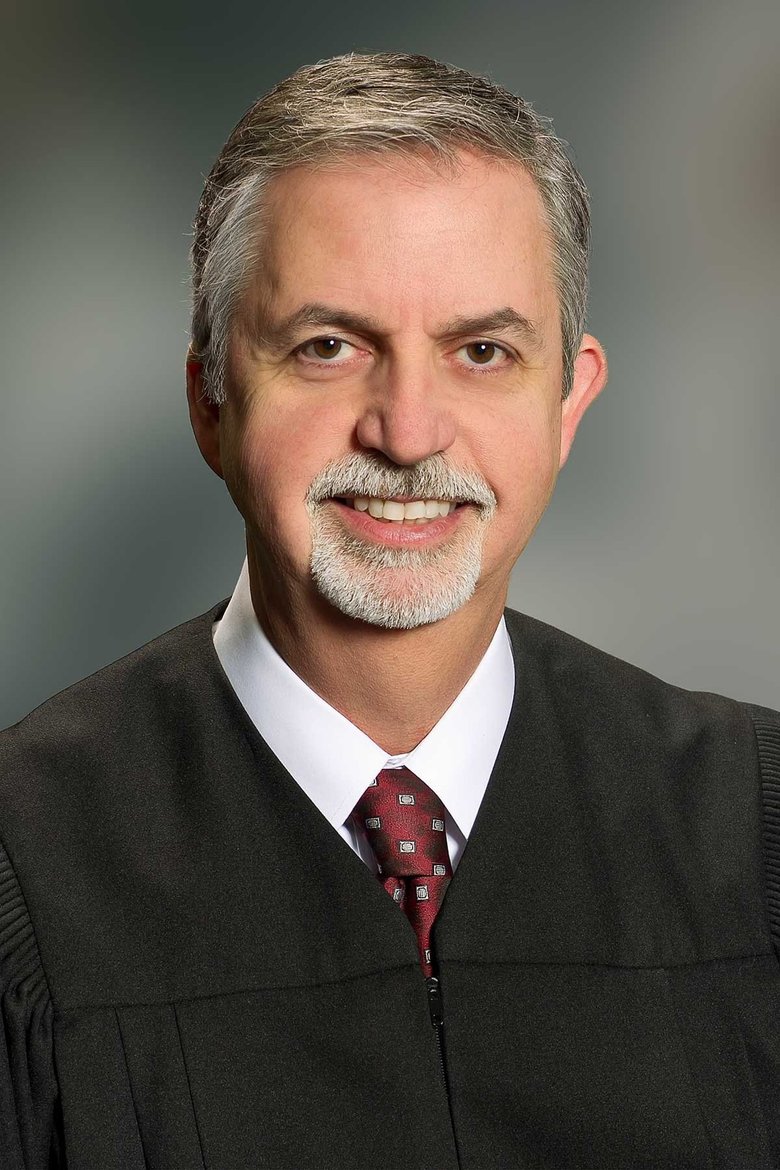

Dedicated to the Honorable Ed McKenna

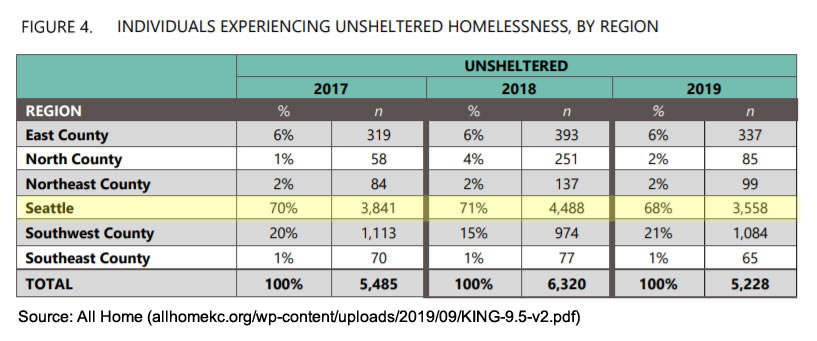

The glitter of Seattle’s economic miracle has rubbed off. There’s more money here than ever, but with money comes problems that money can’t solve. Homelessness is one. According to a recent “one night count,” there are some 4,000 people living unsheltered in Seattle, making us third in the nation overall and first per capita. People are living under bridges and in tent camps and RVs all over the city, and many of them and struggling with drug use and mental illness. Some are committing crimes.

There isn’t enough jail space to hold all those who are committing felonies, to say nothing of those who do less serious crimes, like shoplifting, and there is growing sense that jail is not the answer for many of these non-violent offenders anyway. So courts have been experimenting with alternatives. First it was drug court and mental health court, where a judge would suspend a criminal sentence in lieu of an offender’s agreement to enroll in a treatment program of some kind. But in recent years, special courts have been eclipsed by “diversion programs” that are more streamlined and offer intensive case management and referrals to a variety of support services, including mental health care, drug treatment, and housing.

There isn’t enough jail space to hold all those who are committing felonies, to say nothing of those who do less serious crimes, like shoplifting, and there is growing sense that jail is not the answer for many of these non-violent offenders anyway. So courts have been experimenting with alternatives. First it was drug court and mental health court, where a judge would suspend a criminal sentence in lieu of an offender’s agreement to enroll in a treatment program of some kind. But in recent years, special courts have been eclipsed by “diversion programs” that are more streamlined and offer intensive case management and referrals to a variety of support services, including mental health care, drug treatment, and housing.

The largest of these is the Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion program, or LEAD. LEAD is the brainchild of Lisa Daugaard of the Public Defender Association (PDA), a private group that once contracted with Seattle to provide legal representation for indigent clients but now focuses more on program delivery and advocacy. LEAD’s star has been rising in Seattle and around the country for the last decade. It’s been featured on respected news magazines like Frontline and praised in editorial and news columns across the country. In a 2019 opinion column, New York Times writer Nicolas Kristof said the program showed that Seattle had “figured out how to end the war on drugs” and last fall Daugaard was awarded a MacArthur “Genius” Grant of $500,000 and her program’s annual budget got a boost from $2.5 to $5 million from the Seattle city council, although that money is currently on hold while a skeptical Mayor Durkan weighs the evidence for the program.

The Seattle Municipal Court is busy, and whenever judges can refer an offender to one of these programs, they will. When they can’t for some reason, they are likely to offer the offender easy terms, suspending sentences in lieu of the offender agreeing to go for mental health counseling or outpatient drug treatment, and promising not to reoffend. But it often happens that offenders – especially repeat offenders – will skip out on the treatment and counseling and reoffend within days or even hours of being released. Often, when that happens, city prosecutors won’t increase the penalty and ask the court to impose a stiffer sentence or keep the offender in jail. Instead, they’ll ask for the same deal as before: time served and a promise to attend treatment. Naturally, the public defender approves this plan as well; it’s their job to get their client as light a sentence as possible.

Occasionally a judge will get fed up and try to stick their foot in the revolving door. That’s what this story is about.

(If you see a notated word, you can click on it to see the note.)

On December 10, 2018, the presiding judge (1) of Seattle’s municipal court, Ed McKenna, expressed his frustration at a probation deal that the prosecution and defense had agreed to for a prolific offender named Francisco Calderon. Calderon was not part of LEAD or any other diversion program, but he was a revolving door offender, and on that day he was before the judge on an assault charge, one of several misdemeanor offenses he’d committed in the last few year. The deal the prosecutor and Calderon’s defender wanted McKenna to approve in exchange for Calderon’s guilty plea was to let him out of jail with time served and a promise that he’d attend treatment programs.

