that yet, and then he goes on to commit another robbery, in Pierce County. And he’s caught and charged with all three crimes, but they’ll do what they call a global sentence, which is where each jurisdiction sentences him. As part of these jurisdictions he gets x amount of prison time, and he gets x number of community custodies, so when he gets released from prison, however long that sentence turns out to be, he has three separate community custody sentences.

“People laugh about the fact that they get away with surreptitious drug use everywhere but DOC, because we stand in there and watch you pee.”

David: …that are going to be run consecutively. One at a time.

Terry: Yes. They’re based on the time of the crime and the time of the sentencing, and they’re based on the fact that these were three separate events. This was not one event. But with this new bill, he’d now be serving them concurrently, all at the same time. So it would be 12 months instead of 36 months. Poof, two thirds of the crimes he committed are effectively gone.

David: So now the person has 12 months instead of 36 months? And you’re saying that that’s not enough for you to work with?

Terry: We’re also losing the revocable time, which we can effectively add back in to their sentence if we decide they’re not making any progress. What if it’s seven months into his community custody and I’m still not getting compliance? I’m spinning my wheels. Now we only have a few months left with that offender. What if he needs to go back into custody for a longer period? I have no recourse. The community, the victims, have no recourse. Now again, I’m all for an easier pathway. If he’s doing great and this was his wake-up call and this was the time that he got it, I have no recourse to say, “Hey, let him off, he’s good.” [I’ve lost the ability to reward as well as to punish.] Either way it’s a blanket bill. It doesn’t give the CCO any [options]. And who knows this person better? The CCO or the person up in Olympia who’s making these blanket policies to release people from community custody?

David: You mean blanketing in the sense that it treats all offenders the same, correct? It cuts everyone’s time down, regardless of their individual progress or situation.

Terry: Yes. With absolutely no justification for why they’re doing that. So if I want somebody to get off community custody early and I have a reasonable pathway to do so, I would have to justify why. Well, the legislature is proposing to do that same thing only with no justification. They’re putting the community at risk because they don’t know how this person’s going to behave when they get out. Not only that, did they get resources in prison? I can tell you that most prison sentences doled out by this state do not even give them enough time when you factor in “good time” [time off of a sentence for good behavior in prison] to get resources. Even just to complete a training program.

David: This bill is supposed to save $24 million. Sounds like a lot of money.

Terry: It sure does, but what’s your community worth?

David: A hundred CCOs will lose their jobs if this passes, according to my information.

Terry: I bring forth, once again, the example of Maurice Clemmons, who killed the four police officers after he was effectively dropped from supervision because of staff cuts. What about the shuffle there? You’re gonna lose a hundred CCOs, and a lot of people will drop off supervision too, but not the balance might not be in favor of the CCOs and the caseload might actually go up. So the CCOs left behind are going to absorb those additional caseloads. So you’re a CCO who gets laid off and all your cases that don’t get dropped come to me. Maybe I don’t know your guys that well and I don’t have time to get up to speed with them. Maybe some of them become field files lost in a corner. Like Clemmons was.

David: Next bill. SHB 2393. It allows a qualifying person to earn supervision compliance credits and reduce their term of community custody. That means they’ll be getting time off of supervision for good behavior, on top of any time they got off of their original sentence for good good behavior….

Terry: If you do your 30 days and you didn’t get any violations then I’m fine with you earning some credit off. But every day that you’re in the community if you’re not following the court-ordered conditions of this treatment, if you’re being arrested by other agencies, if you’re being referred to LEAD on a daily basis you are not in compliance. Why should you get credit for that?

2393-S-SBA-HSRR-20David: It does say in the summary here that they would only get their credit if they are in compliance with community custody conditions.

Terry: I see these people two to three times a month sometimes less than an hour each time. If this person is unemployed, if this person is doing all these other things, I don’t actually know that they’re in compliance. You’re not giving me enough time to develop this rapport, to even know that the baseline would be off. How long does it take you to get to know someone?

David: So you’re saying they’ll do their good time and get off of community custody early before you can form a relationship with them and have a sense of whether they’re in compliance or not?

Terry: I’ve had people do really really well for 11 months, and then on month 12 I stumble on them in a dope house they frequent because I was there for someone else. Should they be given credit for the rest of the 11 months when I bust them with two pounds of heroin that they’re dealing? Or should I have some kind of recourse where I can say, “No, we’re not ready for you to get off of supervision yet.”

David: Wouldn’t you have the option of taking way their “good time” and extending their time on supervision if you caught them in a dope house?

Terry: You would think that, but judges and historically DOC do not remove good time. In fact, I’ve had judges literally say, “I’m not sure I can revoke good time,” which makes me want to flip tables.

David: Even when the offender was clearly not in compliance?

