October 7, 2016

A hot mess gets hotter

In each of the past several years, ever greater numbers of homeless people have been camping out on publicly owned land in Seattle. Conditions around the encampment areas have steadily deteriorated, and in February of 2016, the situation reached a head when five people were shot (two fatally) in a no-man’s land area around downtown Seattle known as “the Jungle.” In response to the Jungle shooting, Mayor Ed Murray began stepping up removal of the camps. In August, the American Civil Liberties Union (the ACLU), worried about the campers’ rights, threatened a lawsuit. The ACLU and some self-styled progressives on the City Council then proposed a bill that, if passed, could effectively tie the Mayor’s hands. See the text of the bill here.

The chief provisions of the bill are that the City must give adequate warning and offer “outreach services” for 30 days to any group of five or more campers before evicting them. After the 30 days of outreach, the City still cannot remove campers unless it offers “adequate and accessible housing” to everyone affected.

A Poison Pill? The proposed ordinance doesn’t address the question of how much all these goodies are going to cost, but then, that’s probably a moot point anyway. If the true intent of the bill was to stop removals – as I suspect it was – then the more underfunded the proposal the better. If there’s no “adequate housing” for the homeless campers to move into – as indeed there won’t be – then they simply won’t have to go anywhere. They can stay in our parks and greenbelts forever. Any homeless campers who happen to find housing through the outreach programs will be replaced by others from somewhere else. Gradually, the parks will fill up with campers, and the quality of life of life in Seattle’s neighborhoods will continue to slip.

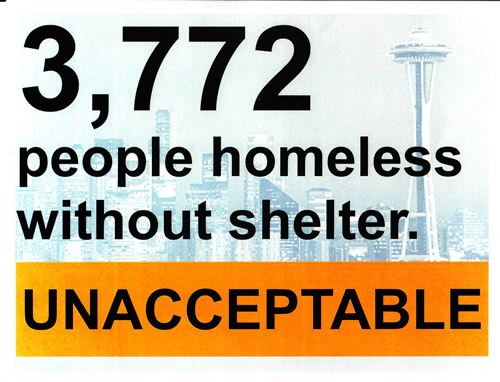

A homeless advocate handed this flyer to me at a public forum last year. The 3,772 number is based on the annual “one-night count” of people living on the street in King County. The number must be significantly higher by now.

Boom Towns When homeless camps are small, they tend to be unobtrusive. A few tents scattered about on a woody hillside generally don’t get in anyone’s way. But what about larger, semi-permanent clusters of tents? If the encampments bill passes as written, then many campers will naturally gather in groups to prevent themselves from being removed under the “five-or-more” rule.

A Star Is Born: As if by gravitational force, one tent attracts others to itself as a new camp arises near downtown Seattle. (Photo by Richard Paddon)

As a camp expands, it may acquire some communal resources such as furniture, cooking facilities, and gas-powered generators. Larger camps, being more visible, also act as magnets for donations from sympathetic neighbors. Many camps will eventually break apart for various reasons, but a few will continue growing and merging with other camps, to the point where they start to feel like a community. Before you know it, you’ve got a little town. This is the point at which the Constitutional problems come in.

Law of the Jungle Larger camps typically have entry barriers of some kind: a fence, a security guard, rules of admission . . . If you want to get into one of these larger camps, you’ll need to get permission. And maybe you’ll be denied. Or it could work this way: Maybe you’re already in the camp, and the camp boss or security staff decides that you’ve broken the rules. Or maybe they just don’t like the cut of your jib. Out you go! At that point, the other campers are assuming the role of property owners. In effect, they’re telling you to get off “their” land. You can argue with them, but you have no effective legal recourse, no appeal. The City has accepted their right to be there, and since they’re stronger than you, they get the last word.

This Google Map view shows the Nickelsville homeless camp as it looked in 2013. At its peak there were over 100 people living there. The camp was on public land (illegally) for over two and a half years, during which time access to the fenced-off site was strictly controlled by the camp boss and his cronies.

Some camps make people pay in order to stay there. A camp I toured recently charges people a fee for propane supplies and general use of the facilities. The fee is not exorbitant, but that’s not the point. Large or small, what the fee amounts to is a private party (the camp staff) charging other citizens a fee to use public land.