But Judge McKenna was skeptical. Noting Calderon’s uncooperative demeanor,and his apparent unwillingess to change his behavior, McKenna decided to leave Calderon on ice pending a thorough review of Calderon’s long criminal history. Calderon and the attorneys were clearly displeased by this outcome, and when the next hearing rolled around, Calderon was even less cooperative. He had to be brought to the post-review hearing against his will – “I don’t give a crap!” he yelled from his cell when told he was due in court – and Judge McKenna, less convinced than ever of the efficacy of the agreed sentencing recommendation, handed him the maximum tern of 364 days in jail.

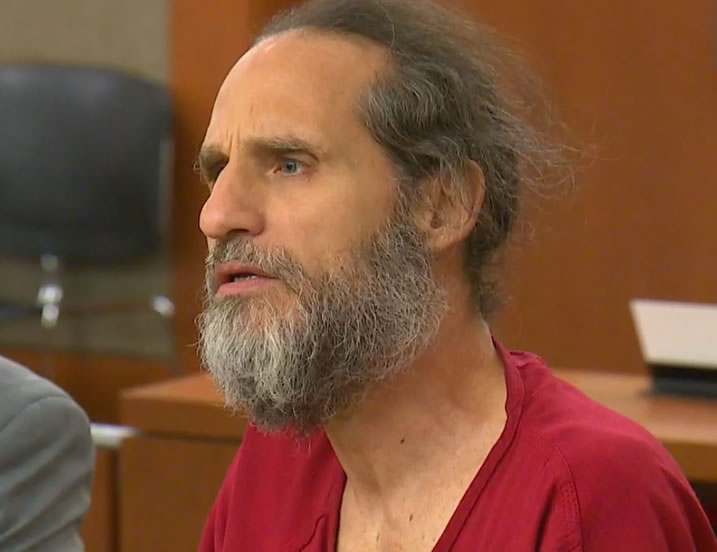

Francisco Calderon

My friend Jennifer Coats was in court that day and described what happened in a story she wrote for the Safe Seattle Facebook page on January 23:

Under police escort, a handcuffed defendant, Francisco Calderon, was brought into the courtroom. He was there under charges of assault on a stranger. Calderon had been picked up at 88th and Aurora on November 18, 2018.

Prosecuting attorney Kristina Georgieva asked the judge to dismiss the charges and let Calderon go, with two years of probation. After reviewing Calderon’s criminal history, Judge McKenna noted with dismay that Calderon had over 60 convictions, including felony assault, assault with a deadly weapon, and numerous other assaults. That’s not even all the arrests, he pointed out. And thirteen of those convictions had occurred since 2010.

In Calderon’s defense, Moore replied that Calderon had been in mental health and drug treatment for the past two years and was currently residing at the House of Mercy, a halfway house for offenders trying to reintegrate into society. He noted that Calderon was born in 1963 and said that was a long time to acquire all the charges. There was also a gap when Calderon didn’t have any convictions, he added, optimistically.

But the judge was unimpressed, noting that the no-convictions period was while Calderon was in prison. “The question I have,” said Judge McKenna, “is, at what point does the city decide to protect the public? Given someone’s history such as Mr. Calderon’s, isn’t it likely he’s going to commit another offense… and most likely a serious offense?

Jennifer Coats

The story on Judge McKenna’s comments and his decision to go so far above the prosecutor’s recommendation in sentencing Calderon made waves at city attorney Pete Holmes’ office, waves that were amplified when KOMO TV’s Matt Markovich ran his own piece on Calderon a week later. Holmes, an elected official, is in charge of prosecuting cases in municipal court. He’s the one who ultimately approves sentencing recommendations, including the one offered in Calderon’s case. Holmes took McKenna’s sentencing decision and the subsequent media coverage as a personal affront. So did Anita Khandelwal, head of the King County Department of Public Defense. DPD contracts with Seattle to provide defense attorneys for indigent clients like Mr. Calderon, and her team had worked together with Holmes’ on the Calderon probation deal that McKenna had criticized and set aside.

Eleven weeks later, on April 19, a Seattle business group hosted a panel discussion as part of series called City Makers on the city’s failing response to the issue of prolific criminals. Ed McKenna, who was one of the panelists, elaborated his position on “prolific offenders” like Calderon and why the City Attorney’s handling of them was a problem. “It’s really a prosecution-driven system,” McKenna told the audience:

The prosecutor makes a recommendation to the court. They gather the evidence. They look at the videos, they talk to the witnesses and they negotiate with the defense attorney and basically they say if your client accepts responsibility for, say, this theft, we will recommend X as a sentence. If your client insists on proceeding to trial however, we are going to ask for something different. In other words, more. So, in other words, reward a defendant for accepting responsibility for the actions that they’ve taken.

What we see now, however, is typically an avoidance of court oversight, so a prime example is just this past week I had a defendant that had been charged with two counts of theft. Two different cases, one from Macy’s the other from Target, downtown Seattle. The person had a serious history of drug offenses and thefts on their history. So it was apparent to everyone that the person had a drug problem when apprehended and one of those cases they had two grams of heroin in their pocket and admitted to stealing to support their habit. And the recommendation from the prosecutor was: Plead to one of those cases, dismiss the other and impose eight days in jail, which the person already served and close the case.

“Close the case” means there are no services. And I said, “Isn’t this exactly the type of offense that the community is complaining about? What incentive does the defendant have to not reenter that store and what services are we going to impose on this defendant to ensure that they get the treatment they need? So they don’t re-offend and then be back here next week.” And the response was, “Well, he’s serving eight days.”

The host asked: “So it really is literally zero effort to change behavior then?” And McKenna replied: “In many of those prolific offenders, there is not a significant effort.” More on the City Maker’s story here.

As presiding judge, McKenna might have thought he was free to speak his mind on such matters, free to criticize the City Attorney’s policies and free to opine on the state the court generally. What he didn’t know was that at the moment, Pete Holmes and Public Defender chief Anita Khandelwal, whose policies he’d questioned, were crafting a public indictment that would have deep implications for McKenna and for Seattle’s criminal justice system as a whole. On April 24, they delivered the letter to McKenna’s office and sent a copy to the Seattle Times. The Times published it the same day, so by the time McKenna read the charges against him, thousands of his fellow Seattleites had seen it too. The letter is below:

Holmes_Khandelwal_letterThe general charge against McKenna was that he had violated the state’s judicial ethics rules (the Canons) that are designed to assure an impartial judiciary. Specific charges included that:

- McKenna had claimed at the City Maker event that he was “forced” to accept the prosecutor’s sentencing recommendation 99% of the time.

- He had asked prosecutors to stop being lenient with offenders and to impose longer sentences so that he wouldn’t have to be the “bad guy” when he chose to go beyond them, as he did on the two recent cases covered by KOMO.

- He had invited reporters into his courtroom on specific days so they could witness a “premeditated display” of judicial toughness, which included having a defendant brought to court with a “drag order.”(2)

The letter concludes by asking McKenna to step down as presiding judge and to either “comport [himself] in a way that conforms with the Canons of Judicial Conduct” or to recuse himself from all criminal cases. And until McKenna refused to step down as presiding judge, the authors pledged that they and their staffs would boycott the regular bench-bar meetings he called.

