June 3, 2018 ~ Everyone’s talking about the Head Tax, about how much money it would raise, about how the money will be spent (or misspent), about how it might affect business… Almost no one’s talking about who it was that designed this tax in the first place.

The committee that developed the tax ordinance was called the “Progressive Revenue Task Force.” It was constituted by the City Council and co-chaired by Councilmembers Lisa Herbold and Lorena Gonzalez, with an assist from substitute CM Kirsten Harris-Talley. –All “progressives” in good standing. Since the idea behind the Task Force was to raise money from big business to create more affordable housing, one would expect it be packed with business people and experts on affordable housing. That wasn’t what happened, though. Truer to its name than to its mission, the Task Force was dominated by ideologues (“progressives”) who wanted to get their hands on some revenue.

Who ARE these guys?

So who was on there to grab that cash with both hands and make a stash? Let’s take a look…

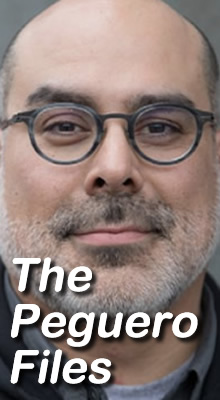

The SHARE organization was on the Task Force, in the person of homeless advocate Courtney O’Toole (pictured far right in the photo above, taken by the author). SHARE isn’t a housing provider; they’re a political pressure group that gets city money to keep people in “sanctioned” homeless camps. I have covered this group extensively on this blog. Two years ago, for example, I busted them for using a fake accountant to review their books. That man was fined, and SHARE was ultimately defunded by Seattle’s Human Services Department as a result. Unfortunately, SHARE’s funding was later restored at the insistence of Councilmember Kshama Sawant and Morrow’s other allies on the Council. SHARE stands to get a chunk of Head Tax money through its subsidiary LIHI (see the item on Tom Mathews below); it is therefore an interested party and shouldn’t have had anyone on the Task Force.

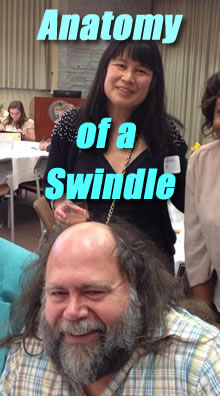

Through a Glass Darkly: Peggy Hotes and Scott Morrow, co-directors of the SHARE organization, keep a watchful eye on protege Courtney O’Toole as she represents SHARE’s interests on the Progressive Revenue Task Force. SHARE will be one of the prime beneficiaries of Head Tax proceeds, even though the homeless camps they run aren’t about getting people into “affordable housing.” Photo: David Preston

The Transit Riders Union was there, represented by Katie Wilson. Like SHARE, the Transit Riders Union is a pressure group that has nothing to do with housing. Or with transit riding either. Indeed, the group’s sole function seems to be demonstrating at City Hall in favor of more money for groups like SHARE and against removal of homeless camps. I don’t know how the Transit Riders Union gets funded, but if you follow the Head Tax money to its final destination, you’ll likely find some of it lining TRU’s pockets.

Katie Wilson of the Seattle Transit Riders Union defended the Head Tax at a raucous Ballard Town Hall in May. Wilson’s organization is politically allied with SHARE and other groups that stand to gain from the tax. Photo: David Preston

Lisa Daugaard was on the Task Force. Like the others, Daugaard has nothing to do with affordable housing. She works for the private Public Defender Association and runs a “social justice” project called L.E.A.D., which gets taxpayer money and which will get even more if the Head Tax is imposed on Seattle businesses. L.E.A.D. (Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion) is a politically sexy but non-evidence-based program that shields chronic drug users from arrest if they agree to engage with social workers and “accept” benefits. Daugaard is also one of the loudest voices behind heroin injection sites. You can see a video I made about the L.E.A.D. program’s impact in the Belltown neighborhood where it was piloted here.

Ian Eisenberg, owner of Uncle Ike’s Pot Shops, was there. I know Eisenberg and had hoped he’d be a voice for reason and for business on the Task Force. And he was a voice for business: His. Pot shops were exempted from the Head Tax under the proposal that Eisenberg helped craft. That’s a coincidence, I’m sure.

Ian “Uncle Ike” Eisenberg seemed bored at the January meeting of the Task Force. He got an exemption for pot shops out of his participation, though, so perhaps it was worth the sacrifice. Photo: David Preston

Tom Mathews, board member and former president of Walsh Construction was there. Mathews is the only member who could qualify as an expert on affordable housing.* But there’s a catch. Mathews is also on the board of the Low Income Housing Institute (LIHI), which I’ve also written about extensively on this blog. As this article shows, LIHI and Walsh Construction are cozy, which is understandable, since Walsh gets a good chunk of its business from LIHI projects. And here SHARE’s Scott Morrow comes into the picture again. Morrow co-founded LIHI in 1991 and LIHI and SHARE still cooperate, jointly running an archipelago of city-funded homeless encampments around town.

