Note ~ This article is a companion to a post on a wealthy Seattle man who said he appealed his property tax valuation because Seattle’s tax system was unfair to poor people. The article can be read as is, but to get the most out of it, refer back to the source here.

Is Paul right about Seattle’s tax being one of the lowest in the country? That depends on which income bracket you’re talking about. As you go up the scale to where Paul’s at, the lower the relative tax burden is. As you go down, it gets higher.

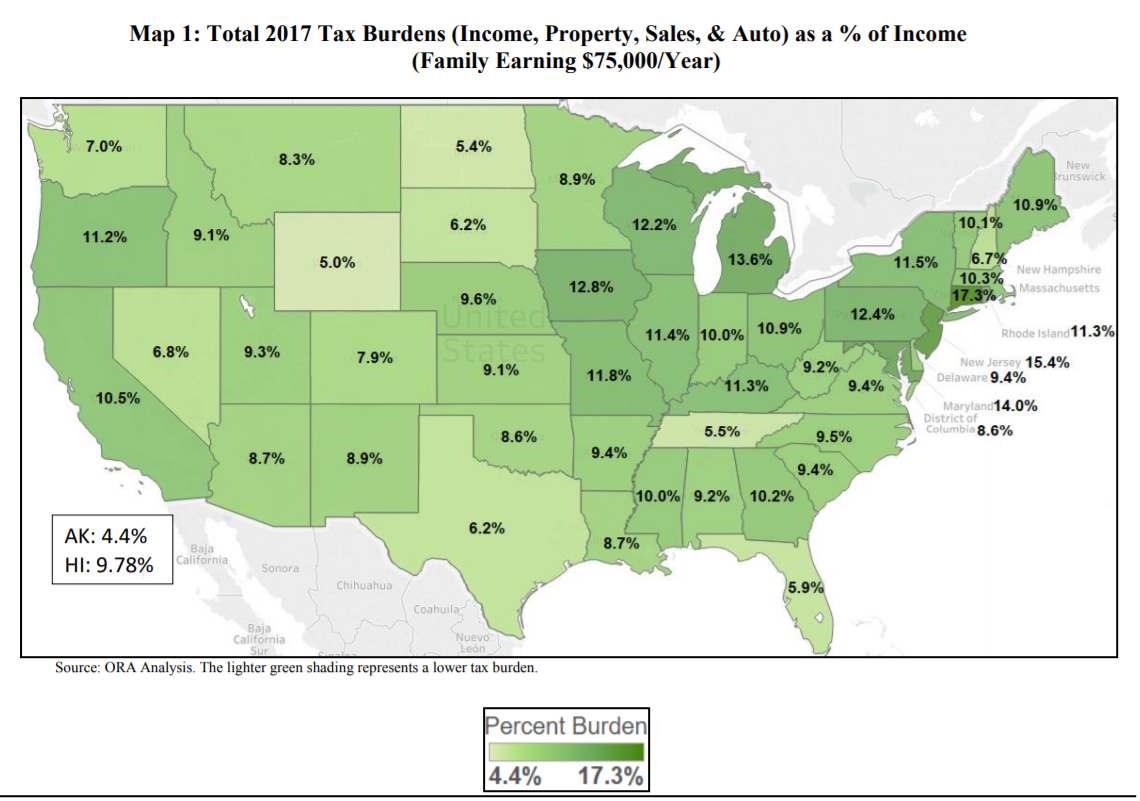

In 2018, the District of Columbia did an excellent comparative study on city and state tax rates around the country. The data is presented in easy to read charts and is broken out by several household income groups. The graphic below shows us a color-coded map of tax rates by state, where overall tax burden is based on a combination of four major taxes: income, property, sales, and auto. With an overall tax rate of 7%, Washington is 10th from the bottom. ▼