Faced with this ultimatum, McKenna had three choices: He could ignore the letter, repudiate the charges, or acquiesce. Ignoring the letter would have amounted to an admission of guilt, as would acquiescing to the demand to step down as presiding judge. He chose to repudiate the charges.

In a brief response letter published next day in the Seattle Times, McKenna declined to step down as presiding judge. He said his accusers’ interpretation of his remarks at the City Maker event were incorrect and he denied the claim that he had invited members of the press or public to come to court to see a specific sentencing. He noted that the two individuals mentioned as witnesses denied it as well. With respect to the other allegations, including claim that McKenna had asked prosecutors for longer sentences, he said the claims were “too vague for a detailed reply,” but he left the door open for his critics to approach him privately with specific complaints.

The judge ended his response with a reference to the Rules of Professional Conduct for members of the state bar and directed Holmes and Khandelwal to “correct your errors.”

Response-McKenna

I will return to the Holmes-Khandelwal letter, but first we have to rewind the clock a month to consider Judge McKenna’s relationship to a person who can be considered a silent partner in this drama. Lisa Daugaard of LEAD, whom I introduced above.

Since at least the summer of 2018, Daugaard and McKenna had been carrying on a public quarrel over the city’s probation program. Daugaard has said that probation and jail are not lowering recidivism rates and that a greater share of the city’s budget should be given to diversion programs like hers. At a large city council hearing in October 2018, she advocated for money to be moved from the city’s probation budget into a handful start-up diversion programs for youth she was associated with. “The reason we supported the probation reduction plan,” she told me, “was that we are committed to data-driven policy and were familiar with the poor case for probation as a crime reduction strategy. There is no research-based case that municipal probation is effective for a large swath of the population; however, there is an extensive, rigorous research base that it is not [effective] or is even counterproductive.”

This kind of talk was worrying to Judge McKenna, who relies on jail and probation as sticks to be applied to those offenders who don’t respond to the carrot of diversion programs. And he’s been particularly skeptical of Daugaard and LEAD. Just days before the first Calderon hearing, he explained his views to a group of neighbors at a police advisory council meeting in north Seattle, as recorded in the meeting minutes:

Ed is concerned about the harm reduction and low barrier approaches to

drug addiction. He thinks they make it ok to keep committing crimes. And he believes that it is hard to address mental health needs when people are using drugs and alcohol. He thinks Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion (LEAD) is not effective regarding recidivism. One criticism he has of LEAD statistics is the conviction rate, which is based on 3 months, a time period too short, since many convictions take a lot longer than that.

Lisa Daugaard

That Daugaard had a bone to pick with McKenna is clear, and given Daugaard’s influence at the Municipal Court and in city politics generally, it’s no surprise to think she would use it. Though her method was less direct than McKenna’s, it was no less forceful. On March 23, 2019, two days after McKenna had delivered another one of his long sentences to a prolific offender, Daugaard sent an email to nine of her colleagues in the public defender community, listing several potential ethical violations by McKenna. She asked the recipients to look into her claims and, if they turned out to be “well-founded,” to file a complaint against McKenna with the state’s Commission on Judicial Conduct, the voter-established body used to investigate ethics complaints against all Washington judges below the federal the level:

Daugaard-Email-March-2019-basic_optNote that one of the recipients of the email is Anita Khandelwal, head of the Department of Public Defense. Given that Daugaard seemed to have the goods on McKenna, it’s noteworthy that she didn’t file a complaint herself. “I’d rather that it not be PDA [Daugaard’s Public Defender Association], as [Ed McKenna] is already going around town attacking me by name as a threat to public order, but there are those of you who would be expected to object to this.”

There are those of you who would be expected to object to McKenna’s behavior. Maybe the City Attorney could join.

That was a rather obvious cue.

As it turned out, City Attorney Pete Holmes did join the project, in a big way. Though he wasn’t one of the original email’s named recipients, Holmes did get a copy of it, as a public disclosure request to Holmes’ office later revealed. A month and a day after Daugaard sent her email, Holmes and Khandelwal published their broadside against McKenna.

The Holmes-Khandelwal missive differs on a couple points from the Daugaard email, but the thrust is the same, and the centerpiece of both is the claim that McKenna “invited” or “arranged for” Ms. Coats and Mr. Markovich to come to his courtroom to witness the “spectacle” (Daugaard called it a “publicity stunt”) of him sentencing uncooperative offenders to long terms. But note that while Holmes and Khandelwal did pick up on Daugaard’s cue about a complaint, they did not not follow her advice on how to make it. Or so it would seem. Daugaard had asked readers to “explore” her claims – some of which she only suspected were true – and if they determined them to be “well-founded” then she hoped they’d make a judicial ethics complaint. Meaning an official complaint to the Commission on Judicial Conduct.

Why didn’t they go to the CJC? Or did they?

The Commission on Judicial Conduct is composed of three judges, three attorneys, and six non-attorney citizens. On the Commission’s About page is a description of its mission:

The function of the Commission is to investigate and act on complaints of judicial misconduct or disability. All fifty states and the District of Columbia have judicial conduct agencies . Washington’s judicial conduct commission was constitutionally created when voters passed the amendment to Article IV, Section 31 of the Washington State Constitution in November 1980. For more information, see the governing provisions section of this website.

As seasoned attorneys, both Holmes and Khandelwal knew about the CJC’s function and its primacy in handling complaints against judges. Indeed, the same judicial canons they cite in their case against McKenna are the CJC’s version of the 10 Commandments. But just in case they weren’t aware of where to lodge their complaint against McKenna, Daugaard spelled it out for them in two places: in the subject line of her email (“Judicial conduct complaint about Ed McKenna”) and at the end, where she directs readers to explore her allegations and, if well founded, to make a “judicial ethics complaint.” Was Daugaard suggesting that recipients file a complaint any old place? Like in the newspaper, maybe? No.

So why didn’t Holmes and Khandelwal go to the CJC? Well, we don’t know that they didn’t. The CJC enjoins complainants from disclosing the fact that they filed a complaint or discussing the details, but it doesn’t preclude them from bringing the same complaint concurrently in the public forum. So Holmes and Khandelwal, and also Daugaard, and any of the other people on Daugaard’s Cc list, may also have filed complaints with the CJC. And unless those complaints were upheld, the rest of us would be none the wiser.

Would there have been any disadvantage to them in bringing the complaint against McKenna both publicly and privately? No, not really. They risked nothing worse than a scolding from their fellow jurists for publishing their letter, which they duly received in an op-ed from the other judges (see below). But that scolding came several days after they made a splash in the Times, and the response was muted.

One McKenna supporter said confidentially that a formal complaint to the CJC would have required Holmes and Khandelwal to perjure themselves, and that’s what kept them away. But I disagree. Since their most solid accusation against the judge was little better than conjecture it could not be considered an outright lie. Ergo: no perjury. Evidence suggests that McKenna invited people to court to hear a sentencing, they wrote. Not “evidence proves.

Holmes and Khandewal would have painted themselves into a corner if they’d gone to the CJC exclusively, because if they lost in that venue it would have been game over. And even if they’d prevailed, it’s certain that the CJC’s sanction on McKenna (3) would not have been as harsh as the one they called for in their letter. I believe they did file a complaint against McKenna with the CJC, but since dismissed complaints are confidential, no one will ever know.