Although Tom Mathews represents a company that provides affordable housing, and therefore technically counts as a housing expert, his indirect connection with SHARE’s Scott Morrow makes his presence on the Task Force questionable. Morrow already had one representative on the Task Force (Courtney O’Toole), and since Mathews is also on the board of LIHI, which is effectively controlled by Morrow, it’s fair to say that SHARE was double-represented . . . or triple represented if you count SHARE’s other ally, Katie Wilson, of the Transit Riders Union. And let’s not forget that CMs Lisa Herbold and Kristen Harris-Tally, are long-time SHARE associates as well. All together, Morrow had at least five people on the Task Force representing his interests!

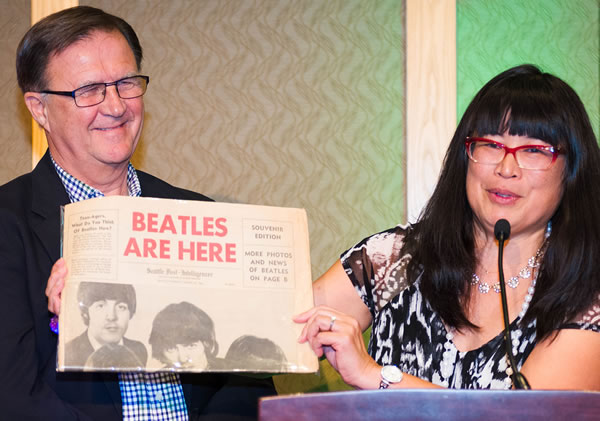

Tom Mathews of Walsh Construction poses with Sharon Lee of LIHI. Photo: Daily Journal of Commerce

And so it goes. There were 16 members on the Progressive Revenue Task Force, and if you look into it, you will probably find that every one of them had some stake in being there. They all had something to gain. They were all either activists, like Katie Wilson, or outright dependents, like Courtney O’Toole and Tom Mathews, or carpetbaggers, like Ian Eisenberg. There was only one housing provider (the double-agent Mathews) and there were no authentic representatives from any of the businesses that would have had to pay the tax. The few companies, like Bartell’s, who took the Council’s invitation seriously and applied to be on the Task Force were rejected. (See this Stranger article for more info on the also-rans.) Nor was business represented in the audience. The meeting I went to in January was packed with “social justice” advocates from SHARE the Transit Riders Union. Many of the people supporting the tax were familiar faces at Council meetings. There were no voices, besides my own, speaking against it.

Double Duty: Social justice advocate Sally Kinney testifies in favor of the Task Force’s original $150 million package at a meeting in January 2018. Kinney, who regularly speaks for SHARE’s interests at Council meetings, also serves on the City’s Community Involvement Commission. Photo: David Preston

Where was the Balance?

Why didn’t the Council try to bring balance to the Task Force? Maybe they didn’t see the lack of balance as a problem. Indeed, they might have seen a business-free Task Force as a selling point, since the premise of the tax seems to have been that big business is evil and has been shirking its duty to help out with the housing crisis. Given that premise, why would the Council listen to what business says on this?

Maybe the Council was in such a rush to push the Head Tax through that they didn’t want to risk bogging it down with dissonant voices. Or maybe they just needed to pay back some political favors they owed to SHARE and the others, and they thought no one would bother to look closely at the Task Force’s composition anyway, or ask where the members’ real interests lay. But if that’s what they thought, they were wrong.

Oink! Councilmembers Lorena Gonzalez and Lisa Herbold co-chaired the Progressive Revenue Task Force. Herbold has long-standing ties to SHARE and LIHI, both of whom were represented on the Task Force and both of whom stand to gain from tax if it’s ultimately implemented. Photo: David Preston

In early May, the Task Force submitted to the Council its proposed ordinance calling for a $500/employee annual tax on businesses grossing over $10 million. The plan was estimated to generate $150 million in revenue. Initial support for that package was not strong, though, and after hundreds of businesses big and small came out publicly against it, and Amazon, a prime target of the tax, stopped construction on two large building projects downtown in protest, Mayor Jenny Durkan suggested that she might veto the bill.

On May 14, the Council voted 9 to 0 for a pared-down package, proposed by Durkan, that is estimated to generate $50 million with a tax of about $275 on businesses grossing over $20 million. It will affect nearly 600 employers in Seattle. That is, if it survives. The Head Tax, even in its diminished form, has generated a surprising amount of controversy. And opposition. A referendum petition is being circulated by a group called “No Tax on Jobs” (FB: NoTaxOnJobs) and it appears to be well on the way to getting the required 18,000 to force a public vote on the tax in November.**

–By David Preston with assistance from Chad Smith

Do you appreciate what this blog does? There’s an easy way to say Thanks…

*Affordable housing is something a misnomer in the Seattle context. If, by affordable, we mean a rent-stabilized apartment pegged to a certain amount of Area Median Income (say 20%) then a city can guarantee to create a certain amount of affordable housing construction, subject only to the amount it can raise in taxes or bonding. But if, by affordable, we mean an apartment that can be built at market rate or significantly below, then Seattle is on a fool’s errand. The price-per-square-foot cost of government-built housing is known to run well above market rates.

**The author has participated in this effort as a volunteer signature gatherer.