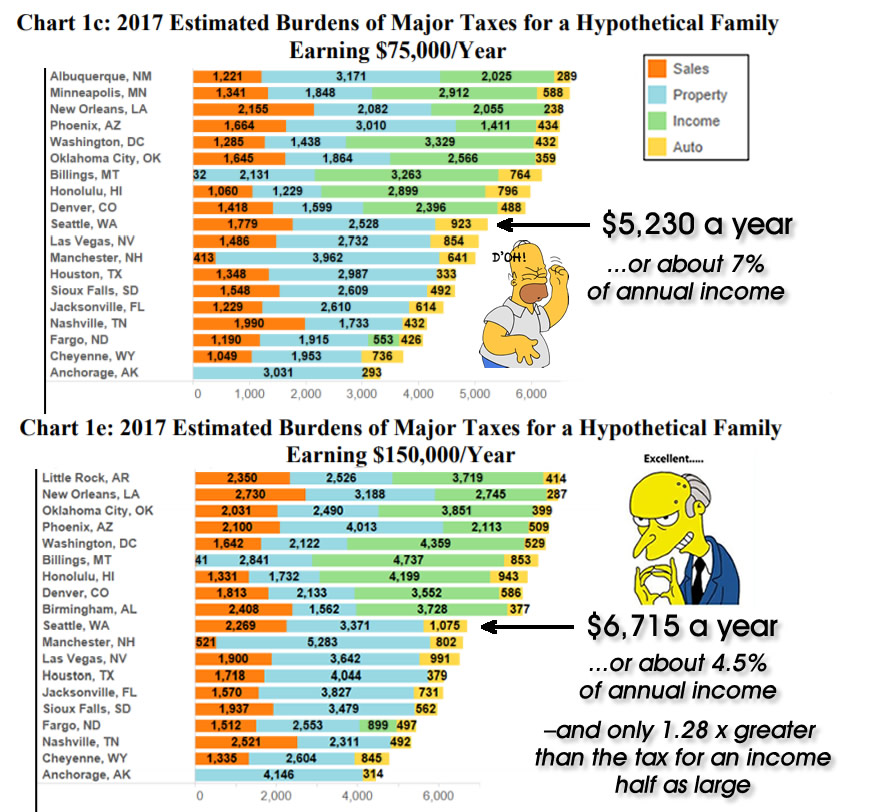

Here’s a city-by-city comparison of taxes for households at this same income level. As with Washington state, Seattle is also near the bottom. For a household earning $75,000 per year,* Seattle’s tax burden is $5,230, or about 7% of household income. ▼

▲ Note that there is no green segment in Seattle’s graph bar, which is true for 9 out of 10 of the low-tax cities. Seattle does not have an income tax. The other cities might have an income tax, but if so, it does not apply at this income level.

The Seattle City Council enacted an income tax in 2017, but it was overturned as a violation of the state’s constitution. Even if the tax had been upheld by the court, there would still be no green segment on the Seattle line, because the income tax would have applied only to incomes of above $250,000 for individuals and $500,000 for couples. At an estimated household income of $225,000, Paul’s family would be well below the cutoff.

How taxes affect the poor

The study authors assumed that people earning $75,000 and over live in their own homes and pay property tax, but what about people who rent? Renters pay property tax, too, but not in the form of a check to the tax assessor. Instead, their tax is factored into their rent bill. Every time the property tax goes up on a piece of rental property, the landlord either has to roll that cost increase into the next rent hike… or take a loss.**

The study authors made allowances for that, by factoring rent-based property tax into the tax burden using a multiplier they call the Property Tax Equivalent of Rent or PTER. (See Page 9 of the study.) Unfortunately, they do this only for their lowest 2017 income bracket of $25,000, which doesn’t account for the fact that, in a crowded and expensive city like Seattle, you often see people with much higher incomes living in apartments and still struggling to pay the rent. But the relative effect on tax burden still holds true.