The Scolding

A week after the Seattle Times printed the Holmes-Khandelwal letter, they printed an op-ed signed by seven judges criticizing Holmes and Khandelwal (and, indirectly, the Times itself) for not following Washington’s constitutional procedure for disciplining judges:

As judges, we write to express concern that this process for addressing complaints against Seattle Municipal Court Judge Ed McKenna has been bypassed, the authors wrote, in favor of public complaints released to the media by Seattle City Attorney Pete Holmes and Anita Khandelwal, director of King County Department of Public Defense. [ . . . ] There are good reasons why complaints against judges are not made public until the Commission on Judicial Conduct finds probable cause for the validity of the complaint. If complaints were made public, it would have a chilling effect on judges if they had to respond to every unhappy litigant that publicly made unfounded allegations. Such an environment would provide an incentive to tip the scales of justice with unfounded public complaints to influence the judge’s discretion or to retaliate for judicial decisions as a way to control the ultimate outcome of future cases.

The Case on its Merits

Let’s turn now to the specific charges against McKenna. I will identify each charge by the party or parties who made it.

Charge 1 ~ Judge McKenna met with city council candidate Ari Hoffman “in the middle of a court session” casting doubt on his impartiality (Daugaard)

It’s true that Hoffman met with Judge McKenna in the judge’s chambers. Hoffman showed up in McKenna’s courtroom on March 13, 2019, which happened to be the day of the James Lamping sentencing. He was not there at the request of McKenna but at the invitation of Jennifer Coats, who had been following court proceedings for several months by then and thought Hoffman, as a council candidate running on a platform of public safety, might find them interesting. McKenna recognized Coats in the courtroom and called her and Hoffman over to chat between sessions. I asked all three of them, Hoffman, Coats, and McKenna, if they’d discussed any of the cases in progress that day, and they each told me no. After I read Lisa Daugaard’s March 23 email, I asked her if she knew what McKenna and Hoffman had talked about in court that day, and she told me she didn’t. Did she think it was inappropriate for a judge to talk with candidates at the courthouse? I wondered:

That would not be per se improper, no. The crux is always that a judge must both (a) be actually open-minded about the resolution of a case on its own merits and without reference to his or her own political advocacy objectives or making a point or sending a message via a case before the judge; and (b) that this impartiality and neutrality be perceived as well as real (appearance of fairness issues). Meeting a particular candidate who had a public posture about the way cases were being approached by the prosecutor in the courtroom could send a message contrary to that required neutrality and impartiality. Whether this sort of conduct would in fact be improper would be a fact-driven question.

So did Ed McKenna send a message by meeting with Hoffman privately? That’s a stretch. Hoffman wasn’t a celebrity, and McKenna had never met him before Jennifer Coats introduced the two men to each other. What was the judge supposed to do? Tell Hoffman to get out of his courtroom? Any civilian who’s visited Seattle Municipal Court know that’s not how it works. Judges – and particularly the presiding judge – are eager to chat with visitors and educate them about the court. I saw this for myself when I showed up in another judge’s court as an observer. As soon as the session ended, both the judge and the prosecutor approached me and asked if they could answer questions. Even after I told them I write for the Safe Seattle Facebook page, with which they were both familiar.

Ari Hoffman

Daugaard had a chance to ask Hoffman about his conversation with McKenna when she met him seven weeks later, on May 14, to discuss the LEAD program, something she did with all the leading council candidates. By that time, Hoffman had already gotten a copy of Daugaard’s March 23 email, and he decided to ask her about it. He told me what happened:

I waited till the end of the LEAD briefing and said, “This was such a nice meeting. In the future if you have a problem with me or hear something about me, call me. Don’t write emails about me.” She said, ‘What are you talking about?’ I confronted her on the email two more times and she denied knowing what I was talking about. Then I pulled out the hard copy and showed her what she’d written.

(Daugaard disputes Hoffman’s account. “As soon as Ari asked me about the email, I discussed it with him,” she told me.)

I asked Hoffman, “Did she ever ask you what you and McKenna talked about in court that day?” –No, he said.

Charge: DISMISSED

Charge 2 ~ Judge McKenna was doing political organizing. (Daugaard)

Daugaard said in her email: “I suspect there may be judicial ethics issues about EM’s political organizing work in which he goes around town saying untrue things about policy and practice, misrepresenting the efficacy of court programs, and generally advocating for a general approach to crime that might cause reasonable people to question his impartiality in individual cases.” [emphasis added] Her interpretation is highly subjective, of course, but beyond that, absent some evidence that McKenna had spoken out about a specific case in progress this complaint would not merit consideration by the CJC. Again, the key idea here is that a judge not speak out about an individual case in progress, and especially while court is in session. Canon 2A (Rule 2.3) states:

- A judge shall not, in the performance of judicial duties, by words or conduct manifest bias or prejudice, or engage in harassment, and shall not permit court staff, court officials, or others subject to the judge’s direction and control to do so.

- A judge shall require lawyers in proceedings before the court to refrain from manifesting bias or prejudice, or engaging in harassment, against parties, witnesses, lawyers, or others. [Emphasis added.]

Did Judge McKenna say something to the media, to private citizens, or to community groups that would cause a reasonable person to question his impartiality in a particular case pending in his courtroom? Daugaard’s email doesn’t speak to that.

On a personal level, Daugaard’s position is rather disingenuous. She faults McKenna for political organizing, but she’s no slouch at politicking. In October of 2018, Daugaard appeared at city hall at the head of a large contingent of activists from her “Budget for Justice” advocacy group. They were asking the council to cut $4.2 million from the jail and probation budget over the next biennium and give it to youth- and minority-centered “restorative justice” programs with names like: Community Passageways, Creative Justice, and Got Green. A program run by Daugaard’s own Public Defender Association was on the wish list, too, along with one run by the Washington Defender Association, several of whose members Daugaard had included as Cc’s on her March 23 email.

Naturally, Ed McKenna saw Daugaard’s request to slash funding from things he liked and give it to ones that she liked as a threat. She had also publicly criticized his approach as being costly and ineffective. As presiding judge, why wouldn’t he be entitled to criticize hers in turn? He did do that, in fact. In remarks to the North Precinct Advisory Committee some two weeks later, he said

The SMC’s probation program is under fire by citizen group Budget For

Justice. BFJ is advocating dis-investment in the local criminal justice

system, and in particular cutting the probation program’s budget by 90%

over 3 years and diverting the money to fund juvenile offender services.

Lisa Daugaard spearheads this effort (she also co-chairs the Community

Police Commission).

In making those criticisms McKenna said he was speaking for himself only, and not the Seattle Municipal Court.

Charge: DISMISSED

Charge 3 ~ Judge McKenna made public and private statements that call his impartiality into question. (Holmes-Khandelwal)

In their April 24 letter, Holmes and Khandelwal say:

Canon of Judicial Conduct 1 provides that a judge shall act “at all times in a manner that promotes public confidence in the independence, integrity, and impartiality of the judiciary.” You have repeatedly made statements that undermine public confidence in the impartiality of the judiciary. On April 19, 2019, you spoke at the Downtown Seattle Association’s City Maker breakfast. There, you suggested that you felt bound to follow prosecutors’ recommendations 99 percent of the time. This suggests the very opposite of impartiality – and that you disregard the advocacy of defense counsel.

