I recently asked the Seattle City Council to share with me any data they were looking at in their deliberations on the proposed minimum wage hike for Seattle. They sent me two studies, which I have linked for you below. The first study was prepared by the University of Washington specifically for the City Council:

University of Washington Minimum Wage Report

At 107 pages, it’s just a damn long report, and although it does contain a lot of info, it’s not well organized or explained. To help you along, I’ve highlighted some of the material that I consider most relevant.

The most important thing the UW report tells us is how many workers will be directly affected if the minimum wage is raised to $15 (102,000) and what businesses those people will be in (restaurants, retail, health care, warehouses).

The second study the Council used was prepared for them by three University of California-Berkeley wonks. It’s here:

UC Berkeley Minimum Wage Report

As with the UW report, I’ve highlighted some of the UCB report text you might want to pay special attention to.

The second report strongly suggests that a minimum wage hike in Seattle will not have a significant negative impact on business because similar wage hikes in San Francisco and San Jose did not have such an impact.

* * * * *

As the world knows by now, Seattle Mayor Ed Murray just announced his plan to raise the minimum wage to $15/hour. The raise will be staggered across different sized business and will be implemented in increments, with the last increment to be finished by 2021. See more on that story here:

Seattle Times: Mayor Murray’s Minimum Wage Plan Announced

In making his decision, the Mayor undoubtedly relied heavily on the UCB minimum wage impact report. That report argues – convincingly I think – that the San Francisco wage hike was good for workers without being bad for business.

Two grains of salt should be taken along with the UCB impact report. The first is that the report was prepared by people who almost certainly favor wage hikes. If you read the document closely, you’ll notice that the lead authors, Michael Reich and Dan Jacobs, cite their own research more often than they cite other studies. Collectively Reich and Jacobs have authored no fewer than seven research studies that they cite at various points in their impact paper. That’s what’s known as academic incest.

The second critique I would make of the UCB report is that the analogy it makes between Seattle and San Francisco may not be valid. San Francisco’s cost of living is considerably higher than Seattle’s (especially when rents are taken into consideration) yet San Francisco’s current minimum wage was just boosted to $10.55 per hour – much lower than the $15/hour wage that Seattle City Councilmember Kshama Sawant had originally proposed, and not much higher than Seattle’s current rate of $9.22/hour. That suggests that the cost of labor was already considerably more out-of-synch with the cost of living in San Francisco than it is here in Seattle. Accordingly, we would expect to see much less of a blip on the business radar after raising the wage modestly in spendy, trendy San Francisco than we would expect to see after raising it several dollars more in little old Seattle.

But this raises a broader question: How do we know what number the minimum wage should be be set at? If the implication of the UCB report is right and there’s no mischief in raising the minimum wage to $10/hour, why stop there? Or why stop at $15? Why not boost it to $25 and put everyone over the top?

Although the UCB authors don’t mention this fact, of course there is a point at which hiking the minimum wage number will start hurting the economy. Do the UCB authors know what the pain threshold is? No. They don’t. All they’ve demonstrated, really, was that San Francisco’s number ($10.55/hr as of 2014) was somewhere below the pain threshold. But how far below? Again, nobody knows.

And what about $15/hour for Seattle? Is that below the pain threshold or above it? Again, nobody knows. I guess we’ll find out as Mayor Murray’s plan is phased in. On the other hand, since the Murray plan is so gradual, it could be that Seattle’s small business is asphyxiated by imperceptible degrees.

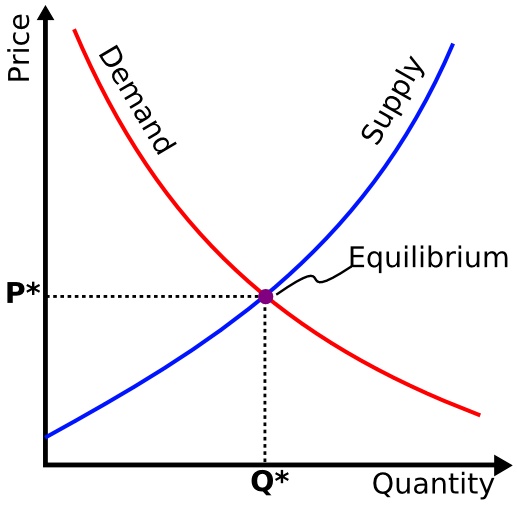

First, think of labor as a commodity, which it is. Then consider how that commodity would be priced if it were sold on a perfectly free and open market . . . with the understanding that there’s no such thing.

The chart below should be recognizable to anyone who’s had a high-school level economics class. It describes how the price is set for a given commodity. For example a widget . . . or an hour of unskilled labor.

Table 1. Setting a Natural Labor Price Point

If you’re a worker selling your labor, you must set the price for it at the “equilibrium” point where the lines of labor supply and labor demand intersect. If you ask for money than that, employers won’t buy your labor because they can get it somewhere else cheaper. If you set it below that point, you’re losing out.

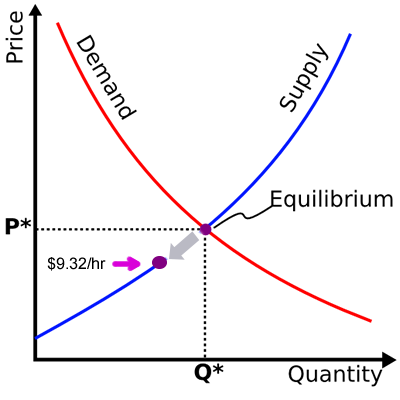

Now let’s assume that the current unskilled labor supply is priced artificially low for some reason. Let’s say it’s because Wal-Mart and Starbucks are colluding to keep wages down to the minimum. This means the price dot in the graph above (i.e., the wage rate) would be located somewhere below the imaginary equilibrium point. Like so:

Table 2. An Artificially Low Labor Price Point

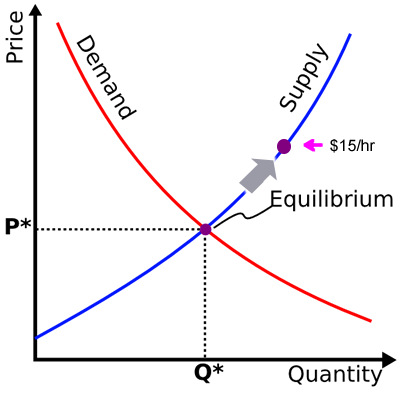

This means that you and other workers should be doing whatever you can (unionizing, striking, electing socialists) to raise that wage. Or you can just leave town, because if enough workers leave town and are not replaced by other workers (such as immigrants) the price for an hour of unskilled labor will come up naturally. But of course by then you’ll be gone. In any case, if the price of labor is artificially low, you can keep pushing it back up until you hit that natural equilibrium point without significantly disrupting business. But what happens if you raise the minimum wage to $15 and that number happens to be above the natural price point for an hour of labor? Like so:

Table 3: Artificially High Price Point

In that case, business will be affected and will have to do something to remain competitive and profitable. That action could take the form of:

–Raising prices

–Squeezing workers

–Leaving town

– ???

In the final analysis, I think Mayor Murray did the right thing. Seattle’s existing wage can probably stand a hike without hurting business, but that should be done gently and incrementally, and with the understanding that different sized businesses operate on very different profit margins when it comes to labor costs.

Will business be hurt by the time the wage raises to $15? Possibly. Consumers could be feeling some pain by then, too, as businesses phase in higher retail prices to compensate for increased labor costs. Some business owners will cope by cutting waste elsewhere in the supply chain, or by increasing labor productivity, as they did in San Francisco. (Better paid workers naturally make for more productive workers, according to the UC Berkeley study.)

Some businesses will probably go under, and the products and services they offer – along will the jobs they provided – will simply disappear. However, that’s a risk that Mayor Murray is apparently willing to take in exchange for the promise of a better standard of living for some 100,000 of Seattle’s workers.

~ fin ~

Coming up next: The informal economy. How will a new minimum wage affect it?