September 17, 2018 ~ Last week government officials announced they’d be bringing Seattle’s controversial LEAD drug abatement program to Burien, Washington. LEAD stands for Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion, and its stated purpose is to lower recidivism (habitual lawbreaking) by using police to “divert” drug offenders away from the courts and into stable housing, drug treatment programs, mental health counseling… and jobs. Whenever a cop arrests a drug user whom they think could be better served by a social worker than by a trip to jail, police can give them a choice: go to jail or get into LEAD. Once an offender is in the program, cops will go easier on them, as long as they’re meeting with their social worker regularly and not ratcheting up their criminal activity. The theory is that the person’s behavior will get better over time, even if they don’t get off drugs and become model citizens.

Started in Seattle in 2011, LEAD has generated gobs of positive media attention and around 40 copycat programs around the country. But for all the hoopla, LEAD hasn’t demonstrated better long-term drug addiction recovery rates than drug court or existing intervention programs. In fact, it hasn’t demonstrated much of anything. This article explains why.

Sloppy Science

Lisa Daugaard runs a non-profit organization (the Public Defenders Association) that gets money to run the LEAD program for King County. She’s also been involved in Seattle’s “police reform” process and is a critic of drug laws. These factors combine to create a conflict of interest issue that should have ruled her out of any involvement in the LEAD program.

Of all the claims made for it, the only actual result LEAD can demonstrate is a reduction in recidivism. But even that claim is questionable because of the way the pilot project and study were set up. The study purporting to show a decline in recidivism was not scientifically rigorous. It was not vetted by a human subjects review board, for example, and did not have tight controls over how the subjects interacted with each other or the researchers.

Social Desirability Bias

There’s a well-documented tendency of human study subjects to produce results they feel will be pleasing to the researchers. This is known as “social desirability bias.” In the case of LEAD, the most socially desirable result subjects could have produced would be a decrease in recidivism, because that’s the chief result the program was trying to produce. And that’s exactly the result the subjects did produce. A desired result is not necessarily an unscientific one; it depends on whether bias is controlled for (or limited) in the study design. In the case of LEAD, it wasn’t.

To ensure that any observed decline in recidivism was real and not the result of bias, the study authors would have needed to set it up so that once an arresting police officer referred a subject to LEAD, that officer would never again be in a position to decide to either arrest or not arrest that LEAD participant, or to influence any other officer in that regard. The participating officers would have had to be walled off from the non-participating officers somehow, and the non-participating officers would have to have been somehow “blinded” from knowing which drug users they saw on the streets were in the program and which weren’t, so they couldn’t give the LEAD participants preferential treatment when making arrests. (And the same goes, to a lesser extent, for prosecutors and judges, because they too might have had an biased impact on recidivism rates, albeit indirectly.*) If you’re a researcher, and you can’t wall the participants of a study off from each other so they don’t influence each other, and you can’t keep them from knowing and deliberately producing the result you’re looking for, then you haven’t got a rigorous, scientific study.

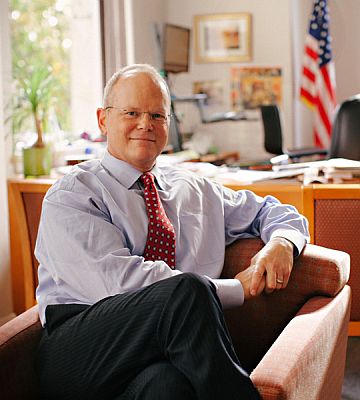

Brave New World: September 11, 2018. King County Executive Dow Constantine introduces the LEAD program to a group of press and citizens outside the police office in Burien., Washington. Image: King County

Were controls implemented to ensure that officers patrolling the streets of Seattle during the LEAD pilot project were unaware of which drug users they met on the streets were in the program, to prevent them from giving those drug users special treatment? No. And even if there had been such controls, it would have been impossible to keep the study’s other subjects, the drug users, from sharing that information with the police or with each other. What could researchers possibly have done to keep a street drug user from saying to an arresting officer, “Hey I’m in the LEAD program, so leave me alone or you’ll mess everything up.” What could they have done to keep the study subject officers from sharing that info with each other?