Here’s what McKenna actually said at the City Maker event (bold text added):

We had that when I was a prosecutor we looked at prolific offenders. We called it the ‘high impact offender project’ and persons were on that list and those persons were targeted for additional effort. Judges typically 99 percent of the time will follow the recommendation of the prosecutor. And we rely on the prosecutor because we expect that they are going to make a reasonable recommendation based on the defendant’s criminal history of the nature of the offense and the strengths and weaknesses of their case. And so we rarely exceed a prosecutor’s recommendation in those cases. And so really it’s pretty much a prosecution-driven program.

Ms. Khandelwal later clarified in an email to KUOW’s Sydney Brownstone that while McKenna hadn’t said he felt bound to follow prosecutors’ sentencing recommendations, there was a clear implication there. Perhaps, but in any case, McKenna is just stating a fact, he and his fellow judges all rely on prosecutors for sentencing guidelines. Here’s how he explained it to me in an email:

The plea form itself only has a space for the prosecutor’s recommendation, not the defense. That’s so the defendant will know what the prosecutor will argue to the judge. The form also clearly says that the judge doesn’t have to follow the recommendation and can impose any sentence up to the maximum.

When judges sentence defendants, we don’t know much about the case, other than what we have access to. That can be because police officers only had time to write a short report, because prosecutors didn’t want to share too much information about their case to prevent the defense from learning of its weaknesses, because the case didn’t proceed to trial, or several other reasons.

In most cases, we only see the police report and criminal history. The prosecutor knows the strengths and weakness of their cases, meaning they evaluate witness credibility and testimony, defenses to the charge, and other information available to them. Judges assume, in most cases, that prosecutors have conducted such investigations and their recommendations are reasonable based on the strength of their cases. That’s one main reason that judges usually follow the recommendations. While judges will of course hear the defense arguments regarding sentencing, virtually every plea in our court is an “agreed” recommendation, as it was in the Calderon case. Agreed recommendations have become so prevalent that one prosecutor, when questioned, actually told me that she thought all pleas actually had to be “agreed recommendations.”

I need to clarify the point about the plea form. Judges always ask the defense for their sentence recommendation. Likewise, we always provide the defendant an opportunity to speak at sentencing. The defense recommendation simply isn’t in the plea form, unless they squeeze it in somewhere. Once the plea is accepted, the prosecutor is bound to their recommendation. Basically, knowing what the prosecutor wants in advance of the plea provides the defendant an opportunity to weigh potential consequences of the risk if they go to trial.

Context is important here. McKenna made his comments about accepting prosecutors’ recommendations by way of arguing that prosecutors have been acting too much like defense attorneys. One doesn’t have to accept that hypothesis, but it is at least reasonable, and it fits with the rest of McKenna’s argument and with many media stories and Scott Lindsay’s “System Failure” report, which was the subject of the City Maker panel. Holmes and Khandelwal, by contrast, are ignoring McKenna’s argument about too-soft prosecutors and suggesting that McKenna is relying too much on their judgment. It’s as if they hadn’t heard anything else he said.

They further complain that McKenna has had “numerous conversations” with Holmes and his prosecutors in which he criticized the City’s sentencing recommendations and requested longer sentences so that he could use his discretion to impose a longer sentence between the two without looking like “the bad guy.” But again, given McKenna’s premise that agreed sentencing recommendations are too light, asking prosecutors to be tougher seems reasonable. It does not seem prejudicial to the accused in general or to any accused in particular. We take for granted that Holmes and Khandelwal did not agree with McKenna that Holmes’ prosecutors were being too soft, but why didn’t they challenge McKenna’s argument on the merits instead of charging him with bias?

They claim he had another option. “As a judge,” they wrote, “you have the authority to impose any lawful sentence once a defendant is convicted and are not required to follow the City’s sentencing recommendations.” Which is true, and yet when he tried to use that authority to sentence defendants Calderon and Lamping to a longer sentence, they and Lisa Daugaard attacked him for it, accusing him of playing to the news cameras.

Charge: NOT PROVEN

Charge 4 ~ Judge McKenna invited KOMO reporter Matt Markovich to attend court on certain days so he could see McKenna making examples of repeat offenders, denying defendants their 6th Amendment right to allocution. (Daugaard, Holmes-Khandelwal)

This would be the most damning charge of all if it were true. But it’s not true. And there is no evidence that either Daugaard, Holmes, or Khandelwal made any effort to ascertain that it was. KOMO reporter Matt Markovich made two appearances in Judge McKenna’s courtroom, and on neither one of them was he invited by Judge McKenna so he could he witness a “publicity stunt.” I asked both McKenna and Markovich at least twice: Did you arrange with for KOMO to be there on a certain day to witness a certain sentencing? They both said no.

But wasn’t Markovich’s appearance in the courtroom suspicious? How did he know that this would be a good story? Because Jennifer Coats had told him. Coats had taken McKenna up on a general invitation he’d made to the audience at the November 2018 NPAC community to come see how the court worked. After making a few visits, she began working on the Calderon story for Safe Seattle, and at the same time she told Markovich, whom we both knew, that she thought it would also be a good piece for KOMO. After talking with Coats about Calderon case, checking the court calendar, and securing permission to film in court, Markovich showed up.

When the Holmes-Khandelwal letter appeared in the Seattle Times, on April 24, I got back to Coats right away, because she was mentioned in the letter, and so was Safe Seattle. (The authors had confused Safe Seattle with a group called Speak Out Seattle, suggesting that they couldn’t even get basic facts straight.) I said, “They’re saying McKenna arranged with Markovich to be in court. Do you know anything about that?” Coats said “No. That didn’t happen.”

“Are you sure? It does look kind of suspicious, Markovich being there at the time of those two dramatic hearings.”

Coats reminded me that McKenna sees those prolific offenders day in and day out. There are plenty of Francisco Calderons going through the court’s revolving door. Go there any day court is in session, she said, and you’ll see one.

Charge: NOT PROVEN

The Gun That Wouldn’t Smoke

In the weeks and months following the publication of their letter in the Seattle Times, Holmes and Khandelwal’s evidence on the Markovich fell apart. In their letter, the pair had mistakenly identified Jennifer Coats as being a member a neighborhood group called Speak Out Seattle. Elisabeth James, a leader of Speak Out Seattle didn’t like that, so she confronted Holmes at a public event and asked him how he knew McKenna had invited Markovich into his courtroom on a certain day. Holmes told James he had an email that implicated McKenna on that, and she could see it if she wanted. But when James followed up with Holmes’ office, the email they gave her – the one that was supposed to constitute evidence against McKenna – was the March 23 email from Lisa Daugaard! (4) When I learned of that conversation, I asked Markovich if there was some other email Holmes might have had implicating him:

Hi, David. No email like that exists at all. I have an email exchange with Gary Ireland [public information officer for the Seattle Municipal Court] asking for permission to put a camera in the courtroom before the Calderon sentencing in January [0f 2019]. That’s the only communication I had with the court prior to filming in Judge McKenna’s court room.

I spoke with Lisa Daugaard several months ago about this and challenged her on it. The only email I exchange I had with Judge McKenna’s courtroom before the hearing was to ask permission for a camera in the courtroom – it’s practice we in TV News do all the time and it’s the judge’s decision to grant it or not.

I did say after the ruling to Lisa in a phone call when I was putting my story together that I thought Judge McKenna was sending a message with the sentencing – but that was after it happened and it was only my opinion. Lisa declined to do an interview with me.