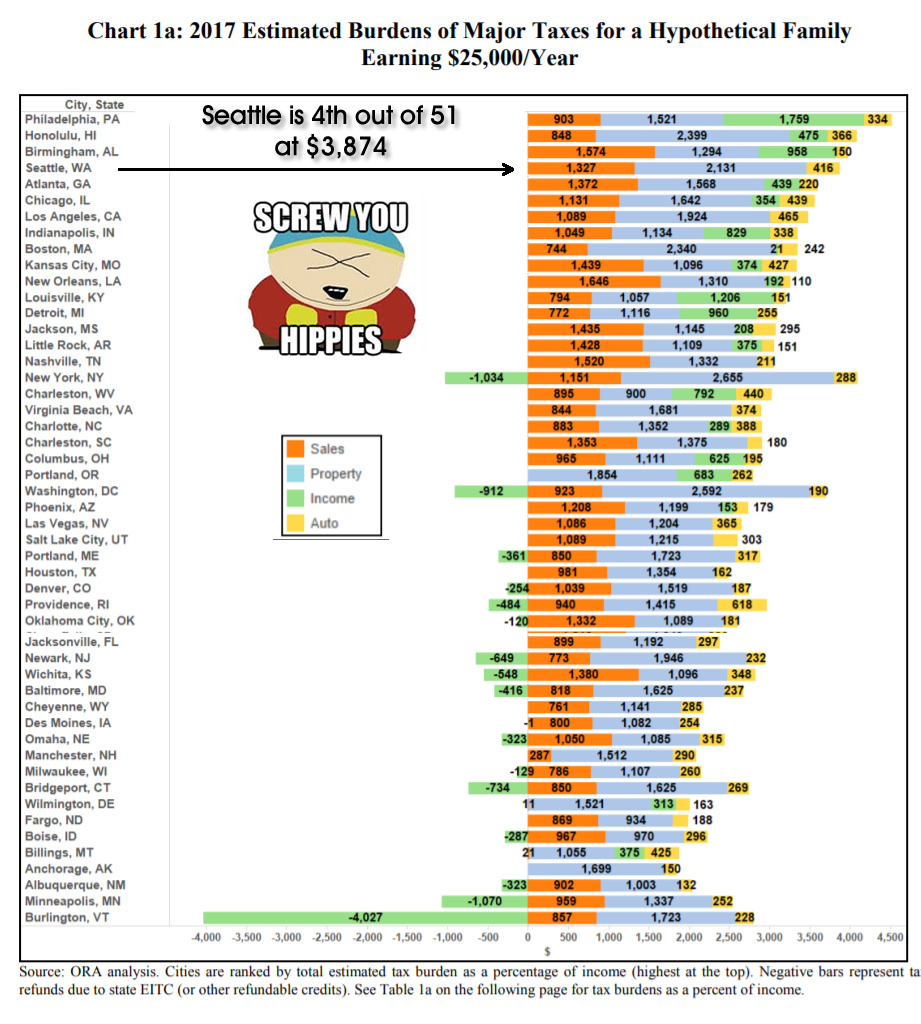

When you look at the tax burden on Seattleites in the lower income brackets, a very different picture of “tax burden” emerges. For people at the $25,000 income level – which in Seattle would be extreme poverty, even three years ago – we see that our city is actually one of the highest-tax cities in the nation. In fact, at $3,874 dollars a year, a person in this income range would be paying fully 15% of their income in taxes. And note that the biggest part of that figure is the Property Tax Equivalent of Rent, even though people at this level are assumed to not be paying property tax directly. ▼

The Rich Pay Less

As you go back up the income ladder, the tax bill rises in absolute terms, but it drops as a percentage of income and as a factor of the previous tax rate. Thus, the tax burden for a Seattle household making $150,000 a year is not twice as much as that for the family making $75,000, but just 1.28 times as much. ▼

So what about Paul?

But wait. Doesn’t this data support Paul’s claim that Seattle is a low-tax city? Yes and no. He’s right that it’s a low-tax city for people in his income bracket of $225,ooo, but it’s a high-tax city for those below the median annual income of $90,000, and as you get to the lowest income brackets, it’s an ultra-high-tax city. A punishingly high-tax city. And that’s because Seattle depends so heavily on taxes that hit the poor hardest, like its 10% sales tax (which is the same 10% whether you’re rich or poor) and a property tax that falls hardest on renters.

But wait. Doesn’t this data support Paul’s claim that Seattle is a low-tax city? Yes and no. He’s right that it’s a low-tax city for people in his income bracket of $225,ooo, but it’s a high-tax city for those below the median annual income of $90,000, and as you get to the lowest income brackets, it’s an ultra-high-tax city. A punishingly high-tax city. And that’s because Seattle depends so heavily on taxes that hit the poor hardest, like its 10% sales tax (which is the same 10% whether you’re rich or poor) and a property tax that falls hardest on renters.

And yes, it’s also because Seattle has no income tax, which would hit people harder in the pocketbook as they climb up the income ladder.

Will an income tax help, as Paul suggests? Maybe, but only if several conditions are true:

- The tax rate is raised beyond the city council’s current proposed amount 2.25% of income above the threshold, and…

- The income threshold is dropped from the current one of $250,000/$500,000 to a point where folks like Paul would have to pay it, and…

- Current property tax and sales taxes are lowered, and especially on the poor, assuming there’s a way to do that.

Item 3 is the most important, but it’s also least likely to happen. Given the Seattle city council’s record on spending and accountability, it’s more likely they would simply increase their spending (already at a whopping $6 billion) to soak up any new revenue an income tax brought in. Whenever a new tax measure is floated here, its always with the intent of funding some existing government service exists or one that’s planned. That was the case with the income tax, which was supposed to pay for more and better homeless services. The idea of tightening the city’s belt and passing the savings on to citizens is anathema to the council’s spendthrifts. The current income tax plan is not pegged to a direct decrease in property tax revenues; therefore, it will not equate to tax relief to Seattle’s poorest citizens.

As a veteran “urbanist” Paul is up on city budgets and relative tax burden. He knows that, as a wealthy person, he pays a much lower tax rate as a percentage of income than someone who makes half or a third as much as he does. Moreover, his implication that he would happily pay an income tax is hollow, since he knows that even if the city council’s proposed income tax had been upheld, he wouldn’t be paying a cent. Finally, he knows, or should know, the implications of what he did for the rest of us when he got a tax cut. As I point out in the main article, for every dollar a homeowner takes a dollar out of the tax till, a dollar must be put into it by someone else, and based on the demographics of Paul’s neighborhood, that means that the folks who have to make up for the taxes he doesn’t pay when he gets a property tax cut are most likely to be poor renters with incomes far lower than his own.

Does all that present our social justice hypocrite with a moral dilemma? Does it make him feel bad for what he’s done? What do you think?

–David Preston

Did you appreciate this article? Do you support honest journalism? Then please …