Terry: Yes. Hands down. I do not take lightly removing someone’s freedom, but sometimes it needs to happen, and sometimes you need more time with them. Sometimes people get off supervision and totally flounder because they don’t know how to be accountable to anyone and this was the thing keeping them accountable. But again, you don’t know that if you’re automatically giving them good time. Couple that with the other bills you mentioned. Someone getting out of prison might have one year of community custody [instead of two because of two terms running concurrently] but because of this new bill community custody just got cut down again and now it’s eight months. As a citizen, how do you feel about that? Is that enough time? There’s a reason these bills are being put forth together.

David: The last one is SHB 2417. It allows sanctions for low-level violations to be non-confinement sanctions and allows a person’s sixth and subsequent sanctions to be optionally considered low level, instead of the current policy, which is, I guess, to consider them high level, which triggers a return to custody. To me this sounds like it’s giving you flexibility and cutting through red tape. You won’t have to consider the sixth low-level offense as a high-level one.

Terry: Let me put that back on you. How many times should someone get to violate conditions of the court that were imposed when they were released early? And what do you consider to be a low level?

2417-S-SBA-HSRR-20David: It says it’s giving you the flexibility to decide that.

Terry: In reality, it’s taking away the teeth that we have. Right now, especially in King County, what we have, is all carrot and no stick. We are the last bit of teeth. It’s triggered at the sixth time someone violates. Let me put this in practical terms. Let’s say I have someone who steals cars because they have to support a meth habit and they have been using meth consistently, and I’m saying “Hey, it’s the sixth time you’ve done this.” CCOs would actually like to be able to bump the sanction up for that, not down. We would like to put even more teeth into it, to where we could say, “You know, if you do this again, it’s not gonna be just 30 days. I might pull 60.” Sometimes that’s enough to keep people in line. And they’re going “Ehhh, it’s not worth that.”

I have literally had individuals I supervise tell me, “I can do three days. Screw you. It’s nothing.” They’re taking away a lot of discretion, and I mean, at the end of the day, if a CCO is burned out or they have given up, what’s gonna be the easier route? To do more paperwork and put them in for longer, or to let them off? Right now our policy says we shall [treat the sixth low-level violation as a high-level one]. If you change that to a may, the revolving door is going to get worse and worse and worse.

David: So you’re saying that, because of this bill, you will be encouraged to see the sixth offense as a low-level one. It also has a provision for third party review to see how many of these offenders you let off the hook for the sixth offense.

Terry: I already can view the sixth offense as low-level if I want. So if somebody is engaged in treatment, and it’s verified that they’ve been going and going back to jail would interrupt that, and I’m able to get in touch with their treatment provider and we can discuss it as a group with wraparound care I don’t have to arrest them on the sixth low-level violation. I already have the discretion to do that, but what about the people who refuse to engage? Now you’re taking another tool away from me, saying to the offender: “Well you’re not engaging in anything but, eh, it’s really not a big deal.” Never mind the fact that they took a reduced sentence and agreed to follow the court’s conditions, but they haven’t done so. And now? Meh… no biggie.

I already have the carrot and the stick, but the people who are not engaging, I’m not giving them a carrot, but that’s what this is. It’s a carrot for nothing. And it takes away the fear. And it’s not that I want people to be constantly in fear of being sanctioned, but sometimes I do an intake and we sit there and we talk about the level of consequences. Man that sixth violation gets scary. Along about violation number four, they start asking, “How many have I got left? How many before the real teeth come out?” And I say, “You only got one left,” and they go, “OK, OK, I’ll go to treatment.” That’s a big incentive, but now they’re taking that away from me, because why would I bother justifying why I decided to treat the sixth low-level offense as a high-level one?

David: The bill also mandates that new “Underlying 21” offenses cannot be used by a CCO to return someone to custody if the prosecuting attorney notifies DOC that they’re not going to be charged for the new crime. Some examples of “U-21” offenses are assault 1, assault of a child, burglary, child molestation…

Terry: We have an active bunch of prosecuting attorneys, but they are hampered by time constraints. They’re overwhelmed. So say I catch one of my supervisees in the act with a firearm or dealing dope, and charges can’t be filed in time. Bye! They’re back out on the street. It’s the revolving door again.

I would toss this back to DOC and the legislature, who removed some of the items from the list of violent offenses, and say why? We don’t even have the Underlying 21 anymore. It’s more like Underlying 18. They said assault 2 is not violent anymore. And the Underlying 21 is what you’re charged with, it’s what you’re convicted of, so that assault 2 might really be an assault 1 that was plead down. So you have very very violent people released on non-violent offenses, and they’re no longer anything. How’s this working out for us?