Leaving no stone unturned, I asked Daugaard, via email, what evidence she for her claim about Markovich and McKenna. She didn’t produce any, but she did send her recollections of a discussion she’d had with Markovich on the subject after the Holmes-Khandelwal story broke. This is taken from notes she made at the time:

On Wednesday May 22, after a City Council briefing on the Prolific Offenders report, Matt Markovich of KOMO approached me to discuss the events surrounding the Calderon sentencing, my email to the City Attorney’s Office and the King County Department of Public Defense, their letter, and Judge McKenna’s response. Matt indicated he had seen my second [March 23rd] email to CAO/DPD. He said “I remember making [a] statement [about McKenna playing to the cameras] to you.” [ . . . ] Without me asking, he offered to explain how it came about that he was in the courtroom for the Calderon hearing. He said “Judge McKenna invited Jennifer Coats to observe court hearings, and she invited me.” Mr. Markovich used the word “invited.”

The note I included in my second [March 23rd] email to CAO and DPD, about Judge McKenna reportedly stepping down from the bench to meet with Council candidate Ari Hoffman, was based on a conversation on March 22 with an assistant City Attorney, after a meeting on other subjects, in which that Asst City Atty reported that that had occurred. My impression was that CAO attorneys had witnessed this firsthand. Ari Hoffman, on May 14, at a meeting at PDA, having seen my email in response to a public records request, said it didn’t happen that way — they didn’t meet in court.

Hi Andrew,I’d be happy to talk with you, though I don’t know that it will add to the story. The “inviting reporters” point (those were not the words I used–I said “arranged with”) wasn’t the crux of what I was getting at in my communication with the City Attorney and DPD, but rather, the use of an individual case to send a message about a broader policy position with which was judge was affiliated. My obviously informal email wasn’t meant to be a source document, but just to initiate a discussion about whether the City Attorney or DPD had additional information and whether they were aware of the various episodes I alluded to.In a different, earlier, set of notes I sent to the same offices, on January 23, I recounted, very close in time to when it was made, the comment KOMO’s Matt Markovich made to me when he called about the Francisco Calderon case. He said he knew the judge “was clearly playing to the camera.” This is either a verbatim quote or very close — it was a memorable comment and I made the note immediately after. I believe he also said Judge McKenna had called him (Markovich), which is the only specific fact I shared in the March 23 email you sent an excerpt from.After a gap of four months, that is the best recollection I have of exactly what Mr. Markovich recounted about Calderon. I later surmised that the “call” may have been “arranging,” because reporters again showed up in Judge McKenna’s court to witness the sentencing in what would otherwise seem like a fairly routine case, that of Mr. Lamping, where Judge McKenna announced that was employing a creative new sentencing technique for a person suffering from substance use disorder. It seemed unlikely to me that the TV crew would just happen to be in court for this particular, fairly routine case. That, together with what Mr. Markovich had told me in January, led me to say that it appeared that the judge had advance awareness of the reporters’ presence–but again, that wasn’t the central point I raised with DPD and the City Attorney. The point was whether the individuals’ cases were being used to advance the judge’s previously and publicly announced policy agenda, rather than being adjudicated by a neutral and impartial magistrate who was truly open to the case the defendants and their counsel made during “allocution,” the 6th Amendment right of a defendant to attempt to persuade the judge at sentencing.Of course, both of the departments I wrote to had had lawyers in the courtroom to observe, so I didn’t expect to be the primary source of information about this set of events. The only additional information I had besides what would have been evident to anyone in the courtroom was the call from Mr. Markovitch on January 23, where he characterized Judge McKenna’s demeanor and apparent motivation as I have described above, and, I believe, said the judge had called him.Let me know if you need anything more.Lisa Daugaard

On December 13, I sent Pete Holmes and Anita Khandelwal, separately, via email and post, a list of 10 questions regarding the McKenna affair. I explained that I was writing this article and that I was trying to understand how they arrived at the decision to publish an open letter to McKenna rather than following the constitutionally created process of the Commission on Judicial Conduct. I also wanted to know whether they’d spoken with Lisa Daugaard about her March 23 email, which they had both gotten, and what steps they had taken independently to ascertain that Daugaard’s claim about about McKenna and Markovich were correct. Here’s a copy of the version I sent to Holmes:

Pete-Holmes-Letter_redacted2I got no answer from either of them, but when I asked Daugaard whether they had spoken with her about their letter or had followed up with her for details about the Markovich allegation, she said no. Matt Markovich told me they hadn’t spoken with him about it either. As far as we know, Anita Khandelwal never approached McKenna about it but Judge McKenna told me that he and Holmes did speak about it briefly in person and that at that time he told Holmes he had not invited the media to his courtroom:

Shortly after the Calderon sentencing, Mr. Holmes came to my office to express his displeasure at my sentencing. At that time he also told me that he was going to join with the defenders in making a motion to reconsider my sentence. Recognizing that as ex parte contact, a clear ethics violation in itself, I told him I would have to recuse myself from hearing his motion. Apparently, he thought twice about his motion because it didn’t happen. In that same conversation however, he also complained about the media coverage. I informed him that I had not invited the media and explained they had been invited by a member of the public. Despite my telling him directly that I had not invited the media, he made public allegations anyway.

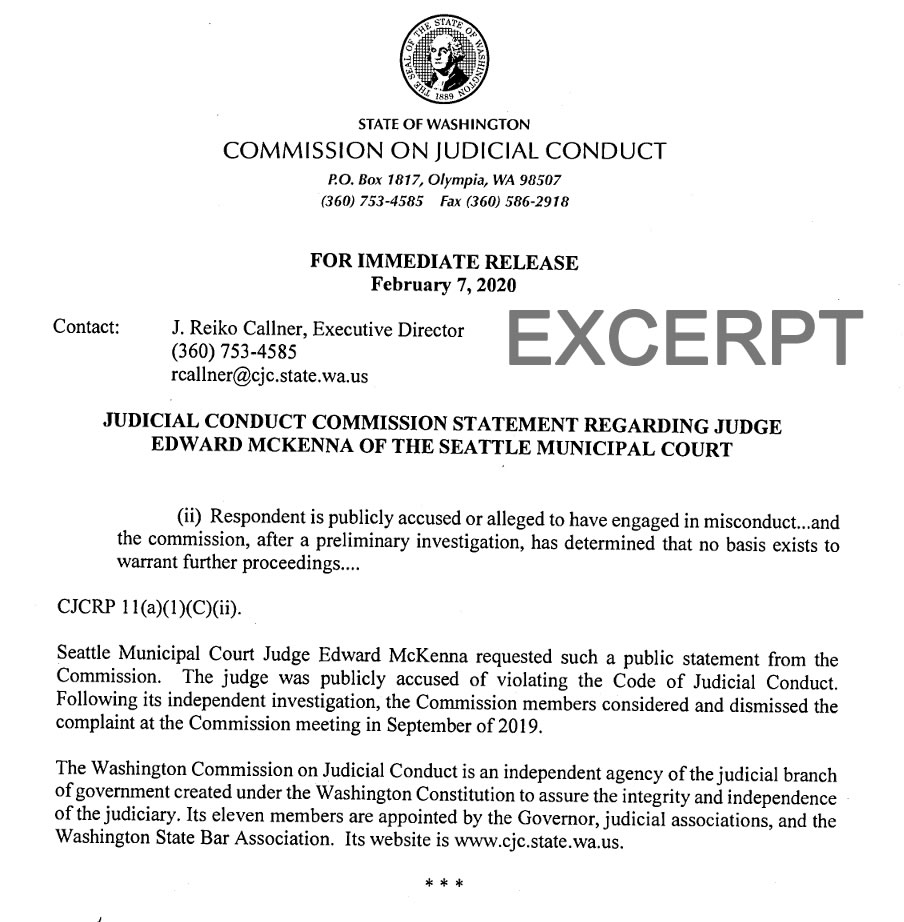

Fallout

Within days of the Holmes-Khandelwal letter, Judge McKenna decided to try and exonerate himself by filing a complaint against himself with the CJC based on the same charges. And that complaint was duly dismissed, according to a KOMO story, after a months-long investigation. On February 7, 2020, the CJC issued a press release stating that after a preliminary investigation they had found McKenna to have committed no misconduct. Below is an excerpt of the CJC press release. Click to see the full document:

On first flush, it would seem that the Holmes-Khandelwal gambit failed. Judge McKenna didn’t accept the charges, didn’t step down as presiding judge, and didn’t recuse himself from criminal cases before the court, as the pair had demanded he do. Meanwhile, seven respected judges from across the sate published their own letter which, though it didn’t exonerate McKenna outright, thrashed Holmes and Khandelwal for not following the process.

But all that was cold comfort, because in the meantime, Holmes and Khandelwal have applied their own sanctions, just as they threatened: “As long as you remain presiding judge and convene bench/bar meetings,” they declared, “neither the City Attorney’s Office nor the Department of Public Defense will attend.” And they’ve been as good as their word. From April 2019 till now, Holmes’ and Khandelwal’s staff have refused to attend these monthly meetings.

McKenna described how the Holmes-Khandelwal boycott was affecting his court:

It doesn’t impact the operation of the court but it does impact the rights of defendants and procedures for attorneys. For instance, at a recent bench bar meeting, we discussed the problem of attorneys and defendants appearing late for the master (trial) calendar and ways address that behavior. In the absence of the prosecutor and public defender, (reps from the private bar still come) we decided to note an FTA [failure to appear], meaning a defendant’s right to a speedy trial starts anew. That’s a significant impact to defendants rights. Also, we ordered that attorneys would need to immediately report to their assigned court for trial without delay, meaning late attorneys could potentially face sanctions. The boycott is really silly in that it it doesn’t impact the court, but rather it punishes attorneys and defendants by forfeiting their right to provide input to the court. We still hold the meetings, though less frequently.

McKenna added that the Department of Public Defense, Khandelwal’s office, is contractually obligated to come to the meetings (5) but that Khandelwal had continued boycotting even after McKenna had pointed that out to her.

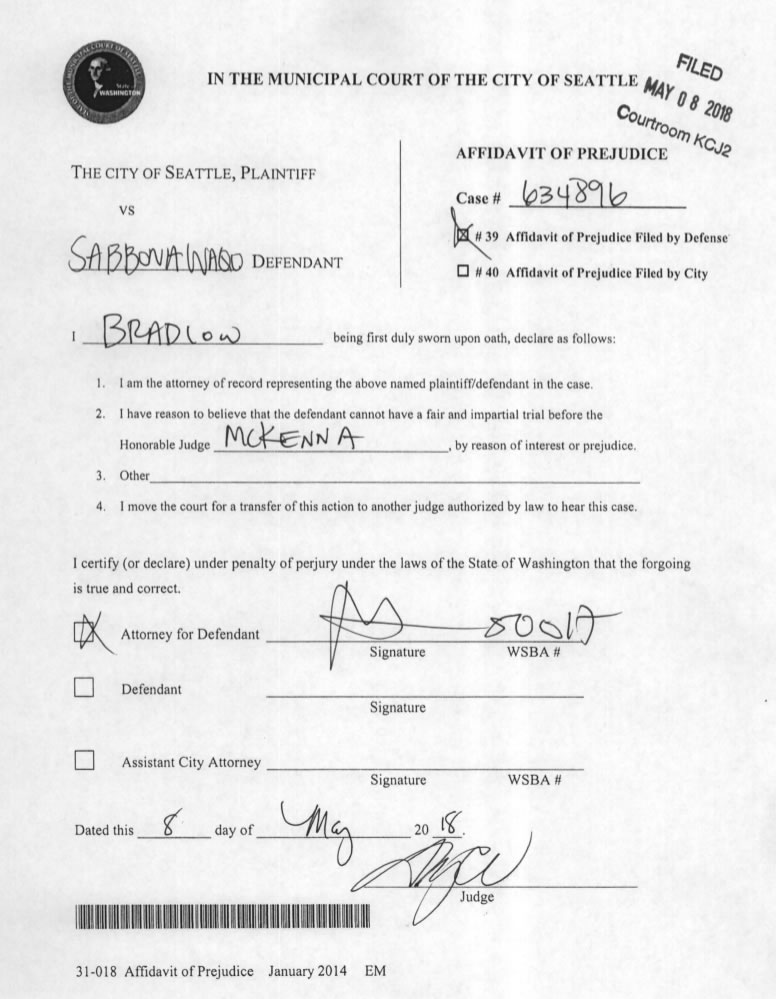

Meanwhile, Khandelwal’s attorneys have been reflexively filing affidavits of prejudice against Judge McKenna in all indigent cases assigned to his court. Two weeks after Holmes and Khandelwal published their letter, a court insider contacted me with a tip:

Both the Seattle City Attorney’s Office and Department of Public Defense (DPD) are submitting affidavits to get cases moved out of Judge McKenna’s court. An affidavit for a change of judge can be submitted once for each case, and whenever a case is assigned to Judge McKenna, some attorneys are automatically submitting affidavits of prejudice. That direction is likely coming from higher up. What I’m telling you can be checked by referencing the affidavits, which are a matter of public record.

The goal is to have zero cases heard in McKenna’s courtroom, and this is already impacting his calendar. The affidavits are being filed in retaliation against McKenna, because he actually sentences people for crimes committed, and apparently his enemies at the offices mentioned think this is a bad thing and want to force his resignation.

I looked into it, as the reader suggested, and discovered that there had been a marked increase in affidavits of prejudice filed against McKenna. Data I got in response to a public disclosure request shows that affidavit filings against McKenna from Khandelwal’s lawyers more in the six months after the Holmes-Khandelwal letter compared to six months previous! From late October 2018 to late April 2019 Khandelwah’s lawyers filed 116 affidavits. Holmes and Khandelwal published their letter on April 24, 2019, and in the next six months, 311 affidavits were filed. Here’s a list of them in an MS Excel file.

Do affidavits of prejudice matter? They can. Consider this one, for example:

It was filed on May 8, 2018 by public defender Rebecca Bradlow. Because of this affidavit, Judge McKenna was removed from the case of a young, gang-affiliated man named Sabbona Waqo, who was in court on his third charge of gun possession. Since Waqo had violated his previous probation conditions by carrying a gun, he should’ve gone straight to jail, but the defense and prosecution had other ideas. They decided to offer Waqo a plea deal by which he could skip jail and have the charge dropped altogether. All he had to do was promise not to commit any more crimes and to attend an eight-month restorative justice program called Community Passageways, which happens to be one of the programs Lisa Daugaard was calling for the city to fund in 2018 with money that had been allocated for the city’s probation office (see above).