Officers participating in the LEAD pilot program gave drug users whom they knew were in the program a break and didn’t arrest them for minor crimes; that’s what they were supposed to do. That was part of the drug users’ reward for participating in the program. But non-participating officers almost certainly heard about the program as well. They might have found out which drug users were in the program, and they may have given them a break to help their buddies in the program, or to help the Police Department if they had the sense that that’s what was “desired.” Once word of the program got out, all cops might have given all drug users a break during the study period, deliberately not arresting them in order to lower recidivism and help the program succeed. Why would so many cops have wanted the program to succeed? I’ll discuss that below.

Other Confounding Factors

Some LEAD participants were apparently removed to other jurisdictions out of Seattle or King County. That means any arrests they picked up after being moved would no longer be trackable, at least if the tracking was limited to King County.

There are other ways in which the subjects could have been manipulated to provide the desired results. For example, drug users could have been given cash payments or other benefits they could then exchange for drugs, relieving them of the necessity to steal in order to support their habit. Just giving a drug user a monthly EBT card (food stamps) will usually result in a decline in criminal behavior, because now, instead of shoplifting or thieving to support his habit, the drug user can take his EBT card to the nearest crooked mini-mart, pawn it for fifty cents on the dollar, and get his fix for the next week or two. The only way to control for this as a factor would be to correlate decreased recidivism with an actual decline in drug use. Was that done for the study? –No. So how do we know users weren’t just getting paid to keep them from stealing to support their habit? –We don’t.

No waiting on Aisle 7: The LEAD Program in Burien comes with the assurance that anyone who wants drug treatment can now get it. Or so says King County Executive Dow Constantine. (See Press Conference document below.)

We also don’t know how much of the decline in recidivism was due to drug users being put indoors and out of sight. An important part of the LEAD program is to get drug users into housing. When you take an addict, put him indoors somewhere, and supply him with drugs, he is less likely to recidivate or attract the attention of police. But is he really any better off? Unfortunately, the LEAD program doesn’t address that question.

Conflict of Interest

The likelihood of patrol officers delivering a socially desirable drop in recidivism was increased substantially by the fact that police reformer (read: anti-cop activist) Lisa Daugaard was in charge of this project. Daugaard manages the Public Defender Association (PDA), which at one time contracted with the King County Prosecutor’s Office to provide free legal defense for indigent clients. Daugaard’s attitude to the justice system is complex, but the overall trend in her thinking is that the law is unfair to people of color and the poor. These days, her PDA is more of a lobbying group than anything, and it has supported such things as heroin injection sites and full-on legalization of narcotics. Daugaard was party to a lawsuit against the City of Seattle in which the plaintiffs, led by the ACLU, sought to enjoin the police from removing homeless camps on public land, unless it could guarantee all the camper a nice place to live. Going from her resume, it would be fair to call Daugaard a social justice warrior, if not an outright socialist.

Shortly before the LEAD program was created, Daugaard was a key player in a high-profile investigation of SPD by the Obama Justice Department. One spin-off of that was the Community Policing Commission (CPC), a brainchild of Daugaard’s. In the CPC, Daugaard envisioned a City-sponsored all-civilian group that would not only keep a watchful eye on police but would have right of review over decisions rendered by the City’s police disciplinary body, the Office of Professional Accountability, which Daugaard and others felt was tilted in the cops’ favor.

By the time LEAD was born, Daugaard was widely known among Seattle police as someone who had the power to hurt their careers if they displeased her, or to embarrass the SPD as organization.

With the Seattle Police Department in her pocket and the backing of other “progressives” at City Hall Daugaard was now in a position to build a project that could prove one of her pet theories, namely that enforcing drug laws was wrong and that we didn’t need to arrest drug users to get them to stop their problematic behavior. And the LEAD program was that project. The only problem with it was that it was so easy to game. Daugaard’s power over the police study subjects and her personal interest in the study outcome should have been a warning to the City and Daugaard’s academic collaborators at the University of Washington not to touch it. But this being Seattle – a town that lives and breaths social justice – no one batted an eye.

OK, but does it work?

Notwithstanding Daugaard’s role, does the LEAD program work? At all? In a word, no. Most Seattleites don’t care about concepts like lowering recidivism rates; they just want their neighborhoods to be free of drug crime and squalor. When they hear public officials singing LEAD’s praises they think, “Oh good. They’re finally doing something about all junkies on the street.” –But getting junkies off the street is not what LEAD does, and perhaps the most troubling thing about the program is that, for all the fanfare, it has not made a visible difference in drug-related crime even in the Belltown neighborhood where it was piloted and has been operating the longest, with the most money spent. As this video shows:

Look Out, Burien

Despite the fact that LEAD wasn’t successful in Seattle, the program is now being expanded around King County, with the intent of making it look like a success. Last week program director Daugaard stood with King County Executive Dow Constantine, King County Prosecutor Dan Satterberg, and other local officials and announced that the LEAD program would be comging to Burien and two other cities to be announced later, with $3.1 million in program funding to be divided among them. (Meanwhile, the program is being discontinued in the Skyway area of King County, though no reason was given for that.)

According to a talking points document sent by the County to Burien officials (see Press Conference, page 5) there is no longer a wait list to get into drug treatment or detox, either inpatient or outpatient. Frankly, this seems too good to be true. The document doesn’t make clear whether that applies just to LEAD participants or to everyone who wants treatment, but this language might have been inserted by lawyers who were worried that the County could be sued for discrimination if they gave preference to LEAD participants in providing County services.

King County Prosecutor Dan Satterberg says his office won’t be prosecuting drug possession under 1 gram from now on. Knowing they can’t be arrested or “diverted” from court by police, what motivation do drug users have to get into the LEAD program?

The program is evolving as it expands, and in some telling ways. At the press conference, Prosecutor Satterberg explained that his office will no longer be charging people who are arrested with less than a gram of narcotics on them, regardless of whether they’re in the LEAD program. Meanwhile, Burien City Manager Brian Wilson has said that police won’t even have to wait until they arrest someone to get them into the program now. And referrals will no longer be strictly related to drug use, because now police can refer someone based only on their suspicion that the person has committed a drug- or poverty-related crime. Or that they might commit such a crime at some point.

Wilson’s comments notwithstanding, there is some confusion within the LEAD program staff on whether an arrest must be used as a basis for referral (see Appendix).

As we see, eligibility for the program has expanded. In literature that was sent to Burien officials from the King County Executive, it was noted, at the bottom of page 2, that referrals no longer need come from just law enforcement but can also come from “community leaders” or even just “concerned individuals” – whatever that means. Practically speaking, anyone will now be able to refer a Burien resident to the LEAD program based solely on their judgment that the person appears to be homeless, mentally ill, or drug addicted. Or that they have committed (or might commit) crimes related to poverty. Is this Constitutional? Is it wise? –Inviting police, and even private citizens, to refer other citizens for a crime abatement program based on pure supposition? It sounds like a civil rights violation, like something the ACLU might challenge. But then, it’s not likely ACLU will be taking this one up, because they support Daugaard.

Burien LEAD Press Conference and Talking Points

LEAD_Program_in_Burien_Sept_Press_Conference_opt

Is LEAD still LEAD?

The new Burien version of LEAD is so different from the original as to not even be the same program. If anyone can refer a person to the LEAD program, that means the law enforcement basis of the program – the L and E of LEAD – is no longer there. Moreover, if Prosecutor Satterberg isn’t going to press charges for narcotics possession under a gram** then the D for Diversion is gone as well. Without the threat of arrest, there is now no motivation for someone who is referred to the program to accept it, since nothing will happen to them if they refuse.

Without the key components of law enforcement and diversion, we’re left wondering how the program can still even be called Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion. Why isn’t it just another government assistance program? It’s great that Burien’s getting some County money to help get needy people off the street and into treatment. But why does it need to come with all the bureaucratic strings attached? Burien already has a social services staff. Why not just give the 500,000 clams to the City of Burien and let them augment their existing assistance programs?

Can any of the officials at the podium answer me that? Or do they think we need another study?

–David Preston

* Supposedly the study considered only repeat arrests as recidivism, as opposed to repeat prosecutions or convictions.

**A gram is more than typical street drug user would have on them for personal use, based on an average total daily dose of 500 mg of a product untainted with Fentanyl. In practical terms, the one-gram threshold has been in place for a long time in King County. In fact it’s unusual for the Prosecutor’s office to file charges for anything less then three grams, and that usually happens only for repeat offenders who are arrested in connection with violent felonies. Recently, Satterberg has pushed to raise the threshold for charging to 10 grams or narcotics, which is an amount above what even most dealers on the street would possess.

Appendix

This e-mail exchange suggests that even LEAD program director Lisa Daugaard might be confused as to whether you have to commit a crime in order to be referred to the program.

Jen_Scaman_Lisa_Daugaard_Exchange

Do you value real investigative journalism? Then reward it!

well done dave

Very good analysis and exposure of what is really driving this program. Keep up the great work.