Plea bargains move the seriousness of offenses downward. This results in truly violent offenders often being classified as non-violent, which in turn skews the data and supervision time as well as prison sentences. The community ultimately pays that price and the victims even more so. Domestic violence is often, for example, assault 4, which under the strikeable offenses is non-violent. Robbery 2 we talked about now being considered “non-violent,” despite the inherent violence written of it as defined by the RCW. I’d like your readers to understand that this lessening of offenses results in the public getting data that suggests violent crime is down when it’s not. And their conclusion is therefore we are over supervising people, and this is simply not the case.

David: Which one of these bills are you most worried about?

Terry: I’m worried about the fact that they’re put together as a package. I’m worried about all of them together. Any one of them, put together with the others, will be catastrophic for communities. I can’t tell you how often victims contact us as CCOs. They’re terrified to go to police, but, as a CCO, I might be able to remove an abusive partner. Maybe someone tells me that their boyfriend who is under my supervision has been using meth…

David: Why are they afraid to go to the police?

Terry: Because they know the police cannot intervene. They have no options. But [domestic violence] victims call me, and they say things like, “He’s been using meth and I’m really scared. He threatened me last night.” Well, I don’t have to tell the individual how I know that, but what I have the authority to do is call him in for a UA. Maybe I need to hold him longer than three days.

Yeah. Or they’ll tell me, “He’s gonna be here at this time. If you show up, he’ll have a gun.” I show up, arrest him, and I get him and the gun off the streets.

David: Do victims know that you can do this when they call you?

Terry: Victims will often come to me instead of police, because they know I have the ability to keep them anonymous. And I can work faster. More efficiently. I have the ability to work with law enforcement without being the patrol guy who has to put it all in a report. A lot of times people don’t know where I get the information, and I don’t want to give up where I get my information from. And I don’t need to, because if I can go there and verify it, then I know that it happened. I can testify to it personally.

David: What can the average citizen do to stop these bills and help you do your job better?

Terry: The first thing you can do is to call and email your legislators, because the legislature is not even putting this up for a public vote. I’m pretty sure they were hoping this wouldn’t be leaked to the public. If our union just told us about this last week, that’s pretty alarming.

David: When people call their legislators, what should they say?

Terry: They should say they would rather have a safer community than to save a few dollars. The state has a surplus of cash. I’m pretty sure a lot of what they want to do with this money is to funnel it into programs that are not evidence based. DOC uses evidence-based research, and evidence-based sanctioning processes, and evidence-based programs and cognitive-behavioral therapy. And now they’re gonna take that evidence-based model and say, “Nah.”? Would they do that if it was climate change? That’s evidence-based, right? Would they throw climate policy out the window? -because that’s essentially what they’re doing with community custody policy. And I would ask them about that $50 million dollars they think they’re saving. I would say, What is your community worth to you? We have no clue about what they’re going to do with the money they save, other than that they’re gonna try a whole bunch of new things, and most of them don’t guarantee any safety for victims or any recourse for CCOs in supervising individuals at risk of reoffending. It’s just adding more carrots to a ripe field of them.

Another thing citizens can do is when they see us out (because we’re usually marked, the vest says DOC) come up and talk to us. I will happily tell you what a DOC officer does. I give suckers to kids all the time who think I’m a regular police officer, and I don’t always correct them. Come up and talk to me, and if you have questions about who’s in your area or what we do or what resources we offer, we’ll tell ya. I am always happy to talk. We’re out and about and if you saw us in uniform, you’d probably think that we’re just regular police.

David: Do you do ridealongs?

Terry: We do not, mainly because of safety risk. We contact individuals and things can go sideways very quickly. They say they want to save $50 million, but they can’t even spring for radios that connect to Dispatch. I ask legislators considering this, would you walk into a house filled with gangsters and guns and no radio to Dispatch? Cuz I do. If they’re not going to add money to our budget, they at least shouldn’t be taking it away.

David: Anything else citizens can do to help?

Terry: Report things. If you know someone’s on DOC, which a lot of people actually do, you can contact any DOC office (Google’s a beautiful thing) and if you know the person’s name, we can probably find them. If you know that something’s going on, tell us. If you want to report that they did an awesome thing, that’s cool, too. I need collateral contacts every single month. If you want to call me and say, “Hey, my neighbor’s doing great, he’s cutting his yard and he looks really healthy,” awesome. When you see me stop by his house, tell me that. You’re a collateral contact; you’re helping him succeed, you’re helping me articulate getting him off supervision sooner. But on the flip side, if you call me up and say, “Hey, he’s got people coming over here all hours of the night and his house got shot up the other night but I was too scared to call the police,” then tell me that too. You can do a lot as a citizen.

David: Parting words?

Terry: I think that these bills are too blanket and as much as we focus on diversity and individuality, these bills would not allow me to focus on the individual. They are offering everyone the opportunity to slip through the cracks, instead of letting CCOs build a relationship and a rapport and then making an informed decision. They’re doing that supposedly to save some money, but at what cost? At the cost of community safety.

Did you appreciate this article? Do you support honest journalism? Then please …