Sabbona Waqo

I later spoke with the director of Community Passageways, Dominique Davis, and he told me that after showing up to the program a couple times, Waqo dropped out and didn’t return. But on July 18, 2019, Mr. Waqo, his new public defender, Elaine Saly, and city prosecutor Jenna Robert all signed off on a document saying Waqo had “demonstrated a connection” to Community Passageways, and the gun charge was dropped. Less than six months later, Waqo allegedly shot another young man to death in Pioneer Square. I asked Ms. Saly and Ms. Robert why they had just checked the box saying Waqo had attended the Community Passageways program when he clearly hadn’t. They did not respond.

Would Judge McKenna have been tougher on Sabbona Waqo? Would he have insisted that the prosecution and defense do more to verify that Waqo had attended the Community Passageways program and demonstrate to the court that he was reformed? His history suggests that he would have, but we’ll never know now, because Anita Khandelwal’s public defender had him removed from the case.

An affidavit of prejudice mimics the guilt-by-accusation strategy that Pete Holmes and Anita Khandelwal used in their public indictment of Judge McKenna. A lawyer who files one doesn’t have to say why they think the judge is prejudiced, just that he is. And while there is a limit of one affidavit per case, there is no limit to the number that attorneys can file overall. That makes the affidavit prerogative subject to abuse, particularly where several defense attorneys are working for one boss, like Anita Khandelwal, and that person has a vendetta against a particular judge.

Prelude to an Investigation

In mid-April 2019, long before I knew about Lisa Daugaard’s email, I proposed a meeting between Daugaard and Judge McKenna in the belief that they could reconcile their differences or at least agree to continue their public disagreement in milder tones. Daugaard agreed to meet, but McKenna declined, suggesting that I was naive for trusting Daugaard. So I met with him privately, and when I did, I brought a list of concerns Daugaard had asked me to question him about. It was similar list of criticisms that was in her email. The main charge was that McKenna was deciding sentences in advance of allocution, as evidenced by the Markovich broadcasts. In our meeting, McKenna assured me that wasn’t doing that, and he questioned whether Daugaard didn’t have a political motive for saying that.

When the Holmes-Khandewal letter came out, I was astonished to see how closely it resembled the list of grievances Daugaard had asked me to bring to my meeting with McKenna. I got back to her immediately and asked, Did you help them write that letter? No, she replied. But she didn’t need to. Her criticisms of McKenna were widely held at both the city attorney’s office and at the Department of Public Defense and elsewhere. I accepted that answer at the time. It wasn’t until Ari Hoffman shared Daugaard’s email with me months later that I decided the affair needed more looking into.

J’accuse!

(Non. Tu t’accuse!)

In reviewing the McKenna case, I believe that his accusers acted shabbily, but I don’t feel they share equal blame. Lisa Daugaard was within her rights to criticize Judge McKenna’s public statements about agreed sentencing recommendations and about her programs. Moreover, given that she believed that her charges against the judge were likely true, she was justified in asking other people to look into them further and to file a complaint with the Commission on Judicial Conduct – should her allegations turn out to be well founded. While her explanation for why she couldn’t pursue the matter herself strikes me as flimsy, it’s still plausible.

Did Daugaard go beyond that? Did she tell Holmes and Khandelwal to bypass the CJC? Did she help them write the letter they published in the Seattle Times? We can make inferences, but we don’t know, and in the absence of proof, we have to give Daugaard the benefit of the doubt.

Pete Holmes and Anita Khandelwal are the real bad actors here, and their wrong lies not merely in that they skipped the CJC but the mean-spirited way in which they did it. Prejudice and partiality are the worst possible accusations they could have laid against McKenna and they knew it. Given that they were going to take their case public, shouldn’t they have built a stronger foundation for it? Note the terminology that they use: Your invitation to Ms. Coats and apparent invitation to Mr. Markovich suggests you decided the outcome in Mr. Calderon’s matter before sentencing. In the accusers’ letter, the word “suggests” is used in this sense no fewer than three times. “Appears” or “apparent” also turns up three times. On the main allegation, why did they need to guess about McKenna and Markovich, when they could have checked with any one of the players (Coats, Markovich, or McKenna himself) to find out whether there had been an actual invitation? In the three months between Markovich’s first KOMO broadcast and their letter, they could have reached out to the principals at any time, and yet they failed to do so. Why?

Holmes and Khandelwal hurt Judge McKenna’s reputation with their letter, and even after the CJC exonerated him, and even as the corroborating individuals they cite in their letter have stepped forward to vindicate McKenna, neither of them have stepped up to apologize. Meanwhile, they’re still boycotting the judges bench-bar meetings, and Khandelwal’s public defenders are still barraging McKenna with affidavits of prejudice, all to the detriment of the defendants and the citizens.

Holmes and Khandelwal hurt Judge McKenna’s reputation with their letter, and even after the CJC exonerated him, and even as the corroborating individuals they cite in their letter have stepped forward to vindicate McKenna, neither of them have stepped up to apologize. Meanwhile, they’re still boycotting the judges bench-bar meetings, and Khandelwal’s public defenders are still barraging McKenna with affidavits of prejudice, all to the detriment of the defendants and the citizens.

A Second Trial

Holmes and Khandelwal can and should be sanctioned for their behavior. As Judge McKenna pointed out in his rebuttal letter, the Washington courts have rules of professional conduct for lawyers, and these rules are enforced by the Washington State Bar Association. Rule 8.2(a) states:

A lawyer shall not make a statement that the lawyer knows to be false or with reckless disregard as to its truth or falsity concerning the qualifications, integrity, or record of a judge, adjudicatory officer or public legal officer, or of a candidate for election or appointment to judicial or legal office. [Emphasis added.]

Rule 8.3(b) speaks to Holmes’ and Khandelwal’s failure to report their alleged concerns about Judge McKenna’s behavior to the proper authority (that is, the CJC):

(b) A lawyer who knows that a judge has committed a violation of applicable rules of judicial conduct that raises a substantial question as to the judge’s fitness for office should inform the appropriate authority. [Emphasis added.]

We don’t know whether Holmes and Khandelwal took their complaint to the CJC, but they can be compelled to disclose whether they did by the state bar association. If it is found that they did not file a complaint against McKenna, even while claiming that they had knowledge of him violating “applicable rules” (that is, the judicial canons), they should be sanctioned. Their ongoing boycott of the court’s monthly bench-bar meetings should be investigated by the state bar association and by the City of Seattle’s contract administrator. The boycott is a breach of both the contract and a breach of the parties’ ethical duties to protect the interests of their respective clients.

Finally, Khandelwal’s barraging of McKenna with affidavits of prejudice should be examined as a possible abuse of her discretion. Court rules should be put in place that trigger a review whenever there is a pattern of affidavits being filed on a single judge.

Clearly there’s a lot that needs looking into here. To borrow a line from Ms. Daugaard: Can someone explore these charges and, if well-founded, make a complaint?

–David Preston

Did you appreciate this article? Do you support honest journalism? Then please …

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank the following:

Almighty God, who created man and gave him a conscience.

Ari Hoffman, for his courage and patience.

Lisa Daugaard, for her relentless cooperation and her belief in a better world, by hook or by crook.

Jennifer Coats, for striking the spark that lit the blaze that illuminated the city.

E.J. for legal research.

Excellent article and very thorough. Thank you for this public service.

What is the motivation of Pete Holmes and crew putting these repeat offenders back on the street endangering the lives of the general public? Why do they want the streets of Seattle to be unsafe and scare the public away from the dwindling retail core? It defies logic.

We, we are with you. What do you need?