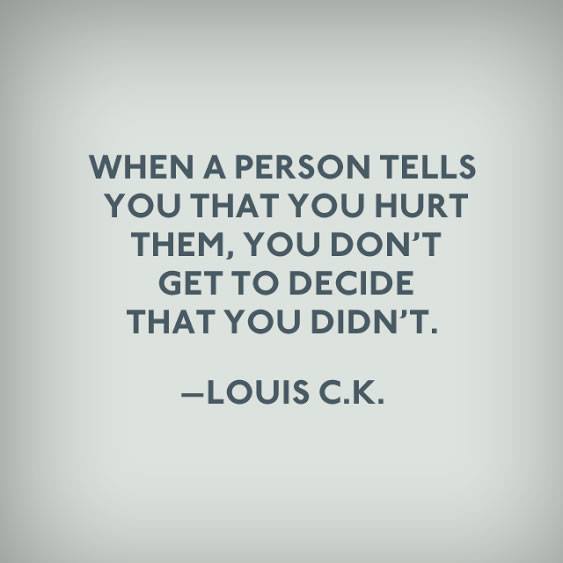

This soundbite by comedian/social critic Louis C. K. demonstrates the fallacy upon which many claims of harm have foundered. The reason the fallacy persists is because the basic idea has some truth in it. When a person tells you you’ve hurt them, you really don’t get to decide that they’ve not been hurt, because how would you know? By the same token, they don’t get to decide that YOU hurt them (as in, hurt them on purpose) because how would THEY know? That’s where the fallacy lies, in the confusion between action and intention.

Victim culture starts from the reasonable and demonstrable premise that people get hurt and proceeds to the false conclusion that, for every act of hurt, there must be someone who deliberately caused it. When a victim can’t find a specific individual to take the blame, he looks for an unspecific group or institution. Like a corporation, for example. Or maybe the whole capitalist system. Or modern technology. The government. Feminism. Slavery . . . The inducement to blame an institution for one’s hurt rises in proportion as the institution (a) has a proven record of misdeeds, or (b) has money with which to compensate victims, or (c) is simply unable to defend itself.

You can’t sue feminism, for example, so there’s no monetary inducement there. But neither can feminism rise to defend itself from your specific claims. Therefore, feminism makes a nice scapegoat for your various hurts, or your general dissatisfaction with life.

Corporations can defend themselves, so there’s some risk and hassle there. And the jackpot at the end of the rainbow is accordingly larger. Did someone (maybe you, maybe your server, who cares) bobble your coffee at the drive-up and scald you? McDonald’s doesn’t get to decide that you didn’t get scalded, do they? You’re injured, by God and someone’s gotta pay for that. McDonald’s can afford it, so why the hell not?

When someone tells me I’ve hurt them, I say, I’m sorry you’re hurt. –I acknowledge their feeling; I don’t dismiss it. But neither do I immediately accept the blame for it. Instead, I ask myself: What WAS my intention here? Should I have seen the hurt coming? Is there something I could’ve done to prevent it? –If it turns out that I am at fault, I apologize for my blunder, try to soothe the hurt, and move on. But if not, I don’t acknowledge that there is any fault to be assigned, and I don’t apologize. In my experience, apologizing for hurts I did not cause has never turned out well.

–David Preston