A Matter of Law

A Matter of Law

These practices violate the due process and equal protection clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which states:

No state [or any political subdivision] shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any state deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

Due Process In this context, “due process” means your right to NOT to be deprived of the use of public property without a trial or some other duly constituted administrative process. The government can legally bar you from public property – as they do when they “trespass” someone, for example – but only after they’ve given you your day in court.

Equal Protection Having equal protection of the laws means that you have exactly the same right to use the park as the camp boss and everyone else in camp. The government can’t deny you access to a public service or amenity for arbitrary reasons (race, creed, cut of your jib) so it goes without saying that another citizen couldn’t deny you access either.

Camp Second Chance sits on public land in southwest Seattle. The perimeter is fenced off and access to the camp is controlled through the security desk at front. (Photo by David Preston)

Setting up a semi-permanent homeless camp in a park or other public area is essentially a taking of land – not just from the campers who might be denied entry or kicked out but from the citizens as a whole. City governments may control public land, but it’s the people, collectively, who own it. By law, Seattle could not unilaterally sell or lease a city park without holding meetings and collecting citizen input first . . . yet ceding control of a greenbelt to a group of homeless people is doing just that: it’s converting public land to private use without a process. And that’s illegal.

Emergency Powers The ACLU and city council may try to justify these takings under some claim of extraordinary (read: extra-Constitutional) power pursuant to a civil emergency. In fact, both Mayor Murray and King County Executive Dow Constantine have already declared homelessness to be a public emergency, but these are administrative measures, without a general legal effect. Bonafide civil emergencies do occur, and governments do, understandably, assume extraordinary powers to cope with them. A mayor may declare martial law, for example, in the event of rioting or natural disaster. But such emergencies are, by definition, rare and relatively brief. Any suspension of rights needed to cope with them should be correspondingly brief as well. Homelessness, by contrast, is universal and chronic. As of now, it is not a general threat to the public order, but if it becomes known that there’s free land to be had in Seattle, that could change.

As we learned during the George W. Bush era, emergency powers are inherently dangerous to the rule of law. The ACLU should understand that better than anyone.

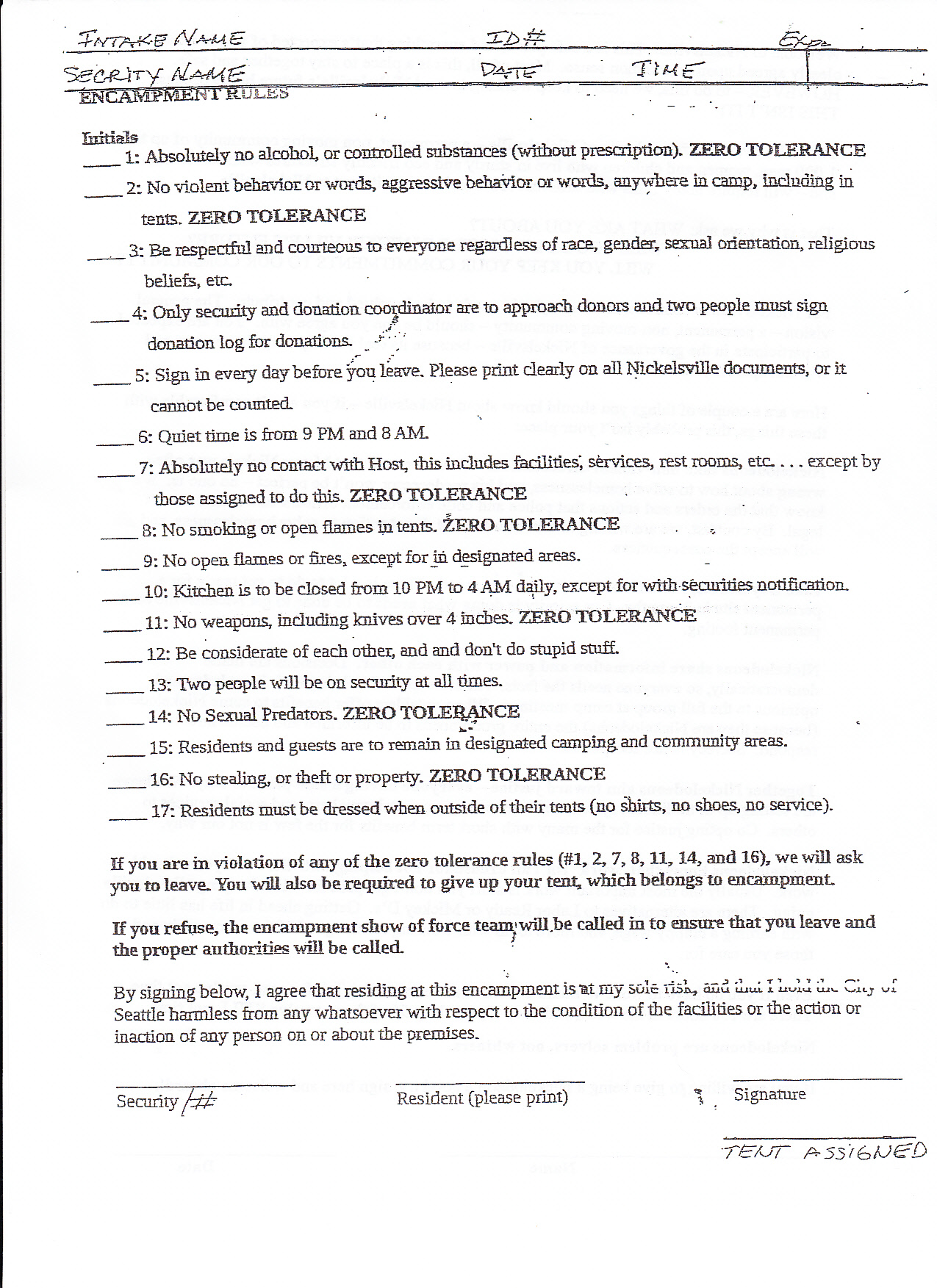

This list of rules was given me by a former Nickelsville resident. The camp boss and his lieutenants could use a violation of any one of them as a pretext on which to eject a resident. The police refused to enforce the boss’s eviction notices, but that didn’t matter, since he had plenty of other people to do it for him.

Where’s the actual harm?

In 2013, a large homeless camp that called itself Nickelsville was installed on public property about a mile from my house. This camp had many of the security features I described above, including a perimeter fence and not one but two guard shacks that were manned 24-7. Although the camp boosters (including some especially big fans at City Hall) claimed that the camp was “democratically run” and “self-governed,” it was in fact run with an iron fist by a local man and a group of his hand-picked lieutenants, some of whom did not live on the property. I volunteered in this camp, and I knew the “self-governed” story was just that, a story. The campers all knew it too, of course.

Inside looking out: This is the security booth at Camp Dearborn near downtown Seattle. The camp was not on public land, but it did block access to a nearby pocket park. It was the scene of two ugly camp rebellions, the second which ended with the camp’s eviction. (Photo by David Preston)

Nickelsville was subject to continual power struggles and the camp boss often had to frame-up and railroad his rivals to retain control. Since the boss had stacked the ruling council with his toadies, he could get generally away with this, but there were times when things got hairy. In March of 2012, the frame-up didn’t work, and the boss called in the police to eject the rebel campers. The cops wisely told him that they couldn’t act as his enforcers, since he didn’t have any more right to be on public land than they did. In desperation the boss removed the portable toilets from camp in order pressure the campers to oust the rebels, which they eventually did. (See the story here.) Following this episode, relations between the camp boss and police soured, and when the camp was finally evicted, the boss directed the campers to leave a mess for the city to clean up.

The same rebellion scenario played out at least three more times at other camps. The man runs a total of six such camps in the Seattle area, at least one of which is on public land at any given time. Over the years, hundreds of homeless men, women, and children have been evicted from public lands by this man and his cronies. Campers who have worked guard duty tell me that the boss keeps a blacklist of people who are not to be allowed into his camps, and that list is several pages long. Since the evictees and refuseniks are without any legal recourse to the boss’s decisions, their civil rights are being systematically violated.† Does the ACLU care about that? Does the City Council? I’m not seeing it.

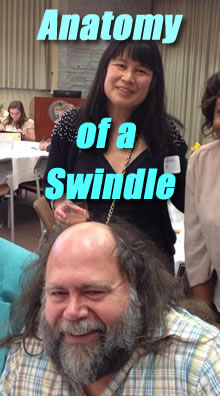

Scott Morrow (shown here with his chief lieutenant and girlfriend, Peggy Hotes) runs six homeless camps around Seattle. Morrow effectively controls the public land some of his camps occupy.

The power struggles at Nickelsville and other large camps are to some extent a reflection of the camp boss’s personality, but they are even more a function of the camp’s size. As camps grow, a fair and democratic process becomes harder to maintain. Power struggles and the depredations they entail are thus likely to become more common if the encampment bill is passed and the smaller camps (which will then be protected from eviction) expand and grow.

How can the ACLU be promoting this? Despite the ACLU’s reputation as a nest of legal eagles, in this case they don’t seem to have a basic grasp of the law . . . to say nothing of the dynamics of homeless camps. If they really cared about the homeless they’d doff their halos and get to work on building an effective appeal process for people living in boss-run camps and shelters.

The ACLU and city council envision an ever-expanding universe of individual liberties, liberties that we exercise with no harm to other individuals or to society as a whole. (So what if people want to live in the park? How does that hurt anyone?) However, this can be a risky assumption, as we see when we “run the tape forward” on the homeless camps bill. Or even when we just stop and look around ourselves in the present. In theory, this bill would protect the rights of the homeless without impinging on the rights of citizens to use their parks and public spaces. But in practice, it will make an already bad situation worse. Public land will be effectively taken from the public domain, and used for . . . what?

The ACLU and city council envision an ever-expanding universe of individual liberties, liberties that we exercise with no harm to other individuals or to society as a whole. (So what if people want to live in the park? How does that hurt anyone?) However, this can be a risky assumption, as we see when we “run the tape forward” on the homeless camps bill. Or even when we just stop and look around ourselves in the present. In theory, this bill would protect the rights of the homeless without impinging on the rights of citizens to use their parks and public spaces. But in practice, it will make an already bad situation worse. Public land will be effectively taken from the public domain, and used for . . . what?

Even if the bill weren’t an insult to the Constitution – which it is – it would still be a terrible idea.

-Essay by David Preston

† This man’s organization gets money from the city and county. Based on that, the City should take a much keener interest in what goes on in the camps. I have complained to the mayor and city council repeatedly about the camp’s disciplinary process. The only one to answer me was an assistant to councilmember Mike O’Brien, who said that the group’s “appeal process” is fair and that O’Brien saw no reason for the City to intervene. (See that response here.) Nor am I saying that camps (if they are allowed to exist at all) should be denied the right to have an enforce rules, since that could result in even greater mischief. What if a camp couldn’t eject a sex offender or someone who’s acting violent toward others? This conundrum only points up another problem with the City’s general “hands-off the homeless” approach.

I wrote Scott Morrow asking for information about the legal “tent encampment” in Ballard near Market Street and the illegal encampment by the Locks. In his reply, he stated that if residents of the legal encampment were found to be in contact with people in the illegal encampment, those residents would be warned and then–if they persisted– kicked out. I think he was trying to reassure me, but I was struck by the power he had and was quite willing to wield. I hate that illegal encampment. But TALKING to someone there gets you kicked out of the legal encampment? In America?

How does this hurt anybody? Needles, beer bottles and cans , humane waste, wet and dirty clothing and tarps are about as healthy for our parks and people as heart attacks. The main thing is the need for drug intervention and sanitary shelters and job creation to tackle an endless need for trash mitigation. Trash ends up in the sea. It ends up in the forests. Trash harms wildlife (a good example is the border where refugees and illegal aliens are attempting to cross ), no one benefits from allowing an anything goes attitude or so called freedom to create hazardous waste accumulation caused by humans. If I repeat myself so be it. Put people to work and our city would get cleaned